I've never understood architecture. Like fine art, architecture seems like one of those subjects that requires years of training and study to be able to really, fully appreciate. But to plebes like myself, it remains a mysterious topic, out of reach and beyond my comprehension.

Despite my ignorance, there's something about Japanese architecture that stops me dead in my tracks. I don't always understand the history, engineering, theory, or artistry behind it all, but I'm always fascinated by Japanese architecture.

Obviously, I'm not the only one who's in love with Japanese architecture. For hundreds and hundreds of years, Japanese architects have received global recognition for their very distinctive work.

And as recently as just last month, Japan has captured the world's attention. This year, Japanese architect Toyo Ito was awarded architecture's greatest prize. Ito the sixth in a line of celebrated Japanese architects to win the Pritzker Prize, more than any other country except for the United States.

As I heard more and more about Japanese architects and spent hours scrolling through Google image searches, I began to wonder: why are Japanese architects so revered, so distinctive?

What separates the Frank Lloyd Wrights from the Toyo Itos of the world?

The Japanese Aesthetic

The Japanese aesthetic—the qualities that Japanese culture values in art—has always sort of been a mystery for the rest of the world. Westerners usually see it as yet another aspect of the mystical Orient they don't understand.

In reality though, the Japanese aesthetic makes a lot of sense. A lot of the Japanese aesthetic, like a lot of Japanese culture, has its roots in religion. Shinto and Buddhism are the two biggies in Japan, and once you understand that, it begins to click into place.

Shinto is a set of beliefs that puts a lot of emphasis on nature. Probably the thing that most people know about Shinto is that it believes that spirits, or kami, live in everything. That tree? He's got a little spirit inside it. Yeah, just like those Miyazaki movies you like so much.

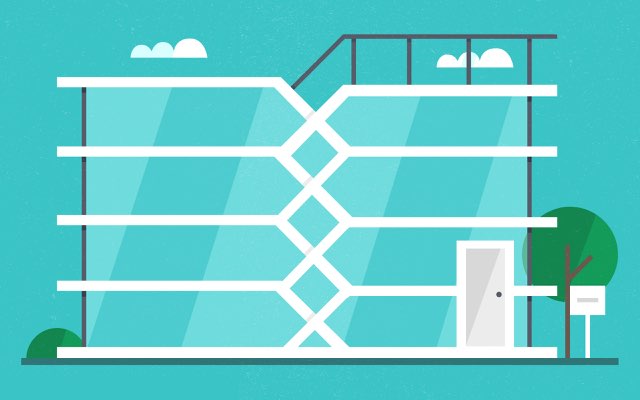

Ito has gotten a lot of attention in recent years in part because of his work on the Sendai Mediatheque, a library in Sendai. Located in the middle of the city that bore the brunt of the 3/11 earthquake, the Mediatheque came away from the disaster practically unscathed.

The Sendai Mediatheque is essentially a huge glass cube, which makes it look very, very fragile. If you looked at the Mediatheque and imagined one of the largest earthquakes in history hitting it, it wouldn't be hard to imagine the building shattering into pieces.

But the Mediatheque held steady. The structure of the building allowed it to brave the storm; or as one architecture critic put it: "The Mediatheque has these tubular-like things that look like trees, or look like waving grasses in the wind . . . They allowed the building to move with the earthquake and survive."

Like trees or grass. Ito's often says that some of his biggest inspirations are in nature — usually air, wind, and water. He doesn't explicitly talk about Shinto, but it's not so far-fetched to make that connection.

A lot of other architects use nature much more explicitly in their work. Another Pritzker winner, Ryue Nishizawa, created a very unique house in Tokyo aptly named Garden & House.

While the elements of nature aren't built directly into the structure of Garden & House, all of the flora lining the house make it leaps and bounds more attuned to nature than the concrete and brick buildings surrounding it.

Again, it's not that these buildings are explicitly Shinto shrines or anything, although many buildings — like the Tokyo Skytree — are blessed by Shinto clergy. But I think that this fusion of nature and architecture goes to show how deeply ingrained Shinto beliefs are into the Japanese aesthetic.

Zen and the Art of Japanese Architecture

Buddhism too has a role to play in shaping the Japanese aesthetic. A lot of Japanese Buddhist dogma, the kind of things that have made "Zen" a household word around the world, influences Japanese architecture.

Even if you're not a Buddhist scholar, you're still probably able to look at something and tell if it's very "Zen." You know the look—very spartan, simple, and even empty.

Those elements that are emphasized and valued in some forms Japanese Buddhism are written all over the Japanese aesthetic. They're especially easy to spot in places like rock gardens and other traditional locales.

Most Japanese rock gardens are raked and arranged to look like water or waves or some sort of movement. But a lot of gardens have just a lot of blank, flat space. Even though the trees and patterns often stand out a lot more, that blankness, that stillness, is just as crucial.

Lots of Japanese architects incorporate these elements in their own work. You'll see spaces with large, intentionally blank areas. It might look like the architect forgot or overlooked something, but it's usually deliberate.

I've noticed that Pritzker winner Tadao Ando is a big fan of big, blank spaces. In Ando's work, you'll see concrete walls stretching wide lengths and spanning great heights.

I've heard a lot of people complain about the immense amount of concrete used in works like this. I understand where those people are coming from; concrete is a boring, industrial material, and makes you think more of sidewalks than of a rock garden.

But I also understand Ando's intent. The dull surfaces make the more interesting features stand out and shine, the monotony can actually serve as a feature, rather than a nuisance.

Rejecting the Japanese Aesthetic

Simplicity. Beauty. Naturalism. These are elements of the Japanese aesthetic that you will see define Japanese architecture.

But then there are people who throw all of those concepts out the window, the people who understand the Japanese aesthetic so well that they intentionally choose to work around the fundamental principles that other architects follow so closely.

Somebody who definitely never won the Pritzker was an architect by the name of Arakawa. He and his partner, Madeline Gins, worked as artists and architects for over forty years, creating structures and places that will never, ever be honored by traditional architecture organizations.

You might have already seen one of their projects on TofuguTV — Yoro Park, the Site of Reversible Destiny. When traditional architects create a public park, they consider things like comfort, safety, and beauty.

Yoro Park doesn't.

Yoro Park is less of a public park and more of an excercise in creating the most outrageous, impractical space imaginable.

For Arakawa and Gins, Yoro Park was only one piece of their lifelong work. More recently, the duo condensed all of the features of Yoro Park into a single house.

Called the Bioscleave House, it cost millions to build, and is as much of a safety hazard as Yoro Park. Children are actually banned from entering the house, and adults must sign a waiver.

Everything in the Bioscleave House is mildly dangerous. The floors are bumpy and irregular, there are poles placed randomly throughout the house, and the whole house is painted in a variety of bright, disorienting colors.

Why all of the danger? A New York Times writer summarized Arakawa and Gin's philosophy nicely:

All of it is meant to keep the occupants on guard. Comfort, the thinking goes, is a precursor to death; the house is meant to lead its users into a perpetually "tentative" relationship with their surroundings, and thereby keep them young.

Extending your lifespan using dangerous architecture doesn't quite fit in with the Japanese aesthetic; I don't know of any Shinto or Buddhist teachings that advocate an adversarial relationship with your surroundings.

But there's space in Japanese architecture for both of these approaches. Unorthodox styles pushes the medium forward; the Japanese aesthetic anchors practices in tradition. But it's more than just looks.

If you’ve ever bought a house in the US, you know the normal considerations: How many bathrooms? How’s the location? Can you afford the price? And despite recent history, you probably still think it’s a better investment than paying rent to a landlord.

Jump across the Pacific, however, and you may be surprised at how differently the housing market works in Japan. Some of the differences are cool, like wacky promotions to attract buyers and crazy creative designs. But there’s also a dark side, if you care about the preservation of neighborhoods and the economic well-being of the average family.

Weird Home Promotions

When you buy a new house in the US, you don’t expect it to come with an extra prize like you get in a box of cereal. But one home-building company has offered buyers some odd perks. In one of their housing developments, the Izuyama company offered ten years of free burgers at their restaurant called Patty Cafe. If that sounds like it would get monotonous, the menu notes that they offer a variety of different sauces, such as demiglace, tomato cheese, salt, ponzu, wasabi mayo, and garlic, and from the photos, it looks much fancier than a fast-food joint.

There’s a catch, though: the deal only applies when the whole family shows up to dinner together – if even one person is missing, you have to pay. To the cynic, that might sound like a way to minimize the number of free burgers they have to give out, but the company says this rule is for the betterment of family life, because the number of Japanese families eating dinner together is decreasing. A survey showed that families eat together 46% of the time in Paris and 35% in Stockholm, but just 16% in Tokyo.

Another deal promoted another kind of togetherness: a free soba housewarming party for the neighbors, based on a custom from the Edo period of giving soba noodles to your new neighbors when you move in. "Soba 側"" (written with different kanji from the noodles) means “beside” or “nearby,” and noodles are long, so this tradition symbolizes the hope for a long and good relationship with the neighbors. The deal wasn’t just any soba, either: it was soba topped with gold leaf, which, aside from making the host look like a big spender, is supposed to bring good luck.

A different sort of deal was offered in a house with a fancy built-in sound system: the company would pay for ten years of a Sony online music streaming service that includes 20,000 songs. This house had recessed ceiling speakers even in the bath. Doors, windows, and even furniture was designed with sound quality in mind, as if they were building a concert hall. If you’re like me – the sort of person who puts your earbuds in when walking down the street in the hope that no one will talk to you – this one sounds like a way to keep people from interacting with others rather than encouraging it. But the company thinks otherwise: they say it promotes family spirit to listen to music together. And I guess they were thinking of harmony with the neighbors as well, since they used insulation and even window glass designed to dampen sound.

Solve a Puzzle, Win a Cheaper House

Okay, those bonuses are fun and all, but I think most of us would prefer a discount on price rather than a free housewarming party. One home-building company offered a deal like that, but only if you worked for it: you had to solve a sequence of online puzzles. There were three increasingly harder puzzles. Whoever solved the first one got a 1% discount, and for the second, a 3% discount was given. For the third one, 178 people solved the puzzle and one was chosen in a random drawing to get a 50% discount on the price of their house.

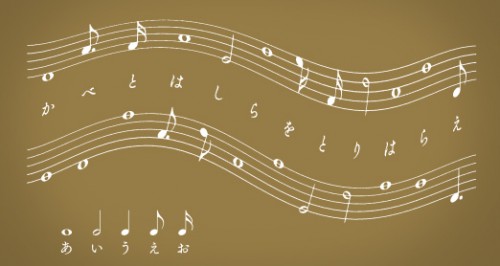

For an idea of what these puzzles were like, here’s the first and presumably the easiest. Not only would you never see a deal like this in the US, but if you did, the puzzle would have to be very different. Japan is still a country where everyone learns to read music in school. So it’s no stretch to ask people to look at the below and turn it into words:

The trick you have to know to start is that the Japanese version of “do-re-mi” for the notes in a scale is a-ka-sa-ta-na-ha-ma-ya-ra-wa. And at the bottom of that image is another trick: the Japanese vowels are matched to notes of different lengths. They also tell you to interpret the dot next to a note (which in actual music notation changes the length) as those two little dots you put next to a kana that turns a voiceless consonant to a voiced one, like ku to gu.

So, put all that together and translate the notes into Japanese syllables, and you read this as: sa-ka-n-be-re-ha-n-shi-ri-n-ra-gu:

Then, the lyrics above say “kabe to hashira wo toriharae,” which means “remove walls and polls.” That means, remove the syllables ka-be and ha-shi-ra, and you get the answer to the puzzle, sanrenringu, “trinity ring.”

Bravo to the winners, because I hate puzzles and I’m exhausted just typing out the explanation. But I guess for even just 1% off of the price of a brand new house it might be worth trying to figure it out.

Architect’s Heaven

If you’re looking for a house, maybe you’re jealous that you no one offers all-you-can-eat deals with it. But if you think you’re envious, the people who should really be jealous are American architects.

Japan is famous for unusual, new home architecture, unlike other countries where residential construction is not where architects usually get to be creative. The one I really want to live in this permanently Halloween apartment building.

The same architect who designed the Halloween apartments, also designed a shopping town that looks like a fairy-tale village – sadly no one gets to live there, but I’d take a job in one of those shops in a minute.

There’s also the house where all the walls are transparent…

The one with windows but no walls…

Or if you don’t care for that, you can have walls but no windows.

There’s also this tiny one-room seaside vacation home that’s basically one big window…

And this one that looks on the inside like it was designed by M.C Escher.

And if you’re looking for an awesome job market, you might want to become an architect in Japan: it’s the country with the most architects per capita in the world, with four times as many as the US. It’s also got twice as many construction jobs per capita as the US, despite the shrinking population low birth rate.

Disposable Homes

There’s an underlying thread that connects all these gimmicky contests and strange designs. Sadly, this thread is alarming and not nearly as much fun.

How can there be such a huge new home market when the Japanese population is getting smaller? Why is there so much competition that a company offers free food if you buy a home they’ve built? And what’s the deal with those crazy house designs? It’s all connected to the strangest thing about the Japanese housing market from an American perspective: there’s almost no market for existing homes.

Americans see a home as an investment. Despite some recent evidence to the contrary, the expectation is that a home will retain and maybe even increase in value. We see paying rent to a landlord as like flushing money down the toilet. But paying a mortgage payment to the bank is an investment in the future: the day will come when you can sell your house at a profit or hand it down as a valuable asset to your children.

But in Japan, a home is more like a car: It starts to decrease in value with age from the minute you buy it. Almost no one buys a “used” home to live in it. They just buy the property and tear down the existing house to build a new one. Half of Japanese homes are demolished within less than forty years, and no wonder, when one calculation says that they lose all their value by the time they’re thirty years old! The vast majority of people who buy a home are building a new house from scratch: 87% of Japan’s home sales are newly built houses, compared with only 11-34% in Western countries.

So that’s why there are so many construction jobs, and why companies compete for attention with clever promotions. And it’s also why architects can get away with those wacky designs. If you’ve ever owned a home in the US, you know that conventional wisdom cautions against doing unusual remodels, as they could hurt the resale value of your home. Potential buyers might run screaming from your purple bathroom tile. But in Japan, homes basically have no resale value. So you can build whatever crazy thing you want, secure in the depressing knowledge that it’s not going to make any difference to the zero value of the actual house when you go to sell the property.

The US real estate market joke is that the three most important things to consider when buying a house are “Location, location, location.” (Real estate agents are not the best comedians.) But apparently in Japan, those are ALL the things to consider, because that’s really all you’re buying.

The Dark Side

“So what?” you might say. “Lots of jobs in the building trade, lots of shiny new houses with purple bathroom tile, and sometimes a whole bunch of free burgers too!”

I’m not going to get into how and why the Japanese housing market came to be this way (read the references at the end for some analyses, if you like) but despite the fun stuff we started with, the dark side of this situation can’t be ignored.

It’s been argued that this system is terrible for the economic status of the Japanese middle class, compared to a place like the US where a home – the biggest purchase most people will ever make – retains or even gains some value. And the problem with trying to change the situation is that it’s self-perpetuating. Because a home isn’t a valuable asset, people don’t put a lot of money and effort into maintenance or renovations. No one in Japan spends their weekends at Home Depot buying stuff to fancy up their house. The result is that “used” homes are run down and out of fashion, so who would want to buy one? And that perpetuates the cycle.

There’s also a huge problem of abandoned houses. When homes can’t be sold, they may be left vacant and unmaintained. It costs a lot of money to tear a house down. On top of that, the tax system is a perverse counter-incentive: the property tax is six times higher if there’s no house on the lot. Basically, if you can’t sell your house (or rather, the land underneath it), you’d have to be crazy to tear it house down. The most recent statistics (from 2008, and the rates have been rising so it’s probably worse now) say that of 7.57 million vacant houses in Japan, one-third are abandoned. Having these abandoned houses around is terrible for a neighborhood – a fire risk, bad for property values, you name it.

As someone who loves old houses and old neighborhoods, I have to close by saying that another huge downside is the loss of character and history. Every time I visit my favorite Tokyo neighborhood, Yanaka, I see another old house being torn down and some ugly concrete box built in its place. I wonder how long the neighborhood can hold on to what makes it special. One long-time resident of the neighborhood told me that, when his neighbors tear down an old house in hopes of getting all the conveniences of modern living, it’s usually not as great as they expected.

The current state of housing in Japan is hurting the economy, the middle class, and the charm of and history of neighborhoods. With the exception of architects, everyone loses.