Some of you who have an interest in Japanese current affairs may know about what the current Liberal Democratic Party has put in place regarding Japan’s armed forces, which allows the right for a collective self defense (more on that later). These have attracted controversy from both within and outside of Japan. There have been large protests and even one person set himself on fire in Shinjuku to show his resolve against the changes. Worldwide media has also picked this up, with some people describing Prime Minister Abe’s “nationalism” (which I find accurate) and Japan’s “militarization” (which I don’t find accurate).

In short, I feel as though Japan is heading in a nationalist direction. But, it must be laid clear what this change means and what it does not. This idea of “militarization” also strikes me as very strange because it makes it sound as if Japan is Costa Rica without a professional army, which it already has. I'll try to explain the whole history, background and development of Japan’s military – and clarify some things about the current changes (or mess depending on your point of view) in Japan.

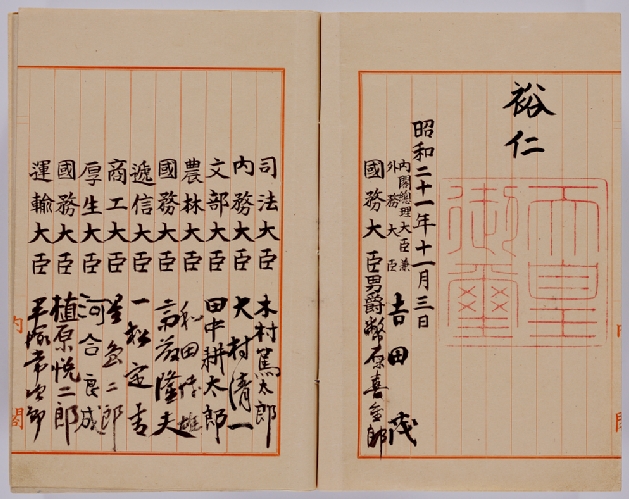

The Constitution

Firstly, all of the problems and controversies regarding the armed forces in Japan need to be taken in light of Article 9 of the Japanese postwar constitution (established 1947) – which states:

“ARTICLE 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. (2) To accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”

Nationalist groups say that the constitution is fundamentally not valid given how the constitution was “forced” on the Japanese people by the occupying/American forces but that’s an entirely different debate and mess. As you can see from the above, there is a problem with ambiguity.

Does the constitution prohibit all forms of armed forces and “war potential”? Or does it prohibit “war potential” only when it is used “as a means of settling international disputes”? And if so, where does one draw the lines between what conforms with such a condition and what does not?

These are ambiguities which have surfaced and resurfaced every time there’s a debate about the military in Japan. But the fact is that from the defeat of Japan things have changed massively. Aside from the legal debate which is perfectly open to interpretation, one has to look at how it has been interpreted and how that interpretation has changed.

History Timeline

I’ll make things easy and do a timeline-ish thing detailing the major events concerning the history of Japan.

1947 – Post-war (Showa) Constitution Adapted

- At this point Japan has no army and the constitution is interpreted as prohibiting one.

1950 – Start of Korean War

- Japan and the US start to get jittery on how Japan is virtually defenseless. Not only are there allied forces in Korea, but there was also the possibility of a communist victory on the Korean peninsula.

- Creation of the lightly armed National Police Reserve.

1954 – Promulgation of the Law of the Self Defense Forces

- National Police Reserve reorganized into the Japan Self Defense Forces (JSDF) with the Land Self-Defense Forces, Naval Self-Defense Forces and Air Self-Defense Forces clearly demarcated.

- Interpretation of Constitution: That self-defense actions and having a minimum force for this are legal but that, for example, the “right to join a war (kōsenken 交戦権) involving attacking an enemy is not”.

1959 – Sunakawa Incident

- Tokyo regional court rules that American forces on Japanese soil was illegal.

- Supreme Court of Japan overturns the decision saying that the 9th article of the constitution is applicable to Japanese forces but not to foreign (American) forces in Japan which have offensive capabilities. 1960 – Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan

- Basically, an amending of a treaty first signed in 1952. Both parties agree to help each other however Japan is not allowed to send forces to the US in the case of an attack due to article 9.

- Also allowed the US to place bases in Japan.

- Massive student and left-wing protests with more than 100 thousand surrounding parliament.

- Cabinet resigns to “take responsibility” but the treaty goes through.

1960s-1980s – The above set the tone for the next few decades as Japan and the Japanese government avoids contentious military issues and focuses on the economy. Some points to take note on:

- Japan has kept, with few exceptions, a cap on military spending at 1% of GDP per year.

- The principle adopted is the pretty much holding the minimum amount of power and using it at the lowest possible level to ensure Japan’s defense – It has also created and followed its set of “Three Non-Nuclear Principles” – Not making any, not having any, and not importing any. (American troops on Japanese soil are a different issue)

- As WWII draws even further away, the JSDF become more and more accepted.

1992 – Peacekeeping Operation Cooperation Law passed

- Law passed allowing the dispatch of the JSDF to peacekeeping / humanitarian operations after increasing questions about Japan’s contribution to the international community – JSDF dispatched to Cambodia in same year.

- Marks a clear departure from the only-in-Japan policy of the JSDF.

2001 – Invasion and Occupation of Afghanistan

- Naval JSDF dispatched to Indian Ocean to assist supply operations – the first deployment of the JSDF at a time of war (even though it was not directly involved in it).

2014 – Further change of Interpretation of Constitution

- Abe Cabinet changes interpretation to such that a “collective self defense” is allowed (explained later).

What Can We Say From This

A few clear and obvious patterns can be seen here:

-

In the beginning there were legal challenges regarding the very existence of the armed forces and the military was viewed extremely suspiciously by the public.

-

As time went on the status quo became more and more accepted. Firstly because memories of the war were dimming, but also perhaps because the JSDF was helping society through disaster relief, etc.

-

Legally, the boundaries of what the JSDF can do has been widened gradually, culminating in the current controversy.

What does the current change mean?

So what does this “collective self defense” mean then? Below is a video on the protests against the changes to the interpretation:

Before the current change, Japan considered coming to the aid of an ally an act which Japan had the right to do, but which would exceed the definition of “minimal use of force necessary for Japan’s defense”. In a more concrete fashion, if Japan were to be attacked by X country, America would have every right (and obligation) to come to Japan’s aid militarily. However, if America were to be attacked by X country, Japan would not be able to intervene militarily to aid America because that would be using Japan’s military force in an excessive way and not for the benefit of Japan’s defense.

The Abe cabinet has changed this interpretation to say that yes, it is within the “minimal use of force necessary for Japan’s defense” to send military forces in aid to an ally which has been attacked. In explanation, this is what the prime minister said in Parliament: (my translation)

“A condition for the use of the right to collective defense is that Japan, or a close ally of Japan, is attacked militarily. Furthermore, this must pose a danger to the Japanese people. The right to collective defense is a last resort, and shall be used with the minimum amount of force necessary […] The right to collective defense is, in the end, a means to protect the Japanese people and thus, it cannot be used to protect the citizenry of other countries even if our countries have close relations. Furthermore, we maintain our stance of exclusive defense (senshu boei) – pre-emptive strikes are not permitted.”

So if we are to believe his word (whether he is believable or not depends on the person) there are these criteria (which are certainly subjective and up to interpretation) which must be fulfilled before the right can be used.

So what does it not mean then?

What it does not mean, however, is that Japan would be able to attack a sovereign country by itself or launch an attack on another country in the name of self defense. Nor does it mean that Japan will be able to join another country in a preemptive strike, nor an invasion or another country. Supply support assisting other countries (as can be seen in the case of Afghanistan in 2001) seems to be perfectly fine though. But it does not mean a “rearming” of Japan because there haven’t been any clear reports of an increase in military spending – the limit of 1.0% of GDP seems to have been kept steady, so far.

Article 9 of the constitution still remains in effect and has not been repealed, even though the current prime minister would probably have done so if he could. Unfortunately for him, a change in the constitution requires a two-thirds majority in both the lower house of parliament (which he has), the upper house of parliament (which he does not), and a national referendum. And according to surveys, the public is both opposed to the current move toward allowing the right to collective defense, and certainly even more to the revision of article 9 as a whole.

So until that is changed, Japan’s military policy is legally restricted by the constitution even though, as we can see, that is liable to reinterpretation.

Japan's Current Military

But, there is one important thing that we haven’t discussed yet: the Japanese military itself. And, given how the current debate has been framed in the context of regional security fears, it is important to take a closer look at the Japanese military, the capabilities that it has, and what the public thinks about all of these things.

In terms of my own personal views? I’d say that saying Japan is “militarizing” is highly inaccurate – but for two very contradictory reasons.

First, the word militarizing makes it sound as if Japan is building up stockpiles of weaponry and conscripting people. It is not. Plus, its forces remain constrained in many ways.

Second, the word “militarizing” makes it sound as if Japan is currently a country with a weak military, and that Japan is now ditching its “unarmed ways.” This too is false. Unlike what many people think, Japan already has a very capable military force, thus it is already militarized.

It’s Not Militarizing: The GDP Argument

As I mentioned earlier, this move towards a “collective self-defense” has not come with a visible increase in the Japanese Defense expenditures. This has been kept at 1% of the GDP, just like it has been for a long, long time. What does 1% mean? Of course, it depends on several variables. Let’s take a look.

1% of a country’s GDP for military is actually really low when compared to other countries. Most spend much more. The CIA puts Japan’s military expenditure as a percentage of GDP at 103 in the world, at least in 2012.

Furthermore, this website states that the total number of active military personnel in Japan is around 247,000 people which is number 22 in the world. That still seems rather high, but when you consider it as a proportion of the total population (2.5 persons active in the military per 1000) the number is exceedingly low in the world.

Furthermore, one also has to take into account the type of military Japan possesses. The constitution prohibits the possession of force for purposes of attacking another country. So for example, Japan has a lot of fighter jets but no strategic bombers, etc.

It’s Not Militarizing: The “It Already Is Militarized” Argument

The other side of the coin is that people tend to underestimate the Japanese military and tend to think of Japan as not having a military presence. This is false for a few reasons.

While I did say that Japan does not have a strong offensive capability, a gun is a gun is a gun is a gun. And, to defend oneself militarily, one must shoot at someone else. The point is, while Japan may not have equipment that is explicitly offensive, there is quite a bit of crossover in terms of what is defensive and what is offensive. That is to say, it’s hard to pretend that Japan has zero offensive capability. A lot of what they have for defense can easily become offensive as well.

Secondly, while it is clear that Japan does not spend much and has way fewer people in the military for a country of its size, this does not mean that in absolute terms the Japanese military is not sizable. As noted above, it is, in terms of active personnel, #22 in the entire world. Sizable, but nothing that big and certainly smaller than its neighbors China, North Korea, and South Korea, which are first, fifth, and sixth in the world respectively.

However, 1.0% of the third largest economic power in the world is very clearly a sizable amount. Japan, as of 2013, spends around $50 billion USD on its military each year – roughly 50% more than what South Korea spends. In addition, Japan has the 7th or 8th largest military budget in the world depending on the source. With the above, it is clear that Japan has a sizable, modern and professional military.

Thirdly, one must also note the sizable number of American forces (38,000 according to the United Forces Japan website) stationed in Japan which certainly hold sizable offensive capabilities. Most of the time, these are stationed in out-of-sight, out-of-mind locations (unless you’re living in Okinawa). However, just one hour from Shinjuku, and entirely within Tokyo prefecture, is Yokota airbase in Fussa city. Similarly, an hour from Yokohama is Yokosuka naval base.

This also means that even if they are not Japanese, Japan has signficant forces stationed on its soil which can use Japan as a staging area in the case of a military conflict. And while Prime Minister Abe says that the US needs Japanese consent for any deployment, the US has already historically used Japan as a basing ground in the Korean war and the Vietnam war.

So What do the Japanese think of their own Military anyway?

Now let’s take a look at public perception? I’ll be addressing the arguments about the constitution etc. in the next part but I’m going to focus on the perceptions of the military here now.

1) The Japanese public has gradually come to accept the defense forces as a being normal.

As you can imagine, Japan after World War II was heavily traumatized, and many blamed the military for the mess that Japan found itself in. This is why especially in the immediate decades after the war, the military was treated with heavy suspicion. In contrast to that, a survey by the Japanese government released in 2012 states that 91.7% of the Japanese population have a positive impression of the JSDF.

That has changed gradually as fears that of Japan being dragged into another conflict were realized. Up until now, no Japanese self-defense forces had been involved in any armed fighting – at most it was involved in back-end support and/or peace keeping operations overseas.

In addition to this, the Self-Defense Forces also play an important role internally in terms of disaster management. The Self-Defense Forces were deployed to Tohoku after the earthquake / tsunami disaster of 2011 and in that sense, they clearly do play at least some positive role within Japan. It is because of all this that the JSDF has become a gradually accepted part of the nation of Japan.

2) The Japanese public heavily underestimates the strength of their own forces.

This article provides a very good explanation of this – most of the Japanese population (actually I think it’s fair to say most of the world population) views Japan as without a “true” standing army with minimal defenses.

To the typical Japanese person, the JSDF is not an “army” – it is a “self-defence force” and nothing more. And as the article above notes, this underestimation may be a reason for why the Japanese are sometimes bewildered by their neighbours’ complaints about its military power.

3) The self defense forces are not exactly prestigious

As a reflection of the above, the JSDF isn’t exactly prestigious – Japan does not make movies like Black Hawk Down or Saving Private Ryan. And while being in the Marines in the US is highly respected and military service considered to be “service to the nation”, there is no equivalent that I know of in Japan.

Wikipedia has a nice write-up about this. Basically, according to the article, the JSDF gets its recruits from poorer rural areas and top university graduates tend to stay the hell away. No doubt the Japanese do thank the JSDF members for their service – it just isn’t as venerated as in some other countries.

All that being said…

So I’ve taken a look at Japan’s military strength and this idea of “Militarization” that’s floating around. The point is that, in my view, there’s a lot of overestimation going on. This includes current changes and Japan’s actual military strength, which is nothing to scoff at.

Now that you know about the Japanese military and what it has, we will be looking at “who is saying what” about militarization, Article 9, the arguments for and against the Japanese military, as well as some deeper analysis around what people are actually saying about the current changes instituted by the Abe cabinet.

What's With All the Arguing?

Now we'll take a look at who is saying what in terms of the debate: about the constitution, the army, and the recent changes themselves.

I can’t possibly cover every single point of view so I’ll talk about the most common ones, get nice quotes if I can find them, and explain what I think about them. In any case, I hope that this will help inform you about this very important part of Japan’s policy – a policy that people don’t like to talk about but may (in the worst case) affect Japan’s future.

The Constitution – In Particular Article 9

“Article 9 was forced on Japan by America to gut it and keep it weak!”

And therefore, “we need to get rid of it so that Japan can resume being a normal strong country!”

Found on: Internet forums. Facebook comments. Not openly stated by mainstream politicians but some nationalist ones are certainly thinking it.

What I think: How much of the Japanese constitution is Made-in-America is a whole other debate that I’m not going to go into. However this bang-the-pots nationalism doesn’t really make sense to me because of two reasons.

Firstly, the constitution may have been written largely by the Americans, however the Japanese public has accepted article 9 and even until now, most polls show a majority against the revision of the article 9 (all links in Japanese). The sweeping claim that America has forced Japan into something it doesn’t want rings hollow when you consider this.

Secondly, it’s not as if Japan hasn’t gained from Article 9. After all, Article 9 pairs with America assuming of responsibility for Japan’s defense. Think about it – some countries would probably love to dump the need to have their own full army and receive the protection of the biggest military power on Earth. So Japan has benefited indirectly from the implications of Article 9.

On the other hand …

“Article 9 keeps us peaceful”

“Today marks 60 years from when the Japan Self Defense Forces were formed. Not a single serviceman has been killed, and we have not killed a single foreign person. This kind of army is exceedingly rare among the main countries in the world – and this is because of the principle of not allowing force to be used overseas, under this Constitution, and because of Article 9. Article 9 has protected the lives of our soldiers. Don’t you dare break this treasure!”

Japan Communist Party representative Shii Kazuo on Twitter.

Usually said by: left-of-center groups. The majority of citizenry, which is opposed to a change in the constitution, also probably agrees with this.

What I think: This is certainly expressed often – but how Article 9 actually prevents Japan entering into war isn’t actually explained as often. Certainly, as a law it does constrain the government from having any too glaringly offensive armed forces. And while there is ample room for interpreting the constitution, especially given the historical interpretations, perhaps there is a limit before it becomes absurd and clearly unconstitutional.

But then…

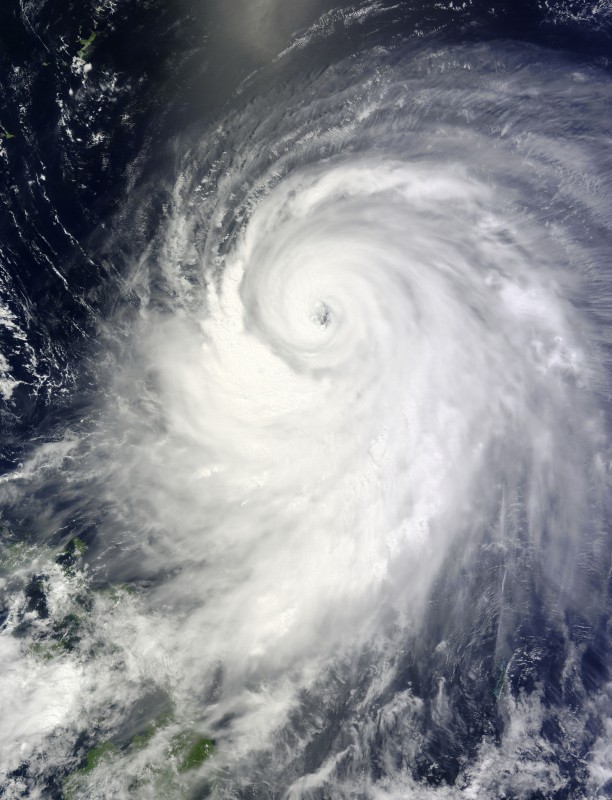

“If peace was as simple as making a law for it, Japan might as well enact an anti-Typhoon law.”

After all, we just need a law against it right?

As mentioned by a friend of mine. And I don’t think anyone really disagrees with this.

The point is that war and peace are issues with political, economic and diplomatic dimensions – having a provision in the constitution prohibiting it alone certainly isn’t enough. This point of view doesn’t really view Article 9 as good or bad, but ineffective and at most symbolic.

But even so, perhaps symbols are useful anyway? Perhaps having a symbol, no matter how ineffectual, is better than not having one?

On Japan’s Military

Moving away from legal arguments, we come to debates about Japan’s military, what role they should play, how much should the government spends on them, etc.

“Japan needs to have a strong(er) military to defend itself given rising regional tensions”

Since…

“The security environment surrounding Japan has become increasingly severe, being encompassed by various challenges and destabilizing factors, which are becoming more tangible and acute.”

–As stated by Japan Defense White Paper, 2014

Versus.

“A strong(er) military itself provokes rising regional tensions”

Example: Chinese protests reported by CNN

What I think: Very chicken and egg / vicious cycle thing here but both are true to an extent. Regional tensions are rising and North Korea seems to have a good time firing missiles into the Sea of Japan.

On the other hand China and South Korea often protest against Japan when Japan makes moves to strengthen its military. There is something to be said for how both countries are using Japan as a political punching bag for domestic agendas. But then again, it’s not as if Japan couldn’t predict the above. So is Japan just trying to defend itself or adding fuel into the fire?

“Japan, being an economic and significant power needs to fulfill it’s military responsibilities”

Example:

“Japan’s reliance on the United States for protection undermines Japanese credibility in the world. It projects the image of an economically strong country that is unable to defend itself … There is also the issue of the fundamental unfairness of the alliance to the American people. Should America be compelled to defend Japan for an indefinite period without reciprocity?”

What I think: This has been increasingly noted from the US in recent years, but then again it suits Japanese nationalists – who want to see a “Strong / Normal Japan” – perfectly well too.

Note that until 1991, Japan’s forces never participated in any peacekeeping operations. Not to mention that before the current change in the constitutional interpretation, the US would be obligated to come to Japan’s aid in the event of war, but not the other way around. Some would say that Japan, as the previous second and current third largest economy of the world, ought to pull their weight – after all, it’s not as if they can’t.

Detractors, however, say that while it all sounds nice, this is a recipe for Japan to get dragged into unnecessary conflicts – not entirely unfounded when we consider the bungling of some peacekeeping missions in history.

But then,

“Japan really doesn’t need the economic burden of a military”.

What I think: I’ve noted earlier, Japan spends only 1% of its GDP on defense, a rate which puts it near the bottom of the world rankings. I’ve also written elsewhere that Japan’s government is essentially broke – and really doesn’t need anything else on its plate to spend yen on.

So having a stronger military simply means a choice between three painful options: more debt, higher taxes, or less spending elsewhere – pacifists would add that military spending doesn’t actually improve the welfare of the Japanese people anyway. But of course, military spending is a very “contingency situation” thing – how much military spending is “adequate”? Does Japan want to run the risk of not being prepared in the case of a conflict? How high are the chances of such a conflict anyway?

About The US Army In Japan

“We need’em”

As per official government policy.

“But not in our neighborhood”

As stated by…

What I think: The US army doesn’t have a good rep in Japan, especially in Okinawa. One incident often remembered about it is the rape of a twelve year Okinawan girl by three US servicemen in 1995. Not to mention that the Japanese government does sponsor heavily the upkeep of bases in Japan (this is within the Japanese defense budget).

The crime point is to some extent overblown because the crime rate of US servicemen is lower than the general Japanese population. But nonetheless, the central government views the US forces as something that is welcome and which contributes to Japan’s defense. It’s just that on the local level no one really wants to have them on their soil.

About the Right to Collective Defense

As in Picture,”The Right to Collective Defense = War!”

“If we allow the right to collective self-defense, in the case that a certain country declares that they are being attacked, it is possible that Japan will mobilize its forces and use military force overseas, following mobilizing US forces […] We cannot just let this move, which will allow our children to be sent to the battlefield, pass.” – Petition on Change.org

Versus

“If having this right is a right-wing plot, then all other countries in the world are ruled by fascists”

…A comment I saw on Blogos, a Japanese political blog collation site.

What I think: Japan gains pretty much nothing concrete from reinterpreting the constitution except for avoiding being called a leech. PM Abe says that a condition for the use of the right includes reasonable damage to the Japanese people’s welfare, but in essence what Japan gains is the ability to use its own military to defend someone else! Yay!

The US is happy with this, but why would Japan make such a reinterpretation in the first place? On a very common sense level, it is kind of absurd that you are in an alliance with someone and that you can’t help your ally in a time of war. However, on a political level, reinterpreting the law allows for more flexibility to use the JSDF forces. Ideology-wise, it also is a step towards the “normalization” of Japan as a country with normal military capabilities.

And this is true. The right to collective defense is “normal” in the world. Pretty much only Japan and Switzerland did not recognize its right to a collective self defense. Now Switzerland is hanging out alone in that party.

The counter point is that it is a right that Japan can live without. After all – if it is simply the right to fight for someone else, then Japan doesn’t need it in the least. And – as repeated for the umpteenth time – this may lead to Japan getting sucked into a conflict.

So After All The Arguing…

All in all the public opinion appears to be 1) In favor of retaining Article 9, 2) Conflicted over the US army especially if they end up in their local neighborhood and 3) Opposed to the current reinterpretation (though this varies by survey). However, the ruling party is more conservative and nationalist than the general public opinion. And as can be seen from the current changes, it is also open to ignoring the public at times.

Nonetheless, the question still remains: Are we seeing a Japan that is moving towards war or one which is simply trying to ensure its own security? Is it possibly both at the same time? No simple answers here, but in the meantime you can be sure that there will be a lot of arguing about it, both in and outside Japan.