This is a story about you.

Three years ago, you began to feel restless. Not "time to take up a new hobby" restless, but more like "time to travel the world and have exciting, new experiences" restless.

So you came up with a plan. An incredible, ridiculous plan. You decided to move to Japan… and live in the wilderness1.

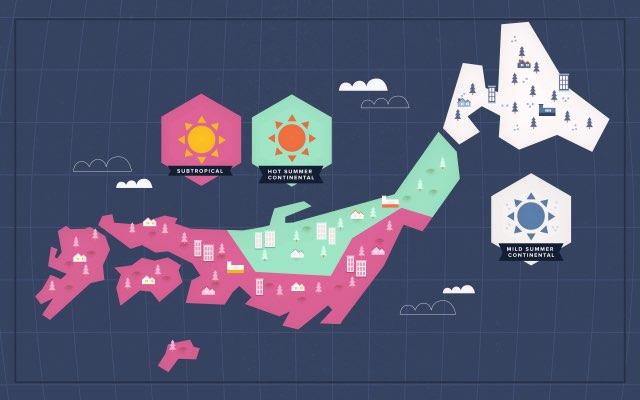

After some research, you discovered that Japan can be divided into three broad climatic zones: mild-summer continental (Hokkaido), hot-summer continental (northeast Honshu), and subtropical (central/southern Japan).

You wanted to fully experience each of these regions, so you planned out a three-year survival trip, with one year devoted to each climate. That way, you'd get to observe all four seasons in each region, and have lots of time to explore the land.

You packed up your survival gear and headed to Japan. Somehow, you obtained legal clearance for your survival adventure (maybe they thought you were joking?). You plunged into the forest, leaving the towering skyscrapers and bright lights of civilization behind.

As the months passed, you took regular notes in order to pass your experiences on to an enraptured future audience. What audience? Why, the fine readers of Tofugu, of course!

Now that future has come. It's time to relate your adventure.

Overall Impressions

Many of the experiences you had during your adventure were distinct to each of the three climate regions, while others were common across Japan. Let's start by going over what seemed to be constant throughout the three.

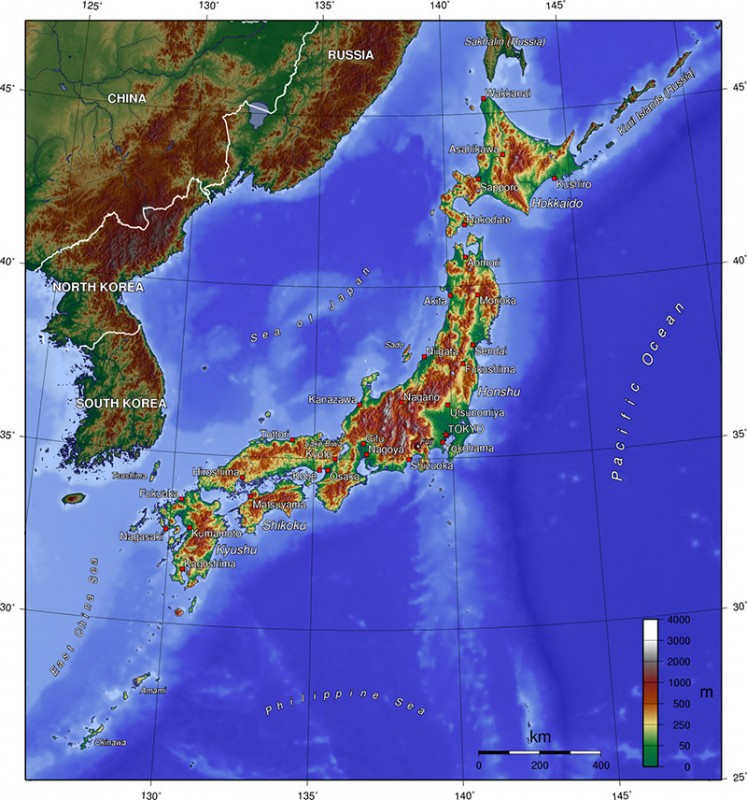

If you had to pick the definitive aspect of Japan that shaped your wilderness experience, it would be this: Japan is hilly. Really, really hilly. It didn't take long for your aching legs to conclude that wide, flat areas are hard to come by in this country. Getting around was a constant up-and-down affair.

On the other hand, the dominance of mountainous terrain (which you eventually discovered covers about three quarters of the country) made for visually complex, exhilarating hiking, with many hidden surprises. In particular, you enjoyed the effect of rough terrain on Japan's rivers, which often fell in cascading waterfalls and rapids.

Of course, the undulating landscape only makes sense. Japan does lie along a fault line (from whence it came), and therefore sits in a tectonically active region. That means earthquakes and volcanoes, with mountains rising from colliding plates and spurting lava.

Another feature you encountered throughout Japan is the "monsoonal" climate; that is, the annual cycle of wet and dry seasons. Specifically, Japan generally features wet summers and dry winters. The prominence of the monsoonal cycle varies by region, as you became intimately aware from your ever soaked hiking boots.

The general abundance of precipitation ensures that forests are the predominant natural biome throughout Japan. Thus, if someone were randomly plopped down somewhere in the Japanese islands, they would most likely find themselves in the midst of forest-covered hills.

You encountered many forms of wildlife that inhabited all three climate regions. Mammalian examples include foxes, boar, deer, and tanuki. Widespread birds included cranes, pheasants, woodpeckers, and owls, the latter of which hooted you to sleep at night. Reptiles were represented by snakes and lizards (which didn't help you sleep at all).

So now that you've touched upon the widespread natural features of Japan, it's time to move on to the specifics.

Hokkaido – Mild-summer Continental

A continental climate features a wide temperature range throughout the year, with warm summers and cold winters. In contrast, temperate climates feature less extreme temperatures (namely milder winters), while tropical climates are warm year-round. Though continental climates generally occur inland (hence the name), Japan is an exception.

Continental climates are divided into "mild-summer" and "hot-summer" subtypes. Japan's northernmost climate, which roughly covers Hokkaido, is of the mild-summer variety. This climate also prevails in the northern United States/southern Canada, as well as Eastern Europe.

Hokkaido is the northernmost of Japan's four main islands. You decided to start here, reasoning that it would be nice for each year of your journey to be warmer than the last. The island also lured you in with its romantic reputation as the far off, untamed wilds of Japan.

So what was it like? Summer days were usually comfortably warm, while winter days were generally below freezing. Day/night temperature shifts were often dramatic. Many times you wondered why on earth you were sleeping in a makeshift hut in the frigid Hokkaido wilderness.

Summer and autumn were fairly rainy, often with dense sea fog, while precipitation was low the remainder of the year. Interestingly, the west coast bucked this trend; a winter hike along this coast had you trudging through heavy snowfall. You criss-crossed the island several times, noting that temperature and rainfall dropped markedly among the inland mountains.

The northern and high-elevation parts of Hokkaido were filled with conifers (trees with narrow evergreen leaves, aka "needles"), primarily spruces and firs. You discovered that the very coldest parts of the island couldn't support the growth of full-size trees, instead housing sub-arctic vegetation, including dwarf pines. At lower elevations and latitudes, the coniferous forest gave way to deciduous trees, which feature broad leaves that drop in the autumn. These forests were made up largely of oaks, beeches, and maples.

Regarding animals, one encounter stood out above all others. When you came over the top of a hill one day, you found yourself almost face-to-face with an enormous bear: the Ussuri brown bear (though you really didn't care much about the name at the time)! Fortunately, it wasn't interested in you… maybe you were too skinny at this point for it to bother.

Northeastern Honshu – Hot-summer Continental

After your first year, you happily crossed the Tsugaru Strait to Honshu, the largest of Japan's four main islands. The second major Japanese climate region, "hot-summer continental," lies mainly in the northeast part of this island. This is actually a fairly rare climate, also found in a few slivers of Eastern Europe, as well as the southern states of the American Midwest.

Winter was milder here, it tended to remain above freezing, while summer was hotter. The rainy period (summer/fall) was heavier, and lasted longer. Once again, precipitation was scarce in winter, except along the west coast. You thought moving south might leave the snow behind, but there was still plenty to be found in the northern and interior portions of Honshu.

Though you discovered stands of coniferous forest in the mountains, deciduous trees were more prevalent, as in southern Hokkaido. In terms of animals, you were hoping to leave those enormous brown bears behind, and you did… only to find that the remainder of mainland Japan is home to the Asian black bear! Luckily, you avoided any further close encounters.

You also spotted several green pheasants, a distinctive creature you later discovered to be the national bird of Japan.

Central/Southwestern Japan – Subtropical

With the second year completed, it was time to move on to the final region: central/southwestern Japan, spanning the remainder of Honshu, as well as the other two main islands, Kyushu and Shikoku, and some additional smaller islands. Here, the climate finally made the leap from continental to temperate. In fact, it leapt all the way to subtropical!

This climate encompasses most of the population of Japan, including the nation's four largest cities: Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, and Nagoya. Compared to the more northerly parts of the country, the subtropical region features a longer spring and autumn, and thus a more even balance between the four seasons. Other parts of the world with a similar subtropical climate include eastern China, as well as much of the American South.

As you expected, temperatures rose again as you journeyed south, with hotter summers and milder winters. Monsoonal rainfall became even more pronounced, with higher duration and intensity of the wet season. Once again, the west coast maintained atypically high precipitation throughout the winter.

While you continued to find deciduous trees in higher elevations (and conifers even higher), lower elevations were often filled with laurel forest. This forest type consists of evergreen broadleaf trees, including camphors, pasania, evergreen oaks, figs, and palms.

Throughout this region, your most striking animal encounter was the Japanese giant salamander, the largest you'd ever seen! You also met sea snakes one day while out swimming, which made you wonder if bears were really so bad after all.

Back to Civilization

Your restlessness satisfied, you returned home filled with memories of Japan's diverse environment. There's nothing like being in touch with nature.

After three years, however, you may have had enough nature to last you a lifetime. The next trip you make to Japan will focus on the most densely populated areas you can find. And it will take place largely indoors.

-

Note: Do not actually try living in the Japanese wilderness. Seriously. But just in case you need convincing, here are some very good reasons why it's a terrible idea. ↩