Why play Go? Go is simpler to play than chess but harder to win. Go is older than Japan yet you can see it being played every Sunday on Japanese Channel 3. Go starts with an empty board then builds until the game looks like a work of art. Most importantly, Go is an awesome abstract strategy board game with an almost entirely Japanese vocabulary that you can learn to play in the time it takes you to read this piece I wrote to teach you how to play it (and it’s pretty short, trust me).

Go Culture

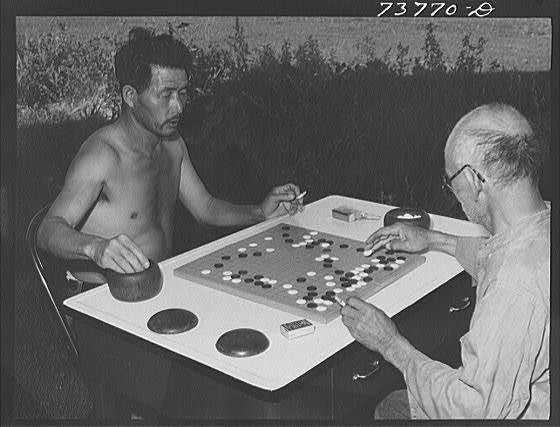

Go is like chess (the western kind or the Japanese version, shogi) except its rules are simpler and the resulting game is more complex. Go looks a lot like Othello/Reversi (black and white stones on a board with a grid of lines) and there’s a cool anime and manga series about it called “Hikaru no Go.” Also cool: Despite all kinds of efforts made by programmers, computers still aren’t very good at Go. Unlike chess, Go programs only very rarely beat professional players.

Japan started playing Go a long time ago, in the Nara period, in the 8th century. But the exact same game has been played in China for much, much longer: Confucius and his followers wrote about the game in the Analects in the 5th century BC. The game has been played by Chinese aristocrats for almost the entirety of recorded history, and it has hardly changed. Back then, they played on a 17×17 grid instead of 19×19, and there were no komi compensation points for the player who goes second. Those are the only major differences between how the game is played now and how it was played by the Zhou Dynasty 2500 years ago.

There is actually a huge network of Go players out there in the U.S., Canada, and the rest of the world. I found people to play against in my small hometown, and my small college town, and there is always a huge community ready to play online.

The only downside: No one can decide what to call it in English. We mostly call it “Go,” based on the Japanese name: Igo. Unfortunately, Go is already a super common English word, so I have to capitalize it every time (unlike chess or shogi) and it’s just about impossible to Google anything about the game without using one of its other names. In China, it’s called weiqi, and in Korea, baduk.

Go also uses a cool ranking system to determine handicaps, so you can officially or unofficially “level up” as you get better at the game. Like in judo and some other martial arts, amateurs start at something like 20 or 30 kyu then work their way up backwards to 15 kyu, 10 kyu, and eventually 1 kyu. After that the next ranking is 1 dan, which goes up from there to 7 dan. Even before I was any good at the game, saying I was an 18k level player was always fun and it was rewarding to move up the ranks by beating higher-ranked players.

The Rules

The rules of Go are deceptively simple. Though there are variants, the traditional and by far most common game is this:

- There are two players. One uses black stones and the other uses white.

- They take turns placing stones on any intersection on a 19 by 19 grid of lines (19 is just the most common. The board can be any rectangular size from 2×2 to 786×918 if you want). They may put a stone anywhere that does not already have a stone (except for spaces where their stone would be captured).

- A stone or group of stones is captured when there are no empty spaces adjacent to it. Kind of hard to explain, so check out some examples here. Captured stones are removed from the board and those spaces are now empty and new stones can be played on them.

- The goal is to surround as many board spaces with stones of your color as possible by the end of the game.

- You get a point for each space you surround with your stones, and you get a point for each stone you captured during the game. The white player also gets komi points due to black’s advantage in going first. Usually the komi is 6.5 or thereabouts, with the .5 added to break any ties.

- You can’t play a move that takes the game back to exactly where it was previously. This is the only kind of weird rule, and it’s just to prevent the (fairly common) ko situation, in which both players can capture each other in the same spot over and over. Don’t worry about it.

That’s it. Nothing so complicated as chess and every piece’s different maneuvers. Now you know how to play, but the question now becomes “Where the heck do I put my pieces on this giant board?” We’re going to go over a little bit of basic strategy in a moment, but it’s a huge, endless subject, and maybe the best thing to do would be to play a few quick games. At this site, you can play against the computer on different board sizes. Play some games on a 5×5 board to start getting a feel for when pieces are captured and how the game is scored. Then come back here and read on for some strategy and where to go next.

Strategy

Hoo boy, here’s where it gets complicated. If you’re playing on a 19×19 board, you can feel completely lost at the start of a game when you don’t really know how to play. And it doesn’t get any easier after that: How do you create territory? What do you do when your opponent creates huge territory but doesn’t solidify it with more stones? How do you know a piece can’t be taken? Let’s go over a few of those questions right now.

Where do I play my first turns?

Like chess, Go has a lot of opening strategies. A standard 19×19 board is huge, and with no experience playing or watching Go, the number of choices can be overwhelming. Thankfully, a standard board has something to help guide you: The bold spots on the intersections in the corners, center, and sides, called the hoshi or star points. Boards will almost always have the star points or hoshi emboldened, as you can see here:

Because the game is about building territory, it’s recommended that you play first on the corners. It takes fewer stones to make viable territory in a corner, so the corners of the board are valuable. The most popular spots to start are either on a corner star point or on the third line from the side next to a star point. After claiming two corners with a stone each, you can either fortify those or move to a side star point and begin creating influence on a side. Or you can choose to attack one of your opponent’s corners. There are too many choices to mention in a beginner’s guide.

Why not play first on the center spot, also called tengen? The center spot is a very strong opening move on smaller board sizes, but on the 19×19, a single stone in the center doesn’t have enough influence on eventual territory to be considered a viable opening move. There is a “gimmicky” or “silly” opening strategy called the Great Wall which involves playing first on the center spot which can be effective if it’s not played against inventively. But don’t get too bogged down in thinking about your opening. In general, play in the corners, then the sides, and then the center, and you’ll have the right idea of building territory in Go.

How do I take my opponent’s stones?

First of all, most of the common beginner’s mistakes in Go come from trying too hard to take your opponent’s stones. It’s very hard to capture stones against a competent opponent. Some captures will happen in every game, but you don’t win by trying to kill your opponent. You win by building the right amount of influence in the right areas to build as much territory as possible, while making sure you only play in areas where you can build a living shape (more on that in a second).

That being said, if you want to figure out how to incisively attack your opponent’s groups, try some Go problems. These are constructed Go game scenarios that primarily build your ability in protecting your groups and attacking your opponent’s groups a few moves at a time. It’s not the most important skill to develop right away, but with enough practice on Go problems, you will start to naturally understand how to attack and defend.

When are shapes “alive” and when are they “dead?”

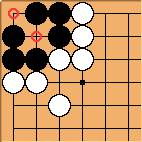

Groups of stones form shapes, and those shapes can be eaten whole by your enemy no matter how big they are if they don’t have any empty spaces around them. The key to keeping a shape alive is to give it “two eyes.” No matter how big or small, a shape that fully surrounds two empty spaces (little holes in your shape that almost look like eyes) cannot be taken. Here, the black group here has two eyes and cannot be taken:

If you only have one eye in your shape, then your opponent can completely surround that shape then put a stone in the eye, taking your stones’ last empty space and capturing each stone. He can’t do that if the shape has two eyes. He would have to take two moves at once to fill in both holes and take the shape, and he can’t play a stone in a space that’s surrounded by your stones unless it kills the shape.

That’s why a shape with two eyes is called “alive” and a shape that cannot create two eyes is “dead.” Once a shape can’t possibly make a second eye, there’s no point in playing stones in that shape any more.

What Now?

Find a Go club! Nerds like me are always thrilled to teach the game to new players to feed our egos, so virtually any Go club is friendly to newbies. The American Go Association keeps a list of clubs, and this Google map also has quite a few on it. Even more can be found on Meetup.com or BoardGameGeek or other websites where someone might try to find other Go players.

If you’re not a fan of real human people, or if you’re too anxious to wait five whole days for the next Go club event, I would recommend KGS. It’s a popular online Go server that keeps track of your stats and archives your games for you. There are specific rooms for beginners, so you can find a game with other weak players and play online quickly. You can even play computer opponents through the internet through KGS if you want, though there are plenty of other programs you can download if you just want to play a computer.

If you’re not in the mood to play, you could read about the game at Sensei’s Library, a wiki about Go. You can learn about anything there from strategies to terminology (like atari, hane, and monkey jumps) to reports of famous games in the history of Go.

You can also start following professional Go. Go is covered almost like a sport in China, Korea, and Japan, with newspaper and TV coverage of the top competitions. With the right software, you can download game replays from big competitions like Japan’s Kisei Tournament and click through them move by move, sometimes with commentary added. It will be hard to understand the details move-by-move until you know a lot more about Go, but it doesn’t hurt to see a few professional games just to get a sense of how things should generally look in a real game.

You can also buy books, or watch Hikaru no Go, or play around with weird Go variants, but that’s all ahead of you for now. There’s so much to learn about the game, and who knows? Maybe you’ll be a genius and you’ll become a professional player, touring the world and making money with mind sports. You’ll be up against players who have studied the game since they were five years old, nothing’s impossible.

Go may be the deepest board game of all time, and it’s fun to play at any level. Give it a shot, learn some new vocabulary and culture, and you’ll come away smarter even if you decide not to play much more of the game. Meanwhile, I’ll be reading my big book of joseki and battling it out online with some 12 kyus.