If you have never uttered the word bishounen with swooning exhalation, then, you are most likely a straight male with a floating thought bubble filled with question marks above your head just about, now. The other nth of you prefer your men folk clearly defined by pronounced Adam’s apples, brow ridges, large hands, and husky voices or thereabouts.

For those on the adoration side of the aisle, if you could, you would not have your men any other way than bishie, but that is impossible.

Bishounen are not men. They are not youths engaged in pederasty. They are not actually “pretty boys” as many otaku running in anime circles might insist. These beguiling beings are not superlative in any form, not really.

Idealization Of Youthful Male Beauty

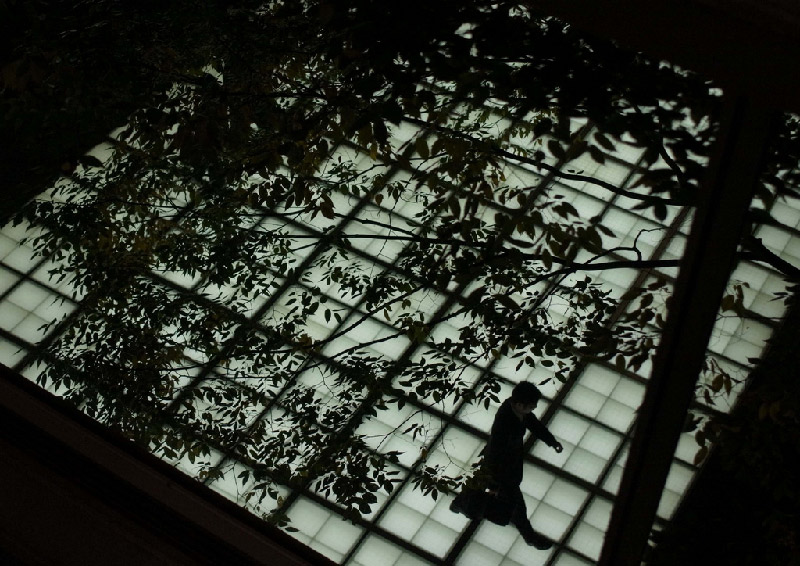

These are boys who cannot grow up. They are Japan’s answer to Peter Pan and Twilight. In essence, bishounen are specters whose very existence defies Western conventions of masculinity. They are seemingly asexual harbingers of tragedy, who choose neither the path of manliness nor femininity.

From afar, bishounen exhibit perfect qualities of youthful boyishness without any of the detractions of adult responsibility. This does not mean they cannot perish. At first glance, they appear to be flaunting their youth while at the same time tempting Death. The tragedy lies in everything bishounen are not.

Bishounen are often connected with the ancient Japanese literary works known as chigo monogatari. These pederastic love stories were written by Japanese priests during the Muromachi Period between 1337 and 1573 in such quantity that modern day scholars classify the prose as a genre. The stories focused on the relationship between a Buddhist cleric and their beautiful boy acolyte, with the later often finding a tragic end. Some tales depict absolute erotica, while others reveal more noble outcomes toward enlightenment. The acolytes in these stories only share two similarities with bishounen: they are beautiful and forever boys.

This Is Where The Fantasy Ends

The reality is that chigo (acolyte children) “participated in formal processions, religious ceremonies and public functions,” and would also “serve meals, receive guests and attend closely to the master.”

In exchange, the chigo were granted unusual privileges that were not given to the other temple children. They were permitted to wear their hair long (waist length, in some paintings), powder their faces, and dress extravagantly. (Chigo in the Medieval Japanese Imagination)

In manga, these beautiful boys are often indifferent protagonists. Western readers may perceive bishounen ambiguity as effeminate, but that is a misreading. Bishounen as perceived by the Japanese audience is neither effeminate nor ambiguous; rather they are seen as something like angels, wholly male and female. Thus the character is sexually liberated, or is it the Japanese reader who is freed from their own traditional social restraints?

“But if the primary Japanese readership is female, shouldn’t these liberators be female as well?” asks the feminist. Yes and no. Bishounen are masculine insomuch that they assume this role. On the other hand, bishounen are feminine in that they disregard this perceived maleness.

And that is what makes these males endearing to the masses of Japanese female readers, bishounen’s sensibility of character apart from their sexualization. Of course, a significant part of this dynamic is how they are drawn. Bishounen are distinctly neither male nor female in appearance. By convention it is assumed those are male clothes, a boyish cut, and figure. Soft features upon lanky frames with stylish hair, these boys are literal representations of asexual aesthetic. More than this is the perceived vanity which female readers are connecting with, an ironic paradox, since the corporeal male aesthetic does not regard the mirror.

For the bishounen, this vanity is not calculated; instead, it is a misinterpretation by other characters, the ones we as readers define sexually and thus impart our social expectations upon. Just as Peter Pan in Broadway productions is historically portrayed by women with a tap upon their nose, so bishounen give us a nod and a wink.

Readers Are In The Know

Androgyny further lends to the bishounen’s heightened vanity by literally drawing attention to it. Like runway models with boyish figures, there is a reason this body type remains the go-to form upon the catwalk. Yet unlike fashion models, bishounen protagonists, being male, are immune to the criticism of feminist rhetoric. In essence, bishounen are idealistically feminist while remaining wholly male.

And while many readers claim bishounen to transcend gender, it is all important to recognize for whom bishounen are created. Western gender roles need not apply.

Cultural Contamination Skews Perception

One casual Saturday, I was able to visit Book-Off for second opinions, firsthand insight and to glean some reading material. Cautiously navigating the stacks, I spotted several customers lining the bishi aisle AKA shoujo section. Having my Girl Friday in tow, we approached with quasi sumimasen bows.

“Lots of bishounen read like total chauvinists, not just in my American mind, but I think universally. They can often be purposefully insensitive,” I said to our first participant.

Mari, 33, Office Lady

“Exactly! It’s because they are guys, they have that choice,” Mari exclaimed. “No, but when bishi are jerks, don’t you hold it against them?” I instigated. “Never, they’re too beautiful to hate forever; I just couldn’t. I always give them a chance. I hope they change, but it’s okay if they don’t. As a shoujo reader, I’m optimistic, but that doesn’t mean I’m right. Heartache is fun when it’s not your own.”

Kyou, 28, Salaryman

“Excuse us, but are you reading shoujo?” “No, I was, yes.” “Wonderful! Do you have any opinions about bishounen?”

The man thought about the question so long we thought he was ignoring us and when he finally spoke, Yo-yo and I had already moved several bookshelves away.

“Yes. I have an opinion!” the man proclaimed.

Seeing Both Sides Of The Coin

“I think they’re…cool.” “What do you mean?” “They’re cool. Bishounen don’t give a damn; they do what they want, and more importantly, how they want. They act in a way I would never dare,” Kyou stated.

Yo-yo and I studied the salaryman. He was tall, slender, and perhaps even bishi in a way. His glasses flashed whenever he cut a look toward us.

“Why do you think Japanese women swoon over bishounen?” He tilted his head as if we’d asked him the impossible. “Men or women, it’s the same really: the fantasy. I never swoon, but sometimes I sigh.”

Sanami, 21, University Student

“Well, I find that most bishounen are just a convention these days. They’re often alien or magical or something like that. I’m not really a fan, but I tolerate them as supporting characters.” “That means if the lead character is bishounen, you won’t read the manga?” I asked. “Well, I might still read it. I just might not finish it. I know why office ladies love these characters, but it’s not my thing. Like I said, I find bishounen really conventional.” “Sorry, and why do office ladies love them?”

At this point, Mari rejoined the conversation as Kyou eavesdropped some distance away.

Mari: We love them because they’re on the other side of that glass ceiling. I don’t mean that in a corporate sense. It’s…”

Sanami is nodding. “She means it the way people often see the grass as always being greener on the other side of the fence. Bishounen are on that other side. They’re this kind of social hybrid.”

Mari: Exactly! And the fun is knowing that the grass isn’t actually greener at all, it’s blue or pink, it’s different, not better.

Me: So you’re saying that this “glass ceiling” mandates that bishounen must be male? Or that bishounen actually reinforce traditional gender roles?

Yo-yo bats her eyes in my direction.

Sanami: This is why I dislike bishounen. I know they’re male because of convention, while they’re actually supposed to be this ambiguous beauty thing.

Mari: I don’t think it’s defined so clearly, but there is a kind of formula these days. An expectation I guess. It goes with the territory, and I love it. It’s my escape.

Me: What about female empowerment?

Yo-yo: What about it?

Me: Ask them!

Yo-yo translates.

Mari: Oh that, yes, there is that. I’m moved, and sometimes I think about how differently bishounen might handle a similar situation I find myself in, like when I am expected to serve tea at business meetings merely because I am a woman. Sometimes I wish I was irresponsible.

Me: Right, that means you think of bishounen as a kind of man-child?

Sanami: That’s totally wrong. They are their own thing. Bishounen don’t actually exist, right, since this is part of the convention.

Mari: That’s right, they can only exist in manga.

Yo-yo is laughing.

Me: What is it?

Yo-yo: If every Japanese man were to suddenly disappear, oh nevermind!

Sanami: I know what she’s thinking. Bishounen are the way Japanese women would act if they were to assume the masculine role.

Me: So why don’t Japanese women simply assume that role?

Mari is laughing, but stops suddenly as Kyou appears.

Kyou: Because they are still women.

Me: ???

Yo-yo: Feeling empowered and being empowered are two very different things.