Even as a child, I sensed something different about cartoons like Robotech and Voltron. Compared to other shows, they struck me as serious, dramatic and stylish. Each episode contributed to a longer narrative and when something changed, it remained that way for the rest of the series. The straight-lined art affected me me in a way other cartoons' softer, rounded styles never did.

Something was different, though I couldn't put my finger on it.

At the time I didn't know these cartoons came from Japan, where they had different titles, and occasionally different narratives. I didn't know that one day I'd become a fan of the medium, a style of cartoon called anime.

Anime differed from standard Western cartoons. Back then anime fans would tell you, Japanese anime is better. Cartoons are "kids' stuff." With complicated stories, deep character development and themes fit for adults, anime eschews the label of cartoon and makes claims on being a higher art-form.

Of course anime's visuals fuel its purported pedigree. Fans laud anime for its detailed art, style and fluid animation. Wait… fluid animation?!

嘘つき! Liar!

In reality, what set anime apart from other styles is its deliberate lack of fluidity and use of limited-animation. By ignoring the era's animation standards, animation studio Mushi Pro revolutionized the medium.

And by taking advantage of two factors – television's access to Japanese households and the popular manga series Astro Boy – Mushi Pro created both Japan's first anime as well as its first anime boom. Mushi Pro's ingenuity created a controversial style of animation that lacked animation and this deceptive style and marketing tradition continues today.

Anime's Success Ingredient 1: Television

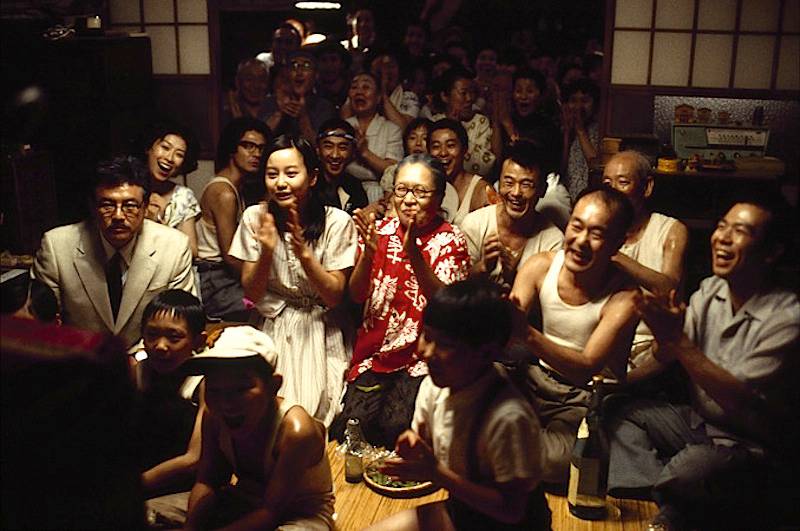

Television's proliferation in Japanese households provided the access anime needed to reach its audience.

Japan's post-war era saw furious physical reconstruction and economic growth. Mass and personal transportation made commuting possible and helped cities grow. With a rebuilt infrastructure, Japan's economic boom hit full swing.

After prices leveled out and necessities became readily available, households had more spending money than ever before. Affordable commodities like refrigerators, rice cookers and washing machines made life more comfortable (especially rice cookers, which have an awesome history). The economic growth continued.

For the first time, average people could afford the extravagant. Television ownership boomed. "In 1960, 55 percent of households owned a TV set, by 1964, TV ownership had grown to 95 percent, owing… to the crown prince's televised wedding in 1959 and the 1964 Olympics" (Steinberg). Widespread TV ownership gave broadcasters access to nearly every household and allowed the country's first anime series to take Japan by storm.

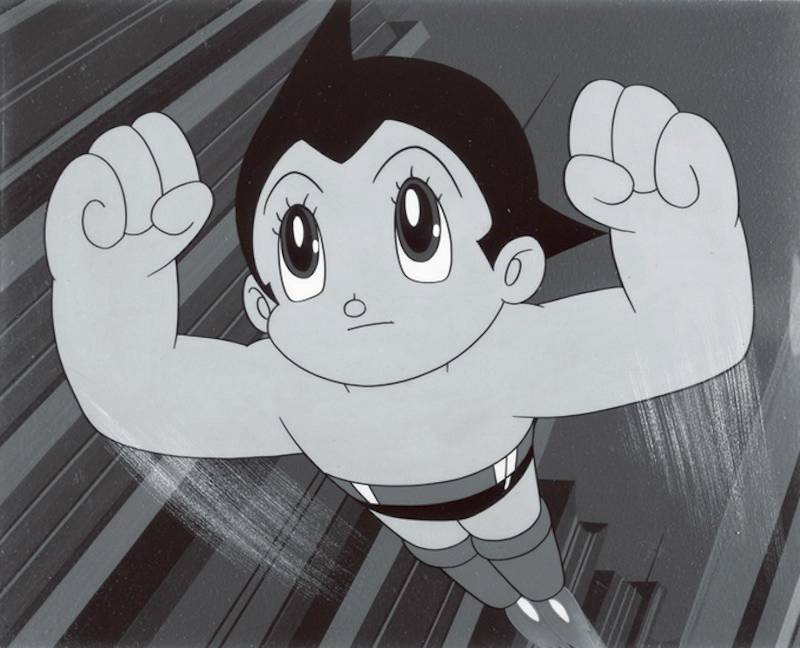

Anime's Success Ingredient 2: Astro Boy

As we learned in Michael Richey's Anime Before It Was 'Anime', Japanese animation dates back to the early 1900's. But pre-war productions are best described as cartoons, not anime. Richey explains, "Anime, as we all know it now, began with Osamu Tezuka's style and production methods and everyone in Japan following his lead."

Prior to Osamu's Astro Boy, or 鉄腕アトム, animation occupied a marginal position in Japan's cultural consciousness. Japanese studios faced limitations that made competition with foreign studios impossible. Meager budgets meant Japanese studios faced an uphill battle against foreign features' financing, sound and color (Hu).

Although the need for wartime propaganda fueled the production of pro-war cartoons like Momotaro's Divine Sea Warriors (1945), the war effort, government censorship and widespread destruction stifled Japan's manga and animation industries.

After the war, Japan's movie studios looked to beautiful animation from abroad for inspiration. Fully-animated features from China and the US provided the blueprint. Instead of forging their own path, Toei, Toho and other Japanese studios sought to imitate their foreign rivals.

As a result, Japan's studios produced theatrical features. Despite Japan's intense post-war recovery, animation remained too time consuming and too cost prohibitive for television. But Astro Boy's 1963 debut changed everything.

"Manga god" Tezuka Osamu aimed to do the impossible and conquer the television market. His animation company Mushi Pro ignored the era's animation philosophies, goals and influences. When all was said and done, Mushi Pro's Astro Boy anime rocketed to popularity and sparked a paradigm shift in Japan's animation industry.

Forging a New Path

In the West "anime" means "animation from Japan." Myanimelist, a Western anime and manga databasing site, refuses to list a series unless it's Japanese (to the chagrin of Avatar: the Last Airbender fans).

However, the average Japanese person considers all forms of animation to be "anime," regardless of style or country of origin. I've even heard live action series like Kamen Rider, Metal Heroes and Super Sentai referred to as "anime" in conversation.

But industry insiders and purists (Hayao Miyazaki for example) define "anime" as a "limited-animation" style popularized by Japanese studios. Envisioned by Tezuka Osamu, limited-animation techniques lowered production costs while speeding up the production process, making animation feasible for television broadcast.

The full animation made famous by Disney and embraced by Japan's studios used too many cels (the transparent sheets artists drew and painted images onto, then layered and photographed to make a frame of animation), required too large a staff and took too much time to make its production suitable or even possible for TV.

However, Osamu realized animation need not be fluid or fully animated to be enjoyed by audiences. After all, by flashing still images in rapid succession, even live action films create a flase illusion of motion.

Film theorist Christian Metz explains,

Motion… is always perceived as real. Since motion is never a tangible thing… there is no difference between the perception of motion in everyday life and the perception of motion onscreen. (Steinberg)

Mushi Pro, Osamu's studio, developed a style of "moving manga" noted for its "limited" animation. Associate animation professor at Kyoto Seika University Nobuyuki Tsugata writes, "From the start Tezuka… intentionally created anime, not animation." (Steinberg)

As the first television anime, Astro Boy reused cels, relied on visual and audio tricks and used fewer frames of animation to create an illusion of full motion.

Mushi Pro's Yamamoto Eiichi explained, "In the end we completely did away with the techniques of full-animation. Then we adopted the completely new technique of making the manga frame the basis for the shot, moving only a section of this frame." (Steinberg)

Audiences loved the result. Astro Boy became the first official "anime" and gave birth to the popular, marketable style than continued through the likes of Tetsujin-28, Neon Genesis Evangelion, and onward.

The Difference Between Anime and Cartoons

Through Astro Boy, Mushi Pro created a style of animation that relied on stillness, giving their anime a specific style and nuanced definition. Nobuyuki Tsugata explains the result,

Anime is an animation form that 1) is cel based 2) uses various time and labor saving devices that give it a lower cel count… and 3) has a strong tendency toward the development of complex human relationships, stories and worlds. (Steinberg)

Marc Steinberg adds three tenets to the list, 4) anime is organized around distribution outlets (like TV and DVD) 5) it is character-centric 6) it is inherently transmedial."

Miyazaki Hayao's Studio Ghlibli, rejects anime's style and techniques. In The Anime Machine, Thomas LaMarre recalls how Studio Ghibli documentaries and exhibitions

almost completely exclude those forms of Japanese animation that commonly fall under the rubric anime. Clearly the goal… is to shore up a lineage of Japanese animation (called manga film) that stands in contrast to anime.

By refusing to call his films "anime," Miyazaki draws a definitive line between anime and other forms of animation (Steinberg).

Limited-Animation's Definitive Techniques

What techniques made Astro Boy, the first televised anime possible, and why? Some sped up production. Others cut costs. Although each technique served a convenient purpose, the following techniques created anime's appealing and striking style.

1. Three Frame Shooting

Full-animation features twelve to eighteen unique images per second. The result is smooth, fluid, "life-like" motion. Limited-animation uses significantly fewer frames. On average, anime studios employ eight images per second, but fewer frames can be used (Steinberg).

Mushi Production staff "got away with only fifteen hundred to eighteen hundred drawings per twenty-five minute episode… The same program length done in full-animation would require around ten times that, or eighteen thousand drawings." (Steinberg)

Although less fluid, anime maintained the illusion of motion. Three-frame shooting cut production costs and time and became an anime standard.

2. Stop-Images

In cases of location and crowd shots or facial close-ups, Mushi Pro employed a single, still image. By blocking or obscuring a character's mouth, animators even utilize stop-images in scenes where characters speak. When cast among the rhythm of other shots, accompanied by music, sound-effects or narration, the image's stillness goes unnoticed.

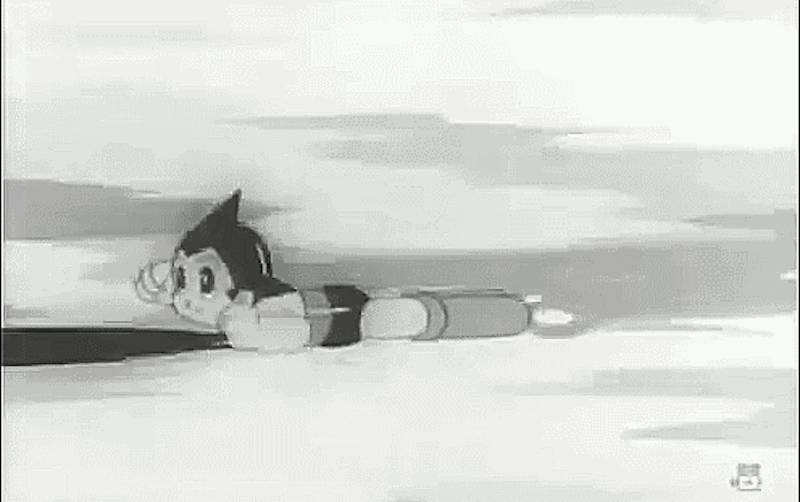

3. Pull cels

When a character or object crosses the frame at a fixed distance, animators found redrawing or fully-animating the image redundant.

Instead, animators move the single animation cel across the background. One cel does the work of many, saving time and money. Although the character or object appears to move, it is a still image. Once again animators create motion despite a lack of true, fluid animation.

4. Repetition

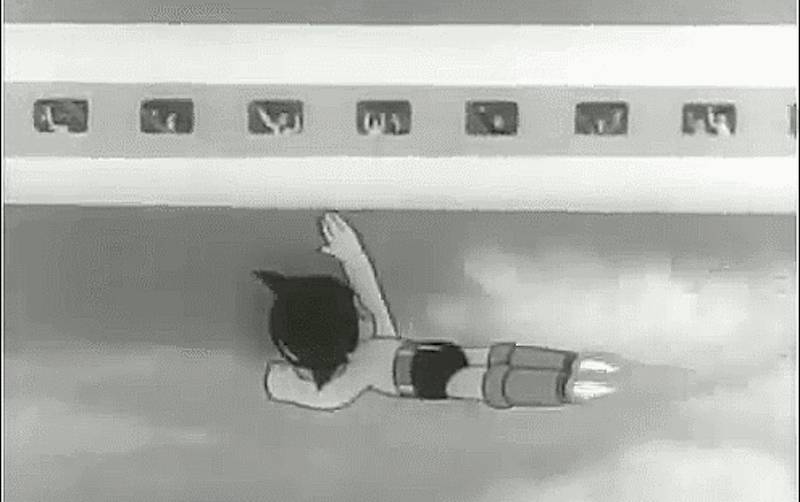

The technique of repetition relies on the reuse of cels or animated sequences within a single sequence. For example, a running character maybe reuse the same "running" cels several times while the background scrolls to create the illusion.

5. Sectioning

In sectioning, parts of a shot are animated while others are stop-images. In the picture above, Astro Boy's body is a single, fixed cel. His arm is a separate image that the animators manipulate to create motion.

6. Cel Banking

Cel banking involves reusing the same animation cels and therefore same animated sequence (Steinberg). For example, a single Astro Boy flying sequence might be reused throughout the series' production. When cel banked sequences are viewed in succession, the trick becomes obvious. But disguising their reuse with rhythm or different backgrounds creates the illusion of original movement despite repeated viewings.

6. Lip-Synching

Through lip-synching, mouth cels are animated over a static face. Audiences focus on the mouth and dialogue while ignoring the still image. Short shot length and rhythm hide the fact that only the mouth moves. Just as face cels could be banked and reused, animators used these mouth animations again and again.

8. Short Shot Length

Short shots and editing rhythm don't give audiences time to realize images lack animation. Quick cuts create rhythm and hide static images, creating the illusion of animation.

9. Special Effects Layers

Special effects layers are cels placed over a still image to create onscreen effects without full-animation. Beads of sweat dripping down a character's face, tears, rain, the sparkle of an eye, and the pulse of a vein all create the illusion of animation. Effects appear and move as a pull cel (sweat rolling down a face) or in repetition (falling rain).

10. Camera Movement

Camera techniques also help fake movement. Pulling away, zooming in, panning across a shot, or fading in or out creates a sensation of movement without actual animation. Animators couple the shots with narrative or other sounds to further distract viewers and complete the illusion.

Mushi Pro did not invent these techniques. The studio's influences include animated television commercials, Hanna Barbera cartoons, and Japanese traditional theater. But Mushi Pro mixed old techniques with the new and created a stylized form of animation fit for television production.

The Virtues of Limited-Animation

Limited-animation succeeded by decreasing production time and costs – two factors vital for television broadcasting. Here's how.

The reuse of animation cels lowered costs by decreasing the need for supplies like blank cels and paint. Animators spent less time drawing and coloring since limited-animation used fewer unique images. These factors allowed studios to meet television's high paced production.

Studios based anime series off of preexisting manga which meant staff spent less time and effort on development since plots, story boards and dialogue had already been planned out. Basing anime on manga also provided pre-established exposure and fan-bases that original series lacked.

For a full-animation production, high level artists spent countless hours drawing and redrawing characters frame by frame. The costly process consumed time and resources. By utilizing techniques that saved time and money, limited-animation streamlined the animation process with industrial efficiency.

Limited-animation removed some of the artistry from the production process. Studios outsourced episodes and in-between animation cels to other studios or unskilled labor. The strategy allowed for faster, cheaper production. Although the practice has come under fire, outsourcing has been a common practice since the dawn of anime. In fact, Mushi Pro outsourced production of the original Astro Boy series, relying on Studio Zero and P Production to produce some episodes (Brubaker).

By ignoring the animation industry's original goals, Mushi Pro's Astro Boy proved animation could be produced for television. From its reuse of animation cels to its reliance on manga and outsourcing, limited-animation makes production faster, cheaper, and more efficient.

Limited-Animation's Unlimited Style

Limited-animation's time and cost cutting techniques lead, whether intentional or not, to anime's definitive style. Marc Steinberg explains,

Unlike the full-animation of Disney, limited-animation relies on the minimization of movement, the extensive use of still images and unique rhythms of movement and immobility… We must think of limited-animation not in terms of immobility but rather in terms of the very mobility of the still image… a different kind of movement or dynamism.

Limited-animation's lack of movement empowered static images; anime's style struck audiences in ways full-animation never did:

Instead of (creating) fluid cinematic movement across the screen or within a world, limited-animation allows bodies to leap from field to field, from image to image, and even from medium to medium. (Lamarre)

In other words, limited-animation's deliberate cuts and rhythm of images creates sensations absent from traditional fluid animation. While full-animation can be beautiful and breathtaking, limited-animation trills viewers with stylized editing, bold still-shots, cool poses and dramatic effects.

Moreover, static images make characters recognizable by their silhouette or trademark poses. Limited-animation favors character and graphic design over actual animation.Thomas LaMarre explains,

As limited-animation deemphasized full-animation of characters, it increasingly stressed character design, and the degree of detail and the density of information became as important as line, implied depth, and implied mass… Limited-animation tends toward the production of "soulful bodies," that is, bodies where spiritual, emotional, or psychological qualities appear inscribed on the surface.

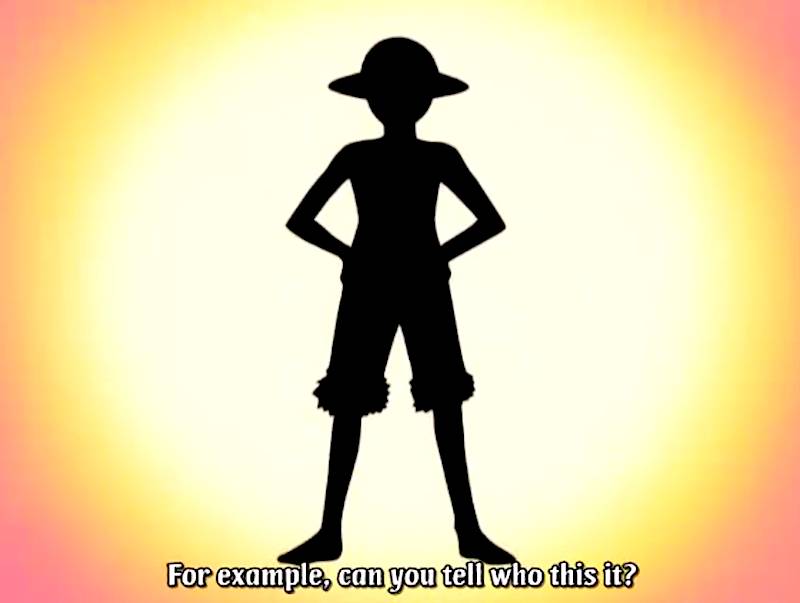

Character details, like hair styles, outfits, and accessories, allow viewers to draw conclusions about characters with just a glance. The trend of character design and reliance on superficial imagery like cat ears and eye patches has fueled the moe 萌え boom.

Anime reproduces manga in ways live action cannot. Animation studios recreate a manga's style, angles and at times exact panels for their animated versions. Marc Steinberg writes, "The same character, in the same drawing style and in the same poses, now inhabited manga and anime alike – not to mention the other media forms to which the character image migrated."

Limited-animation's inherent style created striking, recognizable and stylized imagery. Anime series recreated manga in ways live action and fully-animated productions did not. And so limited-animation's limits became the style's greatest strength!

Synergy: A Marketing Dream Come True

Limited-animation lends itself to "synergy" or a "product mix" between media and consumerism (Lomash). Television anime reaches a wide audience and creates new fan-bases for pre-established manga and characters. Fans take pride in supporting their beloved series through consumption. Anime's market synergy crosses mediums including film, games, music, figures and accessories.

Anime's still images offer potent marketing synergy. Character silhouettes warrant instant recognition and cheap reproduction (Harvey). Character poses, logos (like One Piece's logos) and other trademark characteristics (official straw hats) lend themselves to brand recognition. Steinberg states,

The dynamic immobility of the image and centrality of the character are also what have allowed anime to forge connections with toys, stickers, chocolates and other media-commodities, developing the media mix and its modes of consumption that are so essential to anime's own commercial success – and survival.

Anime-inspired products allow characters to inhabit fans' everyday lives. Steinberg recalled the success of Astro Boy sticker campaigns, "The Atomu image was suddenly able to accompany young fans in all areas of their lives, always there to remind them of their favorite character and his narrative world."

By purchasing merchandise, fans gained ownership and grew closer to a series. Character goods gave added value to everyday objects. With the addition of a character image or logo, boring commodities like notebooks, pencils and toothbrushes become special. Applicable items like stickers and patches mean fans can customize and synergize anything (Steinberg)

Fans' love for marketable characters proved more profitable than the love for intangible narratives and stories. Since the Astro Boy boom, popular anime characters have come to saturate Japan, inundating all facets of life.

Would "Anime" By Any Other Name Look as Sweet?

To some, anime's popularity and marketing synergy pale in the face of "low quality" animation. Full-animation purists, like the old Toei Studios and Miyazaki, resisted the new wave of Japanese animation. Their features feature the full movement of characters. These studios took honor and pride in smooth, fluid animation. They sought to "produce the 'illusion of life." (Steinberg)

Astro Boy's popularity shocked them all. Astro Boy and its successors flaunted their lack of realism. Animation critic Joji Hayashi contends, "limited-animation does not try to hide from the spectator the fact that it is an unreal image." (Steinberg) Although anime's techniques create an illusion of motion, it does not try to emulate reality as full-animation does.

The debate continues today. Miyazaki and other full-animation purists connect animation to reality. In a recent interview Miyazaki bemoaned the current state of anime. Otaku are ruining the industry, he said, by creating stylized and therefore unrealistic character driven works.

But animation expert Roger Noake counters,

There is a danger in confusing full-animation with good animation. At its best it can be excellent. But if full-animation is used as the norm by which all other animation is judged, this can promote a cruel and narrow attitude (Hu).

Not all full-animation is "good." At times full-animation looks so real it becomes surreal, even unnatural and awkward. In extreme cases like rotoscoping, a technique of tracing live film footage, the resulting movement is so fluid that it can actually be distracting.

Beauty Lies in the Perception of the Beholder

Although limited-animation may not better represent reality, it may better represent our perception of reality: the way humans observe, process and remember information.

Do we notice and process every detail in everyday life? Selective attention theorists say no. "Individuals have a tendency to orient themselves toward, or process information from only one part of the environment with the exclusion of other parts." (Beneli)

In fact, human perception didn't develop to create photographic representations of the surrounding world. Daniel Simmon explains,

The goal of vision isn't to build a photograph…of the world in your mind… The goal of vision is to make sense of the meaning of the world around you."

This quote suggests limited-animation's lack of motion and details eases our understanding of characters, narratives, and themes. Although full-animation mimics reality in detail and fluidity, limited-animation tunes into human perception by focusing on the raw, concentrated meaning of the world around us; albeit fictitious, animated worlds.

The Grand Illusion

But does that even matter? Dismissing any animation does a disservice to the medium. Who says animation has to be fluid? Or realistic? Or entertaining? (Oh right, Miyazaki does.) Animation's greatest strength lies in its lack of rules, versatility and in its ability to tackle an endless variety of subject matter.

When live-action faced technological limits, animation broke the shackles of filming reality. Unlike those films, animation made anything imaginable possible. And when full-animation's limits hindered television production, Tezuka Osamu and Mushi Pro had the insight to create animation by eliminating animation. Their methods for producing cheaper anime at a fast pace became the industry standard and the striking style has gained a fanbase around the world.

Researching this article has proven a double-edged sword. Although I loved learning about the animation process, I will never view anime the same way again. The knowledge has highlighted moments of pull-cels, sectioning and reuse have received highlights. Instead of enjoying the illusion, I notice techniques.

Yet my newfound sensitivity makes little difference; anime's striking style, great characters and cool narratives overcome all. Despite acknowledging the deception, I can't help but enjoy and appreciate it. As Marc Steinberg says, a book, comic or DVD has almost no value as an object: "Value is in the consumption, the enjoyment."