Editor's Note: Happy Pi Day (3-14) everyone!

Not all that different from Fight Club, there's an underground movement of people who just memorize things. Cards, words, stats, and… uh… sorry, I can't quite remember the last thing I was going to say.

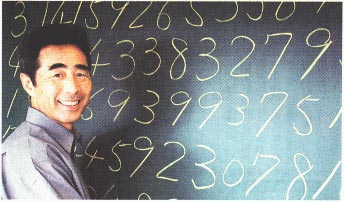

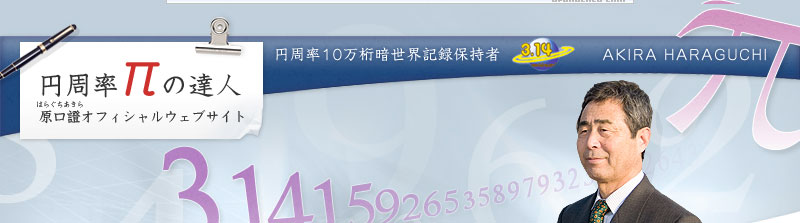

When you look at memory experts, though, there is one man I'd immediately put at the top of that memorization pedestal, and that man is Akira Haraguchi, a retired Japanese engineer born in 1946. As you can probably guess from the title of this article, he also happens to be the person who recited pi to a cool 100,000 digits. Considering that I can recite pi to around… oh I'd say two digits (3.14)… 100,000 is no small feat. Is he some kind of super genius? Is there something special about him? Perhaps, but he says he was not a child prodigy or anything of that nature. He even has a memory of being forced out into the hall at school as a punishment because he couldn't memorize the multiplication tables of one-digit numbers properly. That must be a fun memory for Haraguchi to look back on now.

So what made him undertake this (crazy) task? These two paragraphs from the Japan Times sum it up better than I could:

Interestingly, Haraguchi says his interest in pi has a lot to do with his lifelong quest for eternal truth. Since childhood, he has always wondered why some people — especially those with physical and mental disabilities — suffer. He consulted religion and philosophy books for answers, but in vain. Then he turned to nature, and realized, he said, that nothing in nature — be it leaves, trees or mountain scenery — is linear or square. "I realized that nature is not made of straight lines. . . . And I realized that all things in the universe . . . rotate. Rotation became a key concept for me."

So when he learned that pi is an endless series of numbers with no pattern or repetition, it made perfect sense to him to take it as a symbol of life, he says — adding that he now calls pi memorization "the religion of the universe."

From there he started memorizing. Between 2004 and 2006 he had four main "events" in his memorization life:

- September 2004: Recited Pi up to 54,000 digits.

- December 2004: Recited Pi up to 68,000 digits.

- July 2005: Recited Pi up to 83,431 digits.

- October 2006: Recited Pi up to 100,000 digits.

The 100,000 digit record was the height of his career and done at a Tokyo event where he spent 16.5 hours reciting number after number after number (stopping every few hours to eat delicious onigiri to keep his mind and body in shape). Despite the fact that three out of four of these recitations were done for witnesses, according to the "Pi Ranking List" Haraguchi doesn't even exist. They've sent tapes too, but for some reason Guinness World Records have yet to accept any of them. Maybe they just forgot?

Here's what the "official" Pi Ranking List looks like:

- Lu, Chao (China) – 67,890 Digits

- Chahal, Krishan (India) – 43,000

- Goto, Hiroyuki (Japan) – 42,195

- Tomoyori, Hideaki (Japan) – 40,000

- Mahadevan, Rajan (India) – 31,8111

- Tammet, Daniel (Great Britain) – 22,514

- Thomas, David (Great Britain) – 22,500

- Robinson, William (Great Britain) – 20,220

- Carvello, Creigthon (Great Britain) – 20,013

- Umile, Marc (USA) – 15,314

Like Pi itself, the list goes on and on, and if you'd like to see it you can do so here.

As you can see, nobody is even close to the 100,000 mark that Haraguchi achieved in 2006. Even his other three "unofficial" attempts either come in second or first place on this international list (54,000 digits in September 2004 is the only one that doesn't lay the smackdown on everyone). Whether it shows up on this list or not, there's something remarkable going on here.

Visual Mnemonics

Although the Japanese are known for their rote memorization in schools, memorizing 100,000 digits of pi probably isn't the kind of thing a fairly "normal" guy like Haraguchi should be able to do. It turns out, as one might expect, that he's using a mnemonic method that he developed in order to remember all these digits of pi. This is good news for you and me. It means that with practice we could memorize 100,000 digits of pi too. Well, maybe not 100,000, but 100 digits of pi wouldn't take that much effort if you did it right. The word "right" is the key, though. We memorize things very inefficiently, most of the time. Our brains are pretty bad at remembering digits, times, lists, etc., On the flip side, our brains happen to be really good at memorization when it comes to something visual or sensory affecting. Ever notice how occasionally a random smell will be soooo nostalgic?

When it comes to memorization (and memorizing a lot of things), memory experts tend to focus on the visual. There's a reason why people say "take a trip down memory lane," after all. Here's an example: Say you walk into an unfamiliar room. Maybe it's your friend's bedroom. You're in there for only thirty seconds then leave. Three months later you come back. Chances are, you'll remember a whole lot about that room. You'll remember where the video game controllers are at, where the books are, where the chairs are, so on and so forth. You may not know every detail if you're not looking super carefully, but I bet you would remember 100+ things about that room if you had to quantify what you remembered. If you think about it, that's pretty incredible. It takes how many hours to memorize 50 Japanese vocabulary words? Yet, when you walk into a room you instantly memorize hundreds of details about it? That's just how our brains work. We're very visual about our memories.

There's some data that shows the visual nature of our brains, too. In one experiment in the 1970s, researchers showed participants ten thousand different images in quick succession. Then, they were shown two pictures: One they had seen, and one they hadn't seen. Their job was to point out the one they had seen. Amazingly, they were able to recognize 80% of the photos they had seen. In another study with only 2,500 photos, researchers tested participants by putting two very similar pictures next to each other. With this one they saw a 90% correct rate. If they gathered the participants up again a year later they would probably still have a pretty good recall rate, too.

So as you can see, mnemonics tend to be visual for a reason. On top of this, you're also encouraged to use other senses as well. You're supposed to smell the things in your stories. Touch them. Taste them. It's a multi-sensory experience, and the more you get involved the more likely you'll be able to remember something. That's why there are various kanji learning methods that use stories to help you to remember the kanji's meaning and reading. There's a reason why people who use mnemonics tend to learn kanji a whole lot faster than those who do not. It gives you more triggers to pull the memory out of your head, because as we see with the picture experiment, we don't have trouble putting things into our brain, we just have trouble pulling things out.

The Major Mnemonic System

So Akira Haraguchi uses a mnemonic method to memorize pi. What could he possibly use that lets him memorize 100,000 digits?

First we have to understand that there are different mnemonic methods for different things. Haraguchi used a modified version of the "Major Method," which Wikipedia explains the following way:

The system works by converting numbers into consonant sounds, then into words by adding vowels. The system works on the principle that images can be remembered more easily than numbers.

Just going down the numbers 0 through 9 we can see what consonants are associated with what number.

0 = s, z 1 = t, d 2 = n 3 = m 4 = r 5 = l 6 = j, sh, soft g, soft ch 7 = k, g 8 = f, v 9 = p, b unassigned = vowels, w, h, y, x

The idea is that you take the number you want to learn (for example 701) and then apply the correct letters to it, spelling out a word. They don't have to be the correct spelling, but they do have to have the correct pronunciation. With the example 701, you can use g + s + t. Put some vowels and other unassigned consonants in there and you have "ghost." So instead of having to remember the numbers 701 you can just remember the idea, or even the image, of a "ghost" which is a whole lot easier to recall later on. Some more examples:

15 = TaiL 927 = PiNK

There are other more complicated mnemonic methods for learning numbers, but this is probably one of the most simple. For example, if you can associate two numbers at a time to something, you're going to be able to learn digits twice as fast. Some people have expanded that up to three or four numbers (or more) at a time too. Alternatively, you can associate images (starfishes, beer, frogs, etc.) to numbers as well, then combine them to make stories. The ways in which you can memorize numbers goes on and on.

Akira Haraguchi's Mnemonic Method

Of course, Akira Haraguchi had his own method for memorizing so many digits of Pi and it has a very Japanese spin. In fact, you'll need to know hiragana to use his method and know quite a bit of Japanese as well, should you want to utilize it. I'd like to even think that the Japanese language is more suitable to learn digits just because the way it's set up. With the major system, you have to add in vowels and other unassigned letters. With this Japanese version, pretty much all the "letters" have vowels already attached. That takes out a lot of the guess work and makes things much more straightforward.

For example:

0 → お、 ら、 り、 る、 れ、 ろ、 を、 おん

1 → あ、 い、 う、 え、 ひ、 び、 ぴ、 あん、 ひゃ、 ひゃん、 びゃ、 びゃん

etc…

The list keeps going like this, and each number has a set of kana associated with it. In the beginning, I'm sure he had to just spend time memorizing what is associated with what, but that's just a drop in the bucket compared to what he ended up doing with it. With practice, he was able to come to a point where he "simultaneously interprets" these sounds into numbers, so what do the sounds do?

Remember how we talked about images and stories earlier? He takes each digit of pi and turns it into a story. Basically, he just has to choose sounds that will come together to make words that make sense. Then these words have to come together again to make a story. Our mind is much better at remembering stories compared to numbers, so by remembering the story (much easier) he is able to translate that into the digits of pi. One example on a Japan Times article revealed what the first 15 digits of pi were (3.14159265358979), aka…

- 妻子異国に 婿さん 怖くなかった。

- "The wife and children have gone abroad; the husband is not scared."

If you can memorize that sentence you can memorize the first 15 digits of pi. Of course, you have to put the work in to get your associations going, but with practice anyone could do it, even you.