Ghost stories have been big in Japan for about as long as there's been Japanese literature. When they were first written down in the Heian period, at the same time as the classic Tale of Genji, there were enough to fill a 33-volume collection. When the first printing press appeared in Japan around 1600, ghost stories were among the best-sellers.

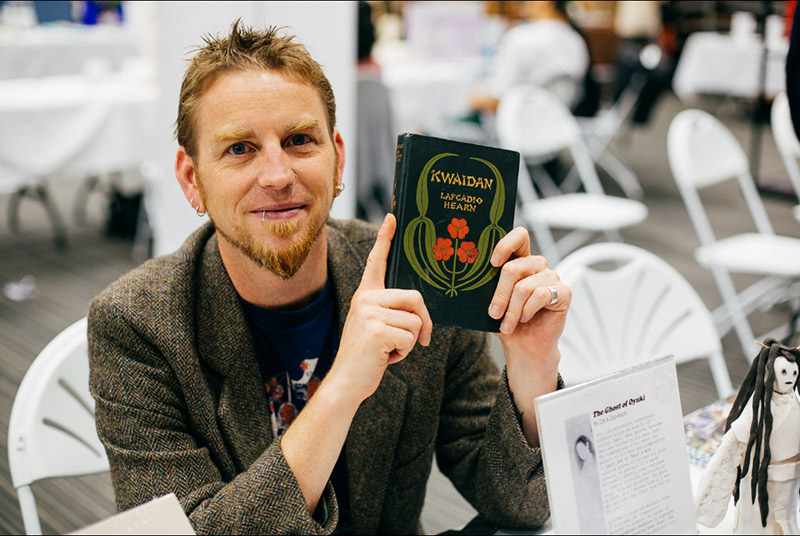

But when it comes to writing about these stories, oddly, a Westerner has dominated this arena. If you go to a Japanese bookstore and ask for a book about ghosts, they'll hand you the work of Lafcadio Hearn, renowned as the first major interpreter of Japan to the West after it opened to the outside world in the nineteenth century, and author of books including Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things and In Ghostly Japan.

Today, a modern day Lafcadio Hearn is picking up this ghostly torch. Zack Davisson is the author, translator, and folklorist following in Hearn's footsteps. His book, Yūrei: The Japanese Ghost, is coming out in October. Tofugu got the chance to sit down with him and discuss Japanese ghosts, translation, and working for the godfather of horror manga, Mizuki Shigeru.

Q. Your book is based on your blog, which is called Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai. Can you explain the name of the blog?

Actually, both the blog and the book are based off my Master's thesis Yūrei: A Study across Time and Media. I did the thesis first at the University of Sheffield, then the blog, and now the book!

The name Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai comes from a parlor game that was popular in Edo period Japan. It translates somewhat poorly as "A Gathering of a Telling of 100 Tales of Kaidan". The basic way to play was to invite a bunch of friends over, light a hundred candles in a circle, then take turns telling spooky stories. You extinguished one candle with each tale, and the room got gradually dimmer. The tension built. With the final candle, the room was plunged into total darkness. Something was said to be waiting in the dark—the game was also a summoning ritual, you see. In practice, most people wimped out before the final candle. Most games of hyakumonogatari kaidankai ended with the 99th story.

It seemed like the perfect name when I started the blog—basically I was using it as a dumping ground for stories I had translated for my Master's, and that fit the hyakumonogatari kaidankai theme. I've been told numerous times I should have named the blog something else—hyakumonogatari.com is hard to say and hard to remember, especially if you don't speak Japanese. At the time I didn't give it much thought: I honestly didn't think anyone else would be reading. Now it's too late, and I love the name so I am sticking with it!

Q. As you describe it, there were often no plots to these ghost stories, just a description of a weird thing that happened that did not "stink of literature." So, basically Japanese people have always liked reality TV?

Ha! That is one way of looking at it! But yeah, telling a "true" story, something that actually happened to you, was much more exciting. That's still true. No one sits around the campfire and swaps movie synopses. You want personal encounters to really freak people out.

And the stories were often short. After I translate them, there is sometimes no more than a paragraph or two, with little plot and lots of variations on the same stories. Like just this weekend, my wife and I were in the woods and we saw a strange flash in the sky. We would tell that at a local gathering, and then the story would pass from mouth-to-mouth and game-to-game, with details getting altered, locations changed, etc… Like modern urban legends.

Q. You say in your book that it's important to know about Japanese ghosts if you're interested in Japanese popular culture. Why is that?

It's an important aspect of Japanese culture and history—more important than most people realize. After all, Japan is the most haunted country on earth. Yūrei are deeply bound into the country's customs, religion, and entertainment. There is almost no aspect of Japanese culture not touched in some way by ghosts.

Even if you just want to watch some cool horror flicks or anime, or play some games—everything makes more sense when you understand yūrei; when you know the backstory behind the movie monster costume of white kimono, white face, and black hair.

After all, imagine watching a vampire flick without knowing what a vampire was. You wouldn't have the slightest idea why these dead people sprouted pointed teeth and bit people, or why the heroes kept stabbing wood into them. You need context.

Q. When and how did the consistent description of yūrei begin? You say in your book that it was created as recently as the Edo period, during a renaissance of spooky tales.

In Japan's prehistory, yūrei were invisible, more like forces of nature without personification. Things changed during the Heian period and contact with China. Yūrei became indistinguishable from human beings. They could even get married and bear children after death. You can tell stories from the Heian period because they usually have a twist ending of someone being revealed as a yūrei. Probably the most famous of this kind is Botan Dōrō, where a man takes a woman to bed, and finds out later he was sleeping with a corpse.

Then came the Warring States period, which didn't produce a lot of yūrei tales—people were too busy worrying about being killed for real to bother about ghost stories and horror. But they made up for it in the Edo period.

During the peace of the Edo period, Japan rediscovered its love for ghosts and the weird. There was a kaidan renaissance, and the first of Japan's yokai booms where the country became obsessed with the supernatural. That classic look of the yūrei—the white kimono, white face, and black hair, comes from the Edo period kaidan renaissance. It relates directly back to a painting from1750 by the artist Maruyama Okyo, who had a vision one day of his dead love Oyuki. He painted her picture—called The Ghost of Oyuki—which became the template for yūrei that you still see today.

Q. If people have seen even one J-horror flick, they've seen the ghost with long hair. What the heck is the deal with the long hair?

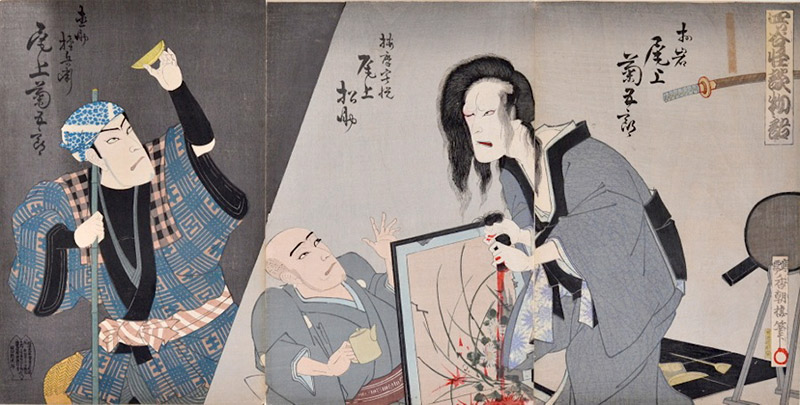

Hair—especially woman's hair—was always thought to possess supernatural powers. Lafcadio Hearn wrote about it in his first Japan book Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. But Kabuki theater is really behind the craziness of hair. Kabuki loves extravagant, wild special effects, and would do all sorts of things with hair. Stage hands would hide under the floor boards and push up hair through the bottom to make it look like yūrei characters were swimming in oceans of hair. Movies are visual, like kabuki, so they picked up that effect and ran with it.

Q. One thing I was surprised to learn from your book was the role of kabuki, where ghost stories were big, and more gore was a plus. To be honest, I always thought of kabuki as one of those tedious classical Japanese entertainments that are only of interest to specialists. But you say it was actually theater for the masses. Tell us a little about ghosts in kabuki.

Oh yeah, Kabuki was completely lowbrow mass entertainment. During the Edo period, kabuki would have been the equivalent of Saw and Friday the 13th slasher flicks, full of blood and guts and cheap thrills. Kabuki also took those snippets of tales from hyakumonogatari kaidankai and sewed them together into legitimate stories. Kabuki writers introduced plot lines and structure and relationships. But it was always with an eye for thrills. The plays kept getting gorier and gorier until eventually the government had to step in and establish some limits.

It's weird how that works. In his time, Shakespeare was lowbrow mass entertainment too. The theater was a place for laborers to let off some steam. Now both kabuki and Shakespeare are considered high art, something to be studied and mastered. It makes me wonder what people will think about slasher flicks five hundred years from now. Will we have Jason scholars debating the finer points of the Friday the 13th franchise?

Q. In your book you mention one significant difference between Japanese and western ghost lore: In the west it takes a lot to become a ghost – you need a really good reason to haunt. But in Japan, it's harder to cross over into death, so even just forgetting to feed the cat is enough. Why?

Well, forgetting to feed the cat might have been artistic license on my part, but the rest is true. Humans aren't born easily; we need some assistance coming into the world. In Japan, they believe you equally need some assistance getting out. Dying is not easy.

This belief has manifested in several different ways across Japanese history. From the Heian to the Edo periods, it sometimes involved professional "death midwives" called zenchishiki that helped people pass over to death. The belief was that whatever was your last thought at your moment of death, that is what you would become. So the zenchishiki tried to get people to concentrate on Buddha, and to free their minds of attachments to life. In modern Japan, the belief involves a complicated funeral system of ritual and death anniversaries that can last up to a hundred years before a soul is well and truly settled in the afterlife.

Ritual plays a huge part in things. Anytime there is a series of mass deaths someone will perform a ritual to help ease their passage. At the end of WWII, Nambara Shigeru led The Ceremony to Console the Souls of the Battle Dead and Those Who Died at their Posts in an attempt to pacify the souls of those who died during the war. He was worried that, with Japan's surrender, the yūrei would feel angry that they had died for nothing.

Q. This book is definitely not all about old fairy tales. You say the dead are very powerful in Japan – and very present, even now. Talk a little about the present effects of these beliefs, which might be seen when visiting Japan or in the popular culture, but are easy to miss.

This was right in my face when I landed in Japan. I arrived right when the country was gearing up for Obon—the Festival of the Dead. That is one of Japan's most important holidays, with many people taking the entire week off to care for the dead. They go to family gravesites and wash them, they set out food and light candles for the dead so they can find their way home. It's something completely confusing if you don't understand Japan's relationship with yūrei.

Aside from the big production of Obon, the dead are present in a million little ways. Many homes have a butsudan in the living room, where the recently dead are said to reside. If you see the little Jizo statues all over the place those are usually prayers for dead children. Houses and apartments that are known to be haunted must be officially listed as such. And yūrei who have not been properly tended to is a constant worry. After the 2011 tsunami, you heard all sorts of stories of yūrei. Buddhist priests in the area set up little pop-up exorcism huts to pacify the souls of those killed. It is taken very seriously.

The deeper you get into Japanese culture, the more powerful and personal the connection to yūrei becomes. As an example, when I became serious about my girlfriend in Japan (now my wife), she said I would have to make a formal presentation to her father, and ask for permission to marry her. It didn't matter that her father was long dead. I paid a formal visit to his grave to express my intentions about his daughter, and asked his blessing.

Q. I have a few questions about details of language, since we are into that here at Tofugu –

Ohhh … that's going to be tricky! But I'll do my best!

Q. Obake or yūrei?

This is the tough one. Basically, obake means changing thing and yūrei translates as dim spirit. But that doesn't really tell you anything. Over the years the nuances of the words have changed, and ask a hundred people and you'll get a hundred answers about what constitutes an obake and what is a yūrei. For example, in the Meiji period, folklorist Yanagita Kunio said that obake haunt places, while yūrei haunt people. Other folklorists say that obake is more synonymous with yokai and can mean monsters and other phenomenon, while yūrei are specifically the souls of dead humans.

In practice, most Japanese people don't split hairs over definitions. Freak them out with a ghost, and they are just as likely to shout "obake!" as "yūrei!" Either word does the trick.

Q. Kaidan?

This is my favorite, and a famously tricky word to translate. The most literal possible interpretation of kaidan would be something like "a discussion or passing down of tales of the weird, strange or mysterious". Personally, I prefer to either use the word as it stands, kaidan, or if I must put it into English I take a page from Irish author Sheridan Le Fanu who called his stories of the supernatural and sublime "weird tales".

"Weird Tales" invokes both the nostalgia and the nuance of the type of story a reader can expect from kaidan.

Q. The stories in your book often end with "So they say." Is that just a kaidan thing or a general folktale ending?

That is specific to the 12th century book Konjaku Monogatarishū, which was one of the first important collections of kaidan storytelling. Basically it was a little tagline at the end of each story assuring the reader that it was a true tale, and not something made up.

People translate it in various ways, like "So I heard it said, and so I am relating it to you." I prefer the simpler "So they say" version, which makes a nice little punctuation to the story.

Q. Last question about the book: Is it appearing in Japanese? I'd like to think that from now on the booksellers will now be recommending both Lafcadio Hearn and you.

That would be cool! I honestly don't know about translating the book into other languages. It really depends on how successful the English version is first. And I would love someone to recommend my book and Hearn's the same breath. I deeply admire Lafcadio Hearn, and am a dedicated fan of his work!

Q. Okay, enough with the ghosts, let's talk about you: How did you get interested in Japan and in yūrei?

My Japan interest started when I was a little kid—I think about 9 years old—and my mother took me to see Akira Kurosawa's flick Seven Samurai at the local art theater. I thought it was the most amazing thing I had ever seen. It's a little embarrassing, but in my 4th grade class photo I'm wearing a shirt that says "Japan" written in kanji. That was in 1981, I think.

My interest in yūrei comes from the same time. I've always loved the supernatural and fairy tales. My mother bought me this book series from TimeLife called Enchanted Worlds that was all about world folklore and monsters. The book on ghosts had a story called "The Wife's Revenge" which was the story of Oiwa from Yotsuya Kaidan.

It wasn't until I moved to Japan that my yūrei interest became full-blown. The more I learned, the more I wanted to know.

Q. You're translating Mizuki Shigeru's huge Showa: A History of Japan, published by Drawn and Quarterly, two of which have appeared and the next one is coming out in November. How did this project come about?

There's actually four volumes in the series. The last volume, Showa 1953-1989: A History of Japan, is scheduled to come out April 2015.

And I don't know the details about how the project came about, other than how I got involved. I LOVE Mizuki Shigeru's comics. My wife introduced me to them in Japan, and I quickly became his number one fan and English-language apostle. I had been trying for years to do English translations of his comics. I contacted several publishers, but most either thought Mizuki was too weird for an American audience, or they were interested but couldn't get the rights.

When I saw Drawn & Quarterly had the license to his works, I basically just wrote them a letter talking about my passion for Mizuki's work and how much I wanted to translate his comics. I offered to do a test translation to prove I was up for it, and they agreed to that and then hired me based on that.

Q. I'm curious why, of all his work, they chose to publish this – especially because, to be honest, I skip all the battle scenes looking for the next appearance of Nezumi Otoko, which is the sort of stuff he is more known for.

Again, I don't honestly know. I can guess. Partly, I imagine it is because of the lack of familiarity with Mizuki's work in the US. Inside of Japan he is a god—he is Walt Disney-level famous, better known even than Hayao Miyazaki. Internationally, he is incredibly famous as well. His complete works have been translated into Spanish, French, Italian, German, and most of the Asian languages. But in English .. nothing. Even people obsessed with Japanese culture have this dead spot where Mizuki is concerned.

So I think from that standpoint his WWII comics, like Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths and Showa: A History of Japan, were safer bets. Comics about WWII have a built in recognition factor, especially when you have the human element where they are created by someone who actually fought in the war.

After all, it is much easier to pitch "Comic book autobiography about WWII by a Japanese soldier who fought in the South Pacific and lost his arm" than "Weird stories about Japanese monsters you have never heard of written and drawn by some old dude you have never heard of."

At the time I thought it was a strange way to go, but now I see it was for the best. Onward to Our Noble Deaths raised Mizuki's profile in the West and opened the doors for his other works.

Also, Mizuki is actively involved in what books he allows to be translated or not. He cares very much about his reputation as a scholar and an artist, and wants to be sure that a variety of his work is being showcased. He doesn't want people to just cherry pick the fun stuff and overlook the things that he is really proud of, the things that might be a little more difficult to grasp.

Personally, I would love to translate his adaptation of Tono Monogatari. That is one of his most brilliant works. And his adaptation of Lovecraft's The Dunwich Horror, which would just be a hell of a lot of fun. But while I can make suggestions, it isn't really my call.

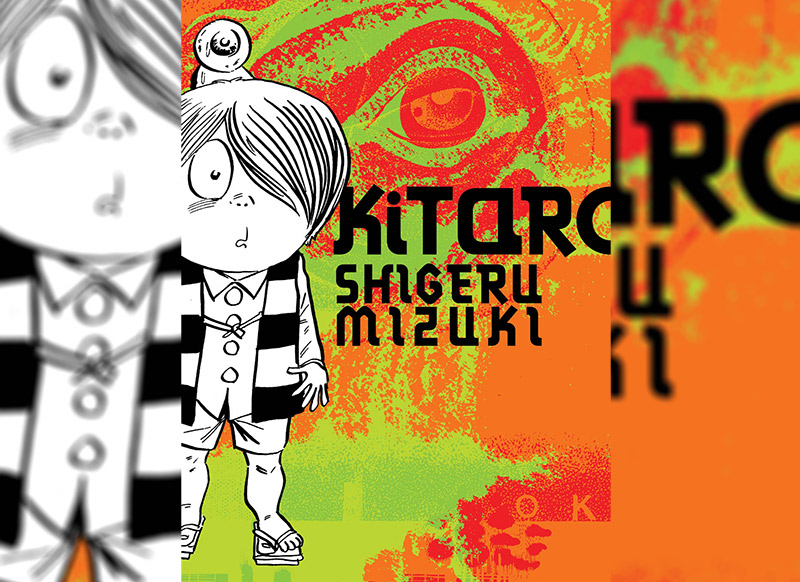

Q. You also contributed the yokai glossary to the translation of Kitaro that Drawn and Quarterly published, and I understand you also did some editing and made some important contributions regarding the yokai names and sound effects?

Yep. Kitaro was already translated by the time I came on board, but I did some pick-up work, mainly the sound effects and such. Those are actually some of the most difficult things to translate. Japanese and English useonomatopoeia very differently, and there is no easy way to switch one for the other. Fortunately, I have a lifetime background in reading American comics so I have a mental library that I can pull from. The best part was coming up with the monster's roar. I wanted something distinctive, so I wrote out a bunch of monster roars to see which one looked the best.

And I did have a hand in the names. The translation gave the yokai English names, so things like "Rat Man" instead of Nezumi Otoko, and "Sand-Throwing Hag" instead of "Sunakake Baba." I was adamant that the yokai names should be kept in Japanese. I used the argument that no one calls Pikachu "Flash Mouse." Even small kids deal with Japanese names just fine.

In the end that's how the Yokai Glossary came about. I won my argument, and wrote up the glossary at the end to explain all the different monsters. That piece of Kitaro isn't a translation, it's all me. And it was SO fun to do!

Q. Of course the big crucial question about Kitaro: Do you know if there is going to be more? Or more of his other work that isn't war related? D&Q also published his Onward Toward Our Noble Deaths – they seem to be obsessed with war stories. I want to see yokai!

The next book up is Hitler, so more war stories. And give the war stories a chance! They are actually very cool! I learned a lot translating Showa: A History of Japan—it's important history that shouldn't be forgotten. I'll never forget what my wife said when she was reading it while I was working on it: "I finally understand why China hates Japan … "

But after Hitler … I can't really spill the beans yet, but I will say that sometimes we all get exactly what we wanted. Look forward to that.

Q. Probably your most unexpected translation project: Mizuki is actually on Twitter and you translate some of his tweets. How did this get started? Have you ever communicated with him directly?

I just do that for fun—it isn't an official thing. I think Mizuki is such a fascinating individual, so I like to share him with the English-speaking world. His twitter account is great. It's almost entirely about what Mizuki is eating. Here you have one of the most famous and respected men in the entire country, and he shares Twitter pics of himself stuffing his face with a McDonald's hamburger. How could you not want to share that?

And I have met Mizuki only once, at the World Yokai Conference in Kyoto. And that was very brief. No one really speaks to him directly, you usually go through his son, or with a contact at Mizuki Productions. I wrote him a letter when I started work on Showa about how honored I was to be translating his work. He didn't answer, but I didn't expect him to. He is 92 years old, after all!

Q. What else are you working on that our readers would be excited about?

Oh, lots! I just finished translating two comics by Satoshi Kon for Dark Horse, OPUS and Seraphim, which he worked on with Mamoru Oshii. Then the comic Wayward just came out from Image, which has met with a phenomenal response. I'm seriously blown away by how excited everyone is. I work on Wayward with Jim Zub, Steve Cummings, John Rauch, and Marshall Dillon, writing back-up essays for Wayward and doing in-depth Yokai Files for the monsters. If you are looking for yokai, that's something you can't miss. The pitch is "Buffy the Vampire Slayer in Japan" but that's just the surface.

Then I have Hitler to get started on, and after that a few more secret things I can't talk about yet, both in comics and books. I have a Lafcadio Hearn project I am working on, and something cool with an artist friend that we have been rolling around together. And maybe something with monster cats. But we'll see.