Here at Tofugu we get countless emails from people who want to be Japanese translators. While my own experiences are limited, I thought there would be no better person to ask than my former Japanese literature professor and university advisor, Dr. Susanna Fessler. She was nice enough to hop on Skype and answer all of my questions regarding literary and freelance translation, and interpretation. This is the written version of that conversation, so please pardon the casual tone and enjoy this unfiltered interview!

Q. What is your name and where do you currently work?

My name is Susanna Fessler and I'm a professor in the East Asian Studies Department at the University at Albany, I've been there for twenty years.

Q. What kind of translation work have you done?

What I do is largely literary translation. I have done commercial, or what they call technical translation, it's been a very long time since I've done it. I did it back when I was in graduate school on sort of a freelance basis. I can't remember how many jobs I had – a few, I was in the midwest. And I also spent a summer being a technical translator in a car parts factory in Ohio for a subsidiary of Honda. They were just setting up production and they had a staff of about a dozen Japanese management and about a dozen Americans and they had a huge problem because the Japanese didn't really speak English and the Americans didn't really speak Japanese and they were trying to get their factory set up so they hired me to come in and both interpret and translate.

Q. How many years have you been working in the world of translation?

I guess all told, about twenty-five years, on and off since grad school.

Q. How did you become interested in being a translator?

Well, when I was doing technical translation I was in it for the money, I'll just be perfectly honest about that (laughs). Technical translation is not something – I don't know anybody who does it because they find it edifying – but it pays well. And what often happens is you'll find that technical translators do that to put food on the table, but then they'll also be really interested in literary translation because it's the literary translation that is edifying.

Now in my case, I did the technical translation to make the money, and since I have pretty much stopped doing that. Sometimes I'll get a query through the department or something but usually I'm not interested, or I can't do it cause there's a time conflict or something like that. So I just pass it on. But you'll also find, if you talk to a lot of people who do translation, that in the world of,literary translation almost everyone, with maybe the exception of one or two people in Japanese to English translation, is not really a professional translator. They are probably like me; they are professors. They do translation on the side, so to speak. In academia, it depends on the institution but in a lot of places they kind of frown upon translation as research activity. They'll say, Oh it doesn't "count" – count toward the research portfolio that you have to build in order to get promoted and to get tenure. And so what pattern you'll find is that a lot of literary translators start out as professors but they don't really do literary translation until after they've gotten tenure. At that point they're safe, that job is safe, and they can go do that translation and it's not going to be held against them when they come up for promotion further on. And I very much fit that pattern.

So my first two books were monographs, and then I got tenure, and then I remember chatting with another professor, who's been my mentor since I came here, and I said, you know I have this opportunity to do this literary translation, I really want to do it, but I know everyone says, oh translation doesn't count, but he said don't worry about it, you've got tenure now you can do whatever the hell you wanna do (laughs). So that's what I did, you know, I did that translation. Then that led to the next project, which is another translation, which I've just finished, and I'm not sure what the next project's going to be, I'm kind of torn. I was asked if I wanted to do another translation and I'm just not sure. Maybe that'll be like, the project after the next project.

Q. What was the very first thing you translated?

That goes way way way far back. I translated a short story when I was a sophomore in college. It was a story by Enchi Fumiko and the title of it is "Korosu" as in the verb "to kill" and it was published in this rinky dink little publication that the East Asian Studies Department at Oberlin College puts out called Ao Tung. So that was my sophomore year and in a way it was kind of like what you were doing last semester. It was my first foray into anything like that, it was an independent study, they call it something different at Oberlin, but that's what it was. And so I worked with a professor and you know, I picked out the short story, and then I spent the semester effectively with Nelson's chained to my ankle (laughs) and just sat there and, you know, worked and worked and worked at it.

Q. What would you say someone needs to do to professionally translate literature? Do they have to become a professor to do it? Or is there a different path?

You know there isn't something you have to do, there is that standard path that I just described, but there are some people who are not professors who translate. They're few and far between, usually they're independently wealthy so they don't have to worry about it, right? Obviously, you have to develop the language skills and you have to develop the research skills. You have to be an excellent writer in your own language. If you're doing Japanese to English, your English has to be really good. There's a website – I was thinking about this as I was madly peddling home today – that I have passed onto a couple of different people and I can't remember if I passed it onto you. It's called something like, So You Want To Be a Translator. It's written as part of a blog by a woman who does Japanese – English translation. I don't think it would be too hard to find if you do some judicious googling. And I thought she had some really good advice, she had like four or five points about what you need to do, and I've already reiterated three of those I think, in terms of developing research skills and language skills, and I think one of the other things she points out is that when you translate something, you become an expert in it. Especially when you're doing technical translation. So you actually have to learn about that thing. That really rang true to me too when I was working in the car parts factory, that was a factory that produced rack and pinion steering components. About which I knew nothing, absolutely nothing, right? I didn't know the English for half the things in that factory, but I learned really fast. And so later on I knew a lot more about that production process. Or, I did a small job translating some newspaper articles from the industrial glass world. And I didn't know anything about industrial glass production, but I learned a lot doing that too.

So for technical translation you do have to become that expert, but you know in literary translation you have to become an expert too, in that you have to find the voice of the author, and try and reproduce that. So you create a specific persona, or if it's a work of fiction where you have dialogue and things like that, then you know the different characters have to develop that voice. You can't just do a sort of mechanical kind of translation, it doesn't really work very well.

There is at least one training road that one can take. That list of people that I contacted for you were all part of the British Centre for Literary Translation. I don't think there's anything like that in the United States. It's located at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, in the UK. And every summer they run a workshop where they get people together who are interested in literary translation and they have different language groups each year. The year I went, which was about five years ago, there were, I think, six different groups and Japanese was one of them. In each group there were about ten participants, and in addition to the ten participants, this is the really cool part, they bring in contemporary authors. They have the author there, and they have someone who has worked with the author as a literary translator, and they run the sessions. So for a week, all day, everyday, you're sitting in this room with a contemporary author and a bunch of other translators, and looking really closely at various passages that that author has written and deciding how it would be translated well into the target language, and in my case it was English.

The author that was there my year was Tawada Yōko, whose work I'm not a big fan of, I gotta say, but she is a very famous writer. And I met some really cool people, and had some fascinating conversations, and got to see other people's methods and learning how to translate, or doing the process of translation. One of the things I learned that week was that there isn't one method that's right and we all have our different approaches. For me, it's kind of, I don't know what the right word is, it's kind of organic. I do it sentence by sentence, I read a whole sentence, and I sort of turn it around in my brain or my gut, and then spit something out. Other people would mull over bits and pieces of sentences and then put them together. It really differed. And then we had all kinds of discussions about finding that voice, what I was saying earlier.

There were things I hadn't anticipated, like in that room we had people from New Zealand, and the UK, and Canada, and the United States, and India, and we all had our own idea of what English should be. So what sounded natural to one person didn't sound natural to the other one, and then all kinds of fascinating things came out of that session. So for example, I can't remember if I told you this story or not, there was a passage where there was a noun, and of course in Japanese it's just a noun, it's not singular or plural, but in English we had to make that decision – whether it was singular or plural, and it made all the difference in the world. It was one of those discussions that could have gone on forever, except that the author was sitting right there! She said, "Oh that's an interesting questions I never thought about it that. Like mm, what if I made it this way-" No no no, you can't change your mind you have to just tell us what you intended (laughs).

So anyway, to my knowledge thats one of the few actual training places that one can learn literary translation. I have noticed the phenomenon of courses at the university level being taught on translation increasingly in the world and I have no idea how that works, because they're not language specific. I can't imagine how I would teach that class. I know people are interested in the topic, but I think it has to be language specific, and it would really have to be a very high level course to fly, I think. You know, you can't have people who are in first year language or second year language struggling with texts.

Q. So what does a recent grad do to become a translator? You've just graduated and you have all this language knowledge that's kind of there, how do you get where you need to be?

Well if what you want to do it be a literary translator, then you go participate in the BCLT thing in the summer maybe (laughs). And if that's all you want to do then, either you're going to have to live hand and mouth, or you have to be independently wealthy for a very long time before you can get your foot in the door. Because in the literary world most publishers these days are not interested in publishing older stuff, they only want to publish new stuff. So I can't say, oh I just discovered this new novel, or this novel by Natsume Sōseki that nobody knew existed and let's publish it. People would say, forget it man, the guy died in 1916, who cares? Even though he was one of the great writers of his generation.

For the most part you're working with authors who have current contracts with publishers, and so you have to work with the publisher and the author. So the authors get a say in who they want to translate their work and sometimes that goes really well and sometimes it just doesn't. And the more famous the author is, usually the more cantankerous they are, you know, they can be really picky. If there is somebody who isn't really well known, then they're probably going to be more flexible.

Sometimes presses can be friendly and sometimes they can just be kinda standoffish. Most of the presses that do literary translations are university presses. And so if you're competing in that pool, you're competing with professors. There are a few presses, like Kodansha has kind of pulled out of the game, but for a long time Kodansha International was sort of one of the key players, Tuttle, obviously, is also still there, does a lot of translation. But they often let stuff fall out of print, and then it might just die a quiet death.

I work with a publisher – it's a one man gig – so there's one person working in the office and he does most everything. He lives in Fukuoka, and his love is books, and so he just wants more stuff to be translated. So he's got a nice website and he'll say if you're interested in translating they actually have a process that you can go through. They have an application if you're interested in publishing with them, and they will ask you to pick one of, I think it's ten different things they have on their website to translate, and send it in as a sample. If they think you're competent and there's hope there, then you can start talking with them about it.

The guy's name is Edward Lipsett. I don't know how Edward deals with current authors. In my case, the guy I translate is dead, and has been dead for more than fifty years, so everything is public domain, we don't have to worry about copyright or anything like that. But when you're working with more current authors, then that's where the publisher has to get involved. But Edward, I think he tries to contact the authors and says, you know we have somebody who's interested in translating your work, would you be interested, or he talks to the publishers of the original Japanese and then tries to get them onboard. So there's a big negotiation process, but you kind of have to, as the translator yourself, you have to first show that you're competent, that you have something to offer, and getting to that point isn't super easy.

Now, how do you get to that point? One way is by doing technical translation, and getting comfortable with that process. How do you do that? Well, it's like looking for any job. You have to send a resume out to a whole bunch of different places. It's like opening the phone book and looking under translation, because most technical translation is done through an intermediary, middle-man party. So Company A needs a document translated, they contact the translation office, and then the translation office farms that out to the appropriate person. So it's never a full time job, where you get a salary. Unless you're one of the very few people who does it full time, for say, Toyota is always the example we use, it's not only Toyota, but you know huge companies like that actually do employ a few people full time. But often those people they employ full time are specialized, like they do law, or something like that. I would never take a law job. It's too scary. I don't know that vocabulary and I can't learn it fast enough to be safe. Like, I don't want to expose somebody to a lawsuit (laughs).

Q. So if someone wanted to work for one of those big companies, they should definitely have some kind of specialization. Like if you want to work for an automotive company you should know about that? Or medicine, etc.?

Right, so that's one way to get your foot in that door. Talking to some of the people at the BCLT event who actually have worked for Toyota in the past, they say that what often happens is you simply do a couple jobs, a couple freelance jobs, and they really like your work, and so then you're their go to person, and the middleman maybe gets cut out or something like that. But it takes a long time to be that go to person.

And the competition is, well Japanese to English not as great as lots of other languages, but it's still there. One of the problems with translation, if you move out of the sort of musty world that I'm in and into stuff like video games and manga and anime, is that there is a large crowd of people out there who are willing, and who do, translate game scripts and web pages and all those kinds of things for free, for fun. And you know, you can't compete with free when you're talking about what you're going to charge for something. So that's why I keep saying it's just not lucrative. I think in total I've made like, maybe $150 from my translation (laughs), from the book that I published in 2009. And I'll probably make about that much money from the one that I'm publishing right now. So I just do it because I enjoy it, and it's a fun, fascinating challenge, and it dovetails with my research.

Q. So it really has to be something that you're passionate about, that you want to do because you want to do it, and not, "I want to be rich, I'm going to translate," that's not going to work out for you?

I don't think anybody gets rich doing it. At all. I'm curious, so for example, Jay Rubin, who is now retired, who's my daisempai, if you will. He had the same advisor in graduate school as I did, he was the first generation and I was the last generation, We both worked under McClellan, and McClellen was, you know, one of these demigods of translation. So a lot of the students that he produced then went on to do translation. So Jay did a number of different translations and now in his glorious retirement, is one of the go to people for translations of Murakami Haruki. So Murakami Haruki has two translators and Jay is one of them. I'm not sure how much money he makes on that. I don't think he does it for the money, I'm sure he has a nice pension (laughs). But I'm sure he's making more, because Murakami Haruki, I'm sure he's making more than I am. No question about that.

Yeah, if there's a name that everyone knows now, it's Murakami Haruki.

Yeah, exactly, well those books sell. I mean the reason I don't make money is because my books don't sell. Quite literally every year, maybe two or three copies sell, and that's okay, I don't care. But you know, I don't depend on it to make money, that's for sure.

I should also say, the cousin of translation is interpreting.

Q. Have you ever done interpreting, or do you stay away from it?

For the most part, I stay away from it, but at the car parts factory I did it. But it was exhausting, it was absolutely exhausting. Translating I can sit and do all day, I mean I get tired, but the mental work involved in interpreting, especially because I was a first year graduate student, and at that point I had been studying Japanese for six years, on and off, and there was just a ton of stuff that I didn't know. So it was really very nervous making too. There was a lot of zangyō because they were just setting up everything, you know. And inevitably, half the time you ran overtime. And it was an hour commute one way, in summer, in a car that had no air conditioning. It's the one time in my life when I've come close to falling asleep at the wheel.

But after three months I was so glad that it was ending. I was just exhausted. I wanted to go back to school and do something different. I can't imagine interpreting for a long period of time, unless you were raised bilingually. It's just really hard.

Q. What exactly did you do? Did you follow some people around and help them talk to each other?

Yeah, basically. Like I said, they were setting up the production line, so I would go and interpret for, usually it was the management, who was explaining to the Americans what needed to be done. Or it was an assembly line and they were doing it according to this sort of long standing Japanese tradition where you train everybody for every station, so that if someone's out sick one day, production doesn't stop. So they had to train all the Americans in all the different stations. Like okay, today we're doing chrome plating, or whatever.

So there was stuff like that, and then I would kind of follow people around. One day we had someone come, an American subcontractor who needed to check out some of the air conditioning units that are on the roof of the factory, it was a flat roof, right? So the management was really funny, it was almost all men in this factory, there were like two women in the office, and then everybody else was male. And then there was me. They realized that they needed help with this and they said well, we're not going to ask you to climb up on the roof and I said why not? I'm not afraid of heights (laughs). And so I just followed them up the ladder, and you know, did whatever I could do to explain things.

You're just going to have to be intrepid about it, and say okay, I'll take this challenge or that challenge. But they were nice, they realized that I had my limitations as somebody who'd only studied the language for six years, but my price was right. I was only charging – this was 1988 – I was only charging $10/hr, well 10 to 15, it was cheap compared to anybody else. I think they felt like they were getting their money's worth, and I felt like they were getting their money's worth too, so I didn't feel too bad about it. I wasn't like, oh my God, I'm an impostor I don't really speak Japanese (laughs). That kind of thing.

Once in a while the department, even now gets a call, they're looking for, and the people, they're like folks over at RPI or whatever, they're always looking for interpreters. They're never looking for translators. And often its legal or court proceedings or some management muckity muck is coming into town and they need someone to help in a meeting, and I just think, no I'm not going there. You know? I would mess that up. If it were a hundred year old Meiji Japanese maybe, but I don't know that stuff, right? So I just kind of pass it on.

Q. So from when you started learning Japanese to when you got your first job, it had been six years?

Yeah.

Q. Was that off and on studying or was it hardcore, everyday studying?

Well my first year I was a high school exchange student, so I lived with a host family in Kyushu, and I attended a regular school, and I went with no Japanese whatsoever. So that was a really inefficient but intense learning experience. And then I returned to the United States and studied Japanese at college for two years and then I went back to Japan for my junior year abroad, again another study abroad program living with a host family. That one was a little more like the UAlbany program, so I was attending language classes but then English language classes on Japan at the same time. So it was less intense than my high school experience.

Then I came back to the United States and there was really nothing, there was no Japanese left for me to do in my last semester. I graduated mid-year in January because I'd brought in some credits when I first went into college, so I wasn't doing Japanese that senior year in any serious way. I was tutoring some undergrads, but that was about it. And that was a year that I studied Mandarin. Then the year after I graduated I went to China for a year and I was teaching English and studying Mandarin, but my roommate was Japanese and she doesn't speak any English, and she had no interest in learning English. So actually I got to use a lot of Japanese that year that I was in China, so I sort of still consider that a year of study.

Then I came back to the States, I've lost track of how many years I've covered now, and I spent a year in graduate school in Ohio State in Japanese Languages and Literatures. It was the summer after that year that I had the job at the car parts factory. So, what is that, six or seven years.

Q. Our readers really want to know what level of the Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) you need to be able to pass before you start being a translator.

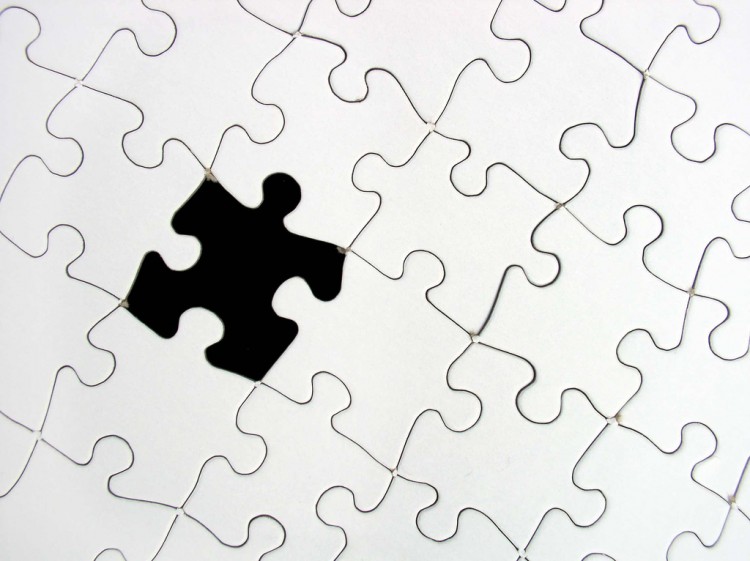

You know the JLPT is one piece of the bigger puzzle. So just because you pass JLPT 1 does not mean that you'll be a good translator and just because you failed JLPT 1 doesn't mean that you can't be a good translator. Because translating is deliberative. JLPT is timed and restrictive – you can't use a dictionary, you just have to read and spit, or listen and spit, right?

The skills the JLPT tests are really not the same skills as translating, so I could give some kid in EAJ202 (Intermediate Japanese) who's motivated, a bunch of dictionaries and a page of Japanese, and I could expect that person to produce something. It might even be something really good as long as they're not too stuck on a particular grammar point, and it's not in classical Japanese or anything like that. If I give them as much time as they need, and all the reference works, that's a really, really different mental process.

You know if you walk into a situation where you're trying to sell yourself as a translator and you say, well I passed the JLPT 1, people are just going to look at you like "so what", I think. They're going to ask you to produce an example of your work. That's really sort of the first key thing.

I had a student who, two years before he graduated, somebody asked me, a friend of a friend, asked me if I could help with a translation, Japanese to English, and I thought, you know, I don't want to work for the friend of a friend – it was actually the boyfriend of a friend. Like that could be good or it could be really bad. And so I said, how about I just give this to an advanced student, what do you think? He said I don't care, he was not ready to pay the professional going rate, which is like $30/hr, it's just ridiculous how much the super professionals do for technical translating. So there's sort of this sub-world where if you're not super professional but you're good enough and you charge less, then you know, maybe you can get that job.

So anyway I knew this student was looking for translation work and he didn't need anything full time, so I asked him if he was willing to give it a shot, and he said well yeah, sure what the heck, right? And he just knuckled down and actually ended up working with one other student because it was a rush job, but they got it done and the guy was happy. It wasn't perfect, but it was what he needed. They were actually translating a patent, again law stuff, God I hate that, so boring. So they translated the document. He was happy and the student was happy and the student emails me and says, "Uh how much am I supposed to charge this guy, I've never done this before" (laughs). And I said oo, well uh… (laughs).

Anyway how did I get there, where was I going with that? Oh! Right, what are your skills. So this student at the time was, he had tried to take the JLPT, just 2, and just barely didn't pass. But does that mean that he couldn't do that job? Absolutely not. He had the document, he had dictionaries, he had the research skills that he needed because he'd taken 205 (Japanese Research and Bibliographic Methods) and he just, you know, he did it. I think those skills have continued on for him in, at masters program too, but going back to that webpage I was mentioning earlier you know, So You Want To Be a Translator, I think that woman also mentions that just having a language skill – it's part of what you need but it's not the answer.

So I would hesitate to tell anybody that, oh you have to do JLPT 1 or something because I worry that people are going to bust their butt to pass JLPT 1 and then they're going to discover that there's no golden path down to Emerald City. And they'll feel very betrayed and angry and unhappy.

Q. So if people say, but no, there's gotta be something you have to pass, there really isn't anything?

That's right, I mean it's really establishing a good reputation, doing good work, doing it in a timely fashion. Um.. what else..

So starting off as a freelancer so that you have something to build up a resume with –

Exactly. You can say, here is an example of the work that I did for, you know, building a portfolio for this company or for that company. You might say how long it took you to turn it around. You want to think about how much you're going to charge as a freelancer. Those rates change over time because of inflation. You don't want to undercut the whole market and then try and raise your prices because people will freak out about it, and you'll kind of get a bad reputation. But like I was saying earlier, you kind of want to charge what you think is the right value for what you're producing. So if you don't have confidence about your Japanese then don't feel bad about having a lower price (laughs).

One of the other things is that translators have to be good communicators not just in the process of translating but also in working with the clients because clients often will come to you – they're blind, right? – they have this document that they can't read, it just looks like chicken scratches to them, but they think the document's important. And you'd be surprised how often it isn't. When you're doing a freelance job you're usually charging by the word, that's usually how they do it, 10 cents, 15 cents, 20 cents a word, something like that, right? Which I like because it means there's no time pressure, you're not charging by the hour, it's not like a lawyer. But in any event, if you discovered that the document is not what the client thinks it is, and you go back to them and say, you know I don't think you want to pay me for this, then that puts you in a really good place. Okay, maybe you lost that job, but they're really happy that you were honest about it. Because the other option is that you translate the whole thing, and then you charge them out the wazoo for it, and it's a piece of crap for them. They're never going to come back to you because they'll think, ah we wasted so much money.

I've had that happen twice. I was asked to transcribe – well, I was sent an audio recording of a meeting. It was a meeting that had taken place, I think in Detroit, and most of the meeting was in English, because it was between two Americans and two Japanese. But in the course of the meeting the two Japanese guys occasionally said something to each other in Japanese and the American's were like, convinced that they were sharing like industry secrets or something like that. So they wanted a translation of what these guys said so they sent me the audio tape and the first fifteen minutes of the meeting there's no Japanese at all, and I'm sitting there listening, like when's it going to show up, what's going to happen? And then when they did start speaking a little bit of Japanese, it had absolutely nothing to do with the content of the meeting. It was stuff like, I wonder when lunch is going to be, or I need to use the bathroom where do you think it is? You know, stuff like that. And so as soon as I realized that I contacted the translation agency and I said, we can't charge these people for this. I'll be perfectly honest, I'll tell you, I'll summarize what it is, I'll sign off on it that that's what it is and I'm not trying to cover anything up, but it would just be wrong Because I would have ended up charging like $500 for, "Where's the bathroom?" (laughs) "Are we allowed to smoke in here?"

So I think it's really good reputation builder as a translator to provide that kind of evaluation service – to look at the thing you're asked to translate and verify yeah, it really is worth your money for me to do this. You don't get paid for that but it's easy to do. It's easy to glance at a document and, translating it take a lot of work, but just glancing at a document to say okay I know what it is.

The one exception I suppose was when I was working in the glass industry, industrial glass production, that was also in Michigan, and they would occasionally send me newspaper articles from a trade journal and ask me to translate what was in the articles. And I did that, this is where I learned, for example, what float glass is. I didn't even know what float glass was in English. I'd look at it and think, there are no industry secrets here, just none. Like I don't recognize anything here that looks like it's a gem, but the American's were so concerned that the Japanese glass industry was doing stuff that wasn't coming through the language barrier. So they just wanted to keep their finger on the pulse of what was being published in those Japanese trade journals. I said okay fine, I don't see why you want this translated but it's your money, you know? Whatever, I'll translate it.

Q. Is there anything when you're translating that is particularly difficult or you dislike coming across?

Certainly when you're interpreting you don't have any leisure time to think about what you're going to say. And I was never trained as an interpreter, I always found taking on the voice of the person when I was interpreting really hard, so I'd always end up doing something awkward, like, "He says, yadayadayada" as opposed to just "yadayadayada". But that's interpreting it's not translating.

Um, translating. God, I wish I had been a translator in the age of the internet. So many things… Because if you were caught without your dictionary, there was nothing, you know? There was no internet, there was no wikipedia, there was no google. And you just kinda have to fly by the seat of your pants.

And then dialect can be frustrating.

Q. We did have some people asking how you're supposed to prepare yourself to translate dialect and colloquialisms without going to Japan and living in the areas that use them.

You really can't. If you're translating, you have to learn that dialect or read it a lot and get a feel for it. Nowadays you can google a lot of stuff so it makes it much easier. It used to be you had to buy a specialized dictionary.

Another thing that I ran into in the car parts factory, and I never would have anticipate it, was a generational difference. So the younger managers tended to use gairaigo 外来語 and the older managers would use some sort of, you know, hyōjun 標準 something. So for example, we had the chrome plating, right? Of the rack and pinion steering components. The younger guys called it pureteingu (プレーティング), and the older guys called it mekki 鍍金, which is the Japanese word for chrome plating. So in a way I was kind of learning two different vocabularies within the Japanese realm because there was that generational difference.

The thing is, when you're translating you can't be a word connoisseur, you have to kinda be a word garbage disposal (laughs). You have to take whatever is thrown your way and you can't say, well people don't say that, or whatever. Whatever is there on the page, you're responsible for rendering in the target language, so you can't get indignant about it. You can get frustrated (laughs), but you can't get indignant about it.

It's a lot easier now I think, because media has made language so much more standardized. Television and the radio and the internet. So if you're dealing with someone from, you know, your generation from Hokkaido, you're probably not going to run into big language differences compared to somebody from Kyushu. You're all going to have the same slang because you're all in the same generation and you're all looking at the same media. And when those older generations die out, then those old differences I think will lessen to some extent.

So I guess the good news is, it's getting easier. It's not impossible to do those things without the internet but it's just much more time consuming. I think translation has become a much faster industry now, because we can find the answers to things so much more quickly.

Q. One person said that they don't know whether to translate literal meanings or cultural equivalencies and what situations would be better for one over the other.

I would tend to agree with translating the cultural thing and not literal. Literal sounds bad and awkward, so to me the best translation is something that does not read like a translation, and if you're just doing literal stuff, you can't get there. This is one of the reason's that I love McClellen's translation of Kokoro, because it really reads as if the novel were written in English in the first place. And a good example kind of a cousin of that, if you will, is Memoirs of a Geisha. Have you read it? I tried to read it, I couldn't get past page three (laughs), but I guess the reason I didn't want to go past page three was because as I was reading it, you know, ostensibly it's supposed to be translation, but as you're reading you know it isn't. It's just, there's so many places that are not a translation.

That's neither here nor there, but anyway you want to represent the culture but you don't want to get too slangy, or too specific to your own generation. So if I am reading along in a translation and I see a expression like "It's the bee's knees" I think to myself, well you know my grandparents might have said that, but nobody said that anymore (laughs). There was probably a better choice than doing that.

Now technical translation, yeah, absolutely just be technical. But literary translation, it's a whole other situation. Somebody's not paying you just to get the meanings of the words, someone's paying you to transform a work of art. So what you produce should be artful, it shouldn't be clunky.

There is an article I wrote, originally for the journal that the BCLT produces, about the challenge of translating catholicism and catholic terms in that translation that I did in 2009. So you've got somebody who is a scholar of Buddhism, but it's somebody who was very well versed and familiar with the catholic tradition, but he had to convey specific ideas to his Japanese audience, and so he had to decide what words he was going to use. And then when I was translating it back into English I had to decide how specific I wanted to be or how general, because he's never super specific. There's this huge vocabulary associated with catholicism, and I wasn't raised in a catholic tradition, so this was a big learning experience for me. Thank God there's a catholic dictionary, and thank goodness Professor DeBlasi, who was raised in the catholic tradition, has his office right next to mine so I was constantly asking him for answers.

So when Anesaki was trying to convey these ideas in Japanese, he would do so but not with these really specific terms that got only used in catholicism. It seemed wrong to me to use those specific terms when I was translating in English, back into English. But you know I had to put some thought into it, so you can look at that article and you'll see specific examples of choices I had to make. What do you call the Virgin Mary, how do you translate that? That kind of thing.

Q. How long did that whole book project take?

A book like that takes me about four years. I don't remember exactly when I started Hanatsumi Nikki, but Teiunshū, which is the one I just finished, I know I started that in the summer of 2010. To be honest, it was largely done by the summer of 2013, but then it had to go through the copy editor and then back to me for changes, and we've been piddling around on this thing since last October. But just today I got the postcard in the mail that I'm going to scan and send a digital copy of to my editor in Fukuoka and that's going to be the cover of the book, so that's the last step. He said as soon as you get that to me, we should be able to get it up on amazon.

Ooh, exciting!

Yeah, it's like, I came home today and I looked at the mail and I was like, yes! It's here, I gotta scan it!

So it took… yeah, but you've got to remember, I've got a day job, right? So the really active time that I spend working on the project most certainly was not three or four years. Really active time, I would say a year, and actually, I asked Jay about this, Jay Rubin, how long does it take you to do a Murakami Haruki novel, now that he's retired and had no other day job to do, and he said it's about a year.

Wow, they're so long though!

I know! But if you're not doing anything else, you know.

Yeah, I guess so, but doesn't he want to sit around and smell flowers or something? Like enjoy his nice leisure time now that he's retired?

Well, you know translating for me, and I think a lot of people, is the kind of mental activity where you have to get into a zone. You can't just pick it up for ten minutes and then walk away. It's not like answering your email, something you can do while you're standing at the airport gate, or whatever. So for me the summer is the best time to get that work done, cause I'm not teaching.

Q. So if someone had a really hard time concentrating and prefers to be doing twenty different things at once, this probably wouldn't be the best thing for them?

Right. Technical translating, not so bad, cause who cares if you have a consistent voice or anything like that, right? But especially a sustained piece of fiction, or a sustained narrative, there's all kinds of stuff, not just the voice that you have to keep in your head, so details that were six chapters earlier, specific terms that might get used, or whatever. You have to keep all that in your head so that you're consistent later on. Cause as a translator you're constantly making decisions, how am I going to translate this particular word? And then once you decide it, it's a little bit like that lecture I did in 205 when I was talking about style, and I said you know, you can choose whatever style you want, but once you choose it, you have to stick with it. You have to be consistent, you can't change midstream. That's a lot of what translating is like, and I know from personal experience, I'll work really intensely on something over the summer and then I'll have to set it aside for a couple months and getting back into it is really hard. Then I'll discover, as I have in the past few months doing fine copy editing and things like that, that there are places where I was not consistent. Thank goodness for search and replace, because then you can go back and fix stuff. But only when I'm reading it in one sitting do I catch those inconsistencies, and I don't sit down and reread the whole thing every time I want to work on it. It's only when I'm doing the copy editing that that happened.

Q. Do you have any fun stories about when you were translating and you made a mistake or something like that?

Let's see, when I was doing Hanatsumi Nikki, it was right at the very beginning, in the opening pages. He's in Switzerland, and this was before I'd done a lot of research on him, I hadn't been looking of photographs of him or anything like that. He's in a carriage, this is like 1908, there's no automobiles, there's horse carriages. He's in a horse carriage in Switzerland and he's going through the Gotthard Pass and they hit a rock or something and the carriage topples over and he falls into the snow, and he laughs about it. He says, oh I had all this snow on my hige, and I translated hige as beard.

It wasn't until much later, I was looking at photographs of him and then looking back at my translation and I realized he never had a beard, he only had a mustache. Ever. In his life. Of course, hige can mean mustache also, right? So I wasn't really sure (laughs) but then I fixed it and I thought, well I'm glad I caught that, cause somebody else would say, what? Beard?!

Okay, two more stories. When I started that project I had read Hanatsumi Nikki in order to do part of my second book, and that's how it got on my radar in the first place. I was really just not familiar at all with Anesaki's work, but I put it on the back burner and thought I gotta come back to that, so then I come back to it and if you look at the kanji that he uses to write his name (姉崎), it could be Anezaki or it could be Anesaki. So it's a difference between a Z or and S, and I just thought Z sounded a little more like what it would be, and I hadn't done due diligence to make sure that was right. So it's still the beginning stages of this research project and I can't remember if I posted it to H-Japan, somehow I got involved in a listserv discussion and his name had come up.

Eventually, I got an email from somebody who provided some answers and then said, oh by the way the name it's not spelled with a Z, it's definitely spelled with an S. I thought, oh how do you know? And then the next sentence said, "I know this because he was my grandfather." And I thought, holy shit! (laughs). So then I felt like this punk, this irreverent punk, you know? I wrote this very polite, very nice email, and actually I still correspond with that grandson, and another grandson, I met another grandson in Japan. There's more than that in that generation, but those two are both former professors, retired professors and have shared a lot of family knowledge with me about Anesaki, which has been great, but I was just so surprised when I got this email, like oh yeah he was my grandfather. Wow okay, you're absolutely right, I'm not going to argue with you about that one. So that was that.

What was the third story… oh, this is an example, it kinda goes back to what I was saying where you catch things only if you're looking at the full project. This happened two weeks ago. The very last changes I made to the manuscript before I said to the editor, please, please just publish the damn thing cause I could keep changing it for the rest of my life.

In the original, he visits all kinds of churches in Europe and when he's describing the architecture, he uses the word tō 塔, the one that gets used for stupa, like in a Buddhist temple. So he uses that kanji 塔 for everything in the architecture, the physical architecture of buildings and I never thought about it until I was rereading it for the umpteenth time that a tō on a church could be a steeple, but it could also be a tower, like York Minster. One of the reasons I went to England last summer was because I wanted to see in person a lot of these places that he had visited in England. So York Minster, for example, does not have steeples, it has two towers. So first of all, we've got that problem of steeple versus tower, and the other problem is tō, as I was saying earlier, you know it's not singular or plural, it just is.

I suddenly realized that I had translated tō as steeple for a building that didn't have one, it only had a tower The only reason it all came together for me is because we had finally finished the layout and we had put the photographs where they belonged in the manuscript, and there's the photograph of the church building and it's clear there's no steeple. So in that context, it looks like I'm an idiot because I've translated it as steeple. I had to do a search and replace and make sure that every building that where I had said steeple, there really was one, thank God for the internet again because I could go and I could find photographs of these building and also make sure that singulars and plurals were correct. Sometimes there's one tower, sometimes there's two towers.

So now that's all been cleaned up, but that goes to that point that when you're translating, you have to do a lot of research. Because authors, they kind of assume that you know what you're doing and they also, they're not responsible for the problems of your target language – like it requires singulars or plurals, and they're not responsible for those cultural differences, like the difference between a steeple and a tower, right? But in English, if you don't fix that, if you don't specify, it's just wrong. So you have to provide – to answer to that other question – you do have to provide that cultural stuff. You know, what if I just called a tō a tower every single time? That's going to be an awful translation and it's going to be inaccurate.

Especially if you have a picture reference right there for them to see.

Yeah, so there was another case in a scene where Anesaki says that a priest is wearing the hat of a priest, and my editor, who was very persnickety, said oh well it should be called a miter, cause that's the hat that priest's wear. And I got back to her and I said that's a good point, but you know what there's more than one priest's hat in catholicism, it could be a miter, it could be this other thing, we don't know, we're just going to have to leave it as a priest's hat (laughs). So you've got to do tons of research.

I'm reminded of a conversation I had with a former classmate of mine in graduate school, he's now a professor at Binghamton, David Stahl. When he was a graduate student at Yale, he helped out a friend, a Japanese friend of his, who had gotten a contract to translate from English to Japanese a Stephen King novel. Now, I'm not a huge Stephen King fan, I don't read Stephen King, I don't know if you do, but apparently these novels are just chock full of all kinds of cultural references. This poor person in Japan was struggling, and so she would do a basic translation and then she'd send Dave all these questions, what does King mean about this, what does this mean in English, what are all these things? And Dave said half the time he didn't know even though he's a native English speaker.

So when you're the translator, the text is unforgiving, you can't fudge it, and literary translation frowns upon footnotes. Now mine have footnotes because it's an annotated translation, but that's a very small wedge of a bigger world. In most cases translating presses don't want footnotes, so you don't have that as an out, you have to figure out how to do it in the translation itself.

Which can be so hard if something isn't clear.

Yes, exactly.

So you have to think in your head, I have to make this clear, but how can I do that? I can't leave it out either.

Right. You have to say, I have to make it clear and what that requires, more often than you'd like is you and only you are stuck having to make a tough decision. You have to say, okay, I'm just going to pull the trigger on this one, it's singular, or something like that. Or, I'm going to pull the trigger on this one, it's a beard not a mustache, because there's nobody there to answer that question.

I think especially when we come out of being a student, we're so used to saying "I don't know the answer I'll go ask somebody else," and once you get into that world you can't do that anymore. I can't tell you how many times I've sat at my desk and thought, who can I ask- I can't ask anybody (laughs). I just have to make this decision myself.

You know what was really good training for me was being department chair and then later university senate chair because you're in a lot of situations like that where you consult with folks but eventually you are the one that has to make a decision and you just have to be comfortable with doing that. It's not always the right decision, but you know, you do it, and you own it.

Q. Would you say that you enjoy what you do? And what kind of person would you say you need to be to enjoy translating works of literature?

I do enjoy it. It's like a big mystery puzzle. Not all of it is fun, I hate copy editing, I'm so glad it's over now, but the initial process is really cool, it's like writing a book, actually, in that you have this really big project with lots of moving parts and I find putting it all together really satisfying. I like organization, I like being organized, I like organizing stuff, and I love reading a sentence in Japanese and rendering it into English that sounds natural. There's something really organically pleasing about that and the more you do it the more comfortable you become with that process.

I guess the only frustrating thing about it to me is that sometimes people will say, how do you do that?, and I don't know how to teach how to do that. I try, you know, I teach EAJ410 and I teach EAJ411 (Readings in Modern Japanese Literature) and we talk a lot about translating, thats the main focus of those courses, but I still don't feel like I know how to teach somebody how to do it. So I guess that's the hard part for me. I wish I could, because I enjoy it, but I guess not everybody would. Not everybody would find that fun.

I wouldn't be a professor of literature if I didn't enjoy language and the beauty of language, and sometimes I'll read a poem or a passage that I just find really moving and wonderful. So that's the cool stuff, that's the really cool stuff.

So other than just being passionate about literature, it helps if you like organization and those types of things?

Yeah, I mean one of the problems with the younger generation, my kids are such great examples of this, is that they live in a world of thirty seconds. My youngest son has a disgusting addiction to youtube and if he watches too much youtube, he starts to act like youtube. In other words, he can only stay focused for a very short period of time. You know, my generation, the people would complain about the kids watching too much television and having short attention spans, but I think it's sort of accelerated right now, and the process of translating anything, even a short story, it's not a short focus thing. It's a project that requires serious attention and concentration and kind of getting lost in that particular text and I don't think people do that very much anymore. I don't see very many folks in the classroom who love reading, there's a few, but most of them see reading as a chore, and I don't think they get lost in a book the way that I like to do.

My kids, I don't want to trash them too much, but they're not here, they're off at boy scout camp enjoying the rain, and not playing on youtube which is wonderful (laughs). My kids can get lost in a book and it's fascinating because they're very critical of their classmates who don't read and who can't find pleasure in reading. So I'm glad that they've discovered that but I think those concentration skills that you need for translation are closely associated with reading a longer text.

And if someone wants to translate they should probably already be reading that kind of stuff all the time. If you don't like reading, there's no reason to want to be a translator.

Oh, definitely. When I was started working on Anesaki I started reading more history of the early twentieth century and also trying to read fiction from the early twentieth century just to get a feel for how people spoke. One of the things that I didn't do until later, but I did do it was, Anesaki also published in English, so I wanted to read his English writing to get a feel for what that sounded like, although I wasn't absolutely sure that would be right, because of course you would have an editor. So what you see on the page might not exactly be what he would have been writing in the first place, it was his third or fourth language. Turns out his English actually was excellent. I went into the Harvard archives two months ago and found some letters that he had written to a former Harvard professor and the English is almost flawless, it's fascinating.

Q. Last Question! Is there anything that you'd like to say to someone who wants to be where you are today? Or if a student came up to you in school and said, I want to be just like you, help me, what do I do?

Uhm… It's hard because I do have students who come and they want to translate, they want to be in Japanese studies, but their incentives are never the same as mine. In other words, they're not interested in Meiji literature, they're interested in anime and manga and video games, and I'm not really sure what the path is to get into that realm. I think it's tough, I think it's really tough. It's not super easy in Meiji literature either, but I think it's different in anime and manga.

I guess the advice that I have for people who, if they want to go into academia, I usually say, well first of all, be absolutely sure that's what you want to do. Understand what it involves, how much time commitment there is, understand what your life will be like, because you see me in the classroom, but you don't see the other two thirds of my life as a professor so here let me tell you what that's like. And you really have to be the person who loves books and who loves being surrounded by books. You know, sure I watch TV and movies, I'm not some sort of nun or something (laughs), but you do it because you enjoy it, not because somebody gives you those assignments. You also absolutely have to be a self-starter. I think as an undergraduate you become very used to being given assignments, because that's how we structure undergraduate education, but if you move onto graduate school and beyond there, then you absolutely have to be a self-starter. You have to be the kind of person who can set personal deadlines and meet them, because otherwise it's just not going to happen.

I think a lot of people want guidance, there's nothing wrong with wanting guidance, but in the world beyond that undergraduate education it may not be there. You'll get advice, but you're not going to have someone saying you have to do X, Y, and Z.

It's not like becoming a doctor or a lawyer. It's not like there's translation school. It's not medical school, it's not law school, it's not professional guild. There's a couple fringe organizations on those sorts of things but that's it. This is not systematized.

Another thing for people who are interesting in translating is to join organizations like that, especially if they're free, what have you go to lose? If they publish a newsletter, absolutely read those newsletters. If it's literary translation, then the British Centre for Literary Translation's journal, I think would be really helpful because it raises all kinds of interesting issues and problems with literary translation. It's not going to get you a job, but at least it's going to get you familiar with the industry and know what the professionals are talking about. It's a pretty small world, they actually kind of get to know each other.

There's also a few translation prizes. There is one that kind of comes and goes. It's actually sponsored by the Ministry of Education in Japan. They provide a list of works that they would like to see translated and they're always current fiction, and the languages that they're interested having it translated into, and people submit their translations and then there's a small cash award. It's like $2000 or something like that to the winner, and then they list the winners every year and then those works actually get published.

So entering contests like that may also help people get a feel for the process, they're probably not going to win, but at least get a feel for the process and then when the contest is over, they can compare what they produced to whatever the winning translation is and probably have a much better feel for what is considered a high quality translation. They're not usually super widely advertised, the trick is finding them. I bet if you googled "translation prize" and then threw in Japanese, you might find some other stuff.

Even Kurodahan doesn't do it every year, there were a couple years where they didn't do it. What happened with MEXT, with the Ministry of Education, they got some big government grant that paid for the whole thing. I'm not sure how long that grant ran, that's why I said it comes and goes, I'm not sure if it's still active right now. It's usually a short story that you're translating, it's not a novel or anything like that.

The stuff that, for example Kurodahan has, they say all translators are required to translate at least one sample from our trial translation, and then they provide you with a PDF of those. And I'll tell you that Edward chose those things carefully, it's not random stuff, each one, I think there's thirty one pages in that PDF, I don't know how many works there are. Each one presents it's own challenges, so older vocabulary that might be a little trickier to parse, for example, dialect, in some of them. You get a choice, you have various things that you can translate, but they do it so that they can kind of weed out the riffraff, if you will (laughs). I'm lucky I don't have to mess with it because I'm already a known entity with them. I can just call Edward and say, I want to publish this, publish it.

Well I think that's it. Thank you so much for answering all of our questions!

You're welcome! It was fun!

Works by Susanna Fessler:

- Teiunshū – The Continued Journeys of Masaharu Anesaki

- Flowers of Italy: A Japanese intellectual's journey to Europe

- Musashino in Tuscany: Japanese Overseas Travel Literature 1860-1912

- Wandering Heart: The Work and Method of Hayashi Fumiko

Want to know more about translation? Check out our other interviews.

- How to be a Japanese Translator with Jocelyne Allen

- How to be a Japanese Translator with Jonathan Lloyd-Davies