When it comes to Japanese pop culture, I'm like a lot of fans. Despite years of off-and-on attempts at studying, I don't know the language well enough to follow the original versions of manga, anime, or live-action drama and movies. And yet, I know enough about the culture – and sometimes the language – to be annoyed about what translators do to them.

Probably all of you have your own pet peeves. One of mine is when tanuki is translated as "raccoon," an error with a history going back to the nineteenth century. And as someone who watches a lot of dramas about food, I groan at how even some of the most devoted fansubbers can't leave well enough alone, and instead come up with many different ridiculous "translations" of "itadakimasu."

Here on Tofugu, these discussions pop up from time to time. A recent article about a new American production of Doraemon was the occasion for much weeping and rending of garments on our Facebook page. A comment on a recent blog post that compared the anime Yokai Watch and Pokemon bemoaned how boring the English version of Pokemon was, since they'd taken out all the Japanese cultural references. You all know what I'm talking about: it's like a dysfunctional relationship. We're totally dependent on translators but, a lot of the time, we hate them. They're the only reason we have access to the stuff we love and, at the same time, we feel like they are why we can't have nice things.

I've always wanted to ask a translator some questions. If they love the products of Japanese culture enough to make a career of translating them, why do they mess with them so much? On the other hand, I also thought: maybe, if we understood more about the process, we wouldn't be so mad all the time.

Well, I was finally lucky enough to have that conversation!

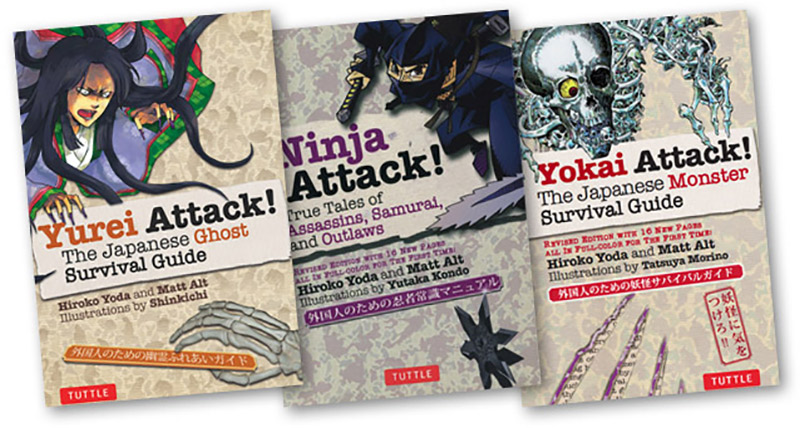

Matt Alt is the co-author of a bunch of cool books about some difficult-to-translate parts of Japanese culture: yokai, yurei, and ninja. I've followed him online for a few years, observing that he knows about everything from 1970s robot toys to Japanese giant salamanders. And at some point I discovered what he does for a living: He co-founded a company, called AltJapan, that specializes in translation and localization. In fact AltJapan is working on the translation of the Doraemon manga right now. I wasn't sure what localization was, but I knew what it sounded like: it's why we can't have nice things, right?

Still, as much as you can tell from just knowing someone on the internet, I felt sure that Matt was a good guy and that his goal would never be to ruin nice Japanese things. He proved both true by being generous enough to answer my questions and – much to my utter shock – managing to convince me for a split second that maybe, just maybe, there was more than ignorance behind calling a tanuki a raccoon.

Q. Localization vs translation in 25 words or less. Go!

Localization is the art — and it is an art — of adapting content into different languages and cultures.

Now I'm going to cheat and go way over 25 words. The idea is for content to "feel" the same in the target language as it did in its native language. The reason "localization" is used instead of "translation," incidentally, is because it often involves a lot of work beyond just the translation of text: manipulation of layouts, even the content itself in some cases, all with the aim of reducing the barriers for the target audience. If something's meant as light entertainment in Japan but you need a PhD in East Asian Studies to make heads or tails of the translation, someone messed up.

Q. A good translation isn't always exact, because word for word accuracy might not convey the intended effect. With puns, for example, a translation has to either change the content or lose the wordplay. You have to change something to convey the spirit rather than the letter of the original, right?

When it comes to Japanese-to-English (and English-to-Japanese) translation, you're talking about two languages with absolutely nothing in common linguistically. Japanese grammar is the reverse of English, it doesn't use articles like English does, it has honorifics, and, in casual speech, often omits subjects entirely. All of that has to be accounted for in translation. The longer and more complicated a sentence gets, the more possible ways there are to translate it.

This is why, for example, the translations of Alfred Birnbaum and Jay Rubin feel so different, even when they're working from the exact same Haruki Murakami texts. It isn't because one is wrong and one is right. It's because there's no precise one-to-one correlation between Japanese and English and translating between them means a constant stream of judgment calls.

Getting to your specific question, yes, wordplay and puns can be really challenging to translate, particularly if they're accompanied by specific images. For example, "time flies when you're having fun" is no problem at all to convey in Japanese conceptually, but it isn't a set idiom. So if there's, say, a drawing of a flying clock on the page, readers might not get that joke.

My company is translating the Doraemon manga series right now. There's one (yet to be released) episode with a gadget that transforms homonyms, words that sound the same, into their different forms. When Nobita points it at some clouds (kumo), it transforms them into spiders (also kumo). Puns with images are extremely difficult to deal with in translation. We handled that one by explaining that it was a tool for learning Japanese and keeping the Japanese homonyms in the English text. But that approach might not work in other contexts.

Q. I get that, in some cases, if everything is translated or reproduced precisely, readers/viewers who don't know Japanese culture will be confused. But for those of us who do know the culture, stuff that we love gets lost – and I think we also sometimes feel our intelligence is being insulted. Let's talk about some examples in the upcoming American version of the Doraemon anime that got our readers up in arms. Some of these changes seem necessary and trivial to me: replacing the circle for a grade with F. Others make me want to scream. Are audiences so ignorant that we really need to have chopsticks replaced with forks?

I wasn't involved in the anime and so can't comment about the decisions made there. I can only talk about my experience in general.

But my basic stance is that if you are passionate enough about Japanese culture to want to understand every nuance, you're passionate enough to learn the language and watch or read it in its original form. I wasn't satisfied with the translations of anime and video games I played as a kid, and that spurred me to study the language so I could do a better job myself.

And now that I am doing that job myself, I can see that things aren't nearly as cut and dried as I thought they were when I was a kid. Translators don't work in a vacuum. It's a service business. There's a bigger picture, and translators are only one (important!) part of a larger mix. There are broadcast or publishing regulations, technical issues, cultural issues, demographic considerations, legal and copyright issues, budgets, schedules, and all sorts of things that affect the localization process.

If Hiroko and I are asked to make a change that troubles us, we never hesitate to raise the issue with the higher-ups, but there are some cases where we get overruled for whatever reason. Sometimes it's just out of the translators' hands. Rolling with that is part of being a professional.

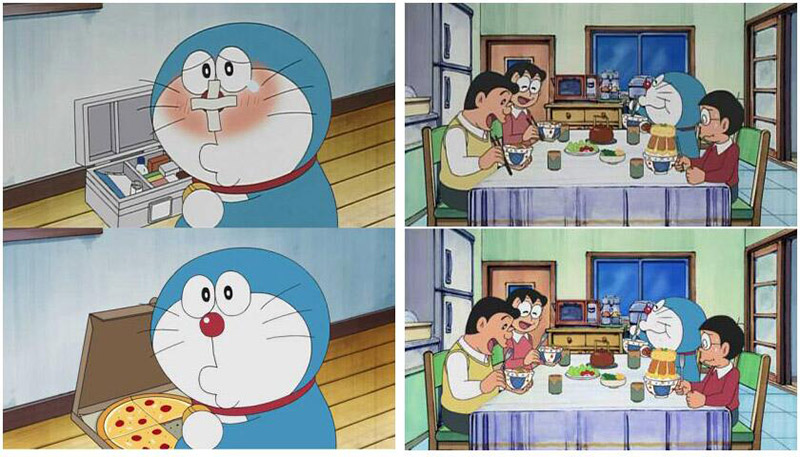

Q. Okay, but if these changes are supposed to make the cartoon more accessible, here's what I don't get: They haven't re-drawn the street scenes, sliding doors, etc – all the evidence suggests that the cartoon is still taking place in Japan. So if they're in Japan, why are they eating American food with American utensils and using American money? Isn't that confusing?

Again, I wasn't directly involved in the anime production, only the manga. But as a localization professional, with any production we're involved with, whether it be a book, a video game, an anime, whatever, we have to clarify who the audience is. Is it for adults? Teenagers? Little kids? If it's for kindergarteners, it's entirely conceivable they've never used chopsticks before, perhaps never even seen them. The people who read this site are deeply interested in Japanese culture, so chopsticks are a no-brainer, but that simply isn't the case for everyone. A lot of people, adults and kids, don't want to learn about Japan. They just want to be entertained. And the Japanese people I know have just as many forks and knives in their kitchens as chopsticks. So it doesn't feel that out of place to me.

Now, I'm not arguing for or against changing chopsticks to forks. I'm just saying that the people who make manga and anime in Japan, in my experience, are open to nearly any changes that might make them popular abroad. We've even had [anime and manga] creators tell us they're okay with changing the genders of protagonists and things like that! That might come as a shock to foreign fans, but it's true. And the bottom line is, when you're talking about a kids' show, how do children feel? Do they enjoy it? That's really what's important in the end.

Q. So part of what you're saying is, sometimes we have to remember that we're fans of a show for five-years-olds.

Yes, exactly! And there's nothing wrong with that!

Q. It works the other way round too. There are Japanese fans of Mickey Mouse, after all.

I did a homestay in Japan back in high school, and recall being shocked at seeing high school kids wearing Sesame Street shirts and openly, unironically loving the show. Guys and girls. For them, it was just a way to learn English with a bunch of cute characters and there wasn't any context or stigma of wearing something for pre-schoolers.

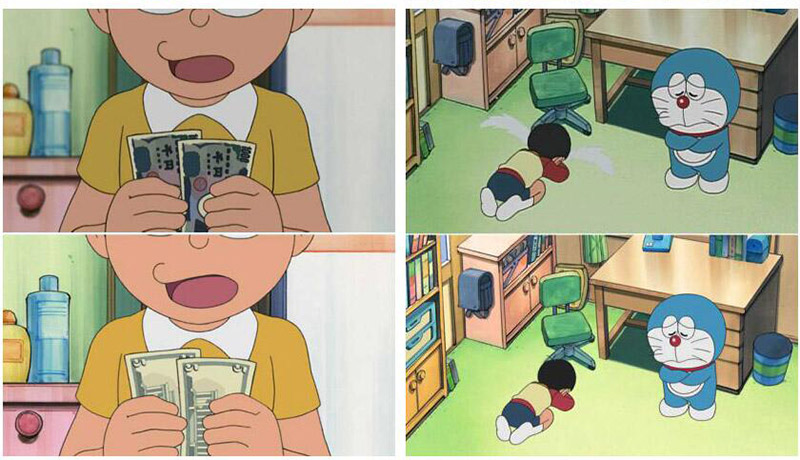

Q. So in that context, some of those changes I was whining about make more sense now. A five-year-old won't recognize that those yen bills are money, so whatever is actually taking place in that scene won't make sense. Whereas if you change them to dollar bills, a five-year-old isn't going to know that they wouldn't be using dollar bills in Japan, so that's not really a problem. And something like what the street scenes look like is a big deal to change but probably not noticeable to a five-year-old. Right?

Speaking from experience on totally different projects, there's a limited amount of time and money that needs to be spent on the most "high value targets," so to speak. When you're adapting something you need to pick your battles. The more changes, the more work, and that means more money.

When you're translating for fun you can obsess endlessly over your translations, but when you're a pro it becomes about delivering quality within the limited amount of time and money you're given.

Q. Moving on from things like eating utensils and money, which exist in all cultures – There are Japanese words/things/whatever that simply don't have English equivalents. Tanuki are not raccoons or even related to them, and yokai are not ghosts/demons/monsters, for example. To me, if Disney needed the animals in the Ghibli film Pom Poko to be familiar to the American audience, they should have redrawn them as raccoons, not just called them by THE WRONG NAME. Aaargh! If American children can watch a movie about Madagascar with lemurs in it, I think a movie about Japan with tanuki in it would not make their heads explode. As far as yokai, we also seem to be able to deal with mythological beings from other cultures like the yeti, so why use a bad translation for Japanese monsters? To me, those substitutions are fundamentally different. Am I just being crazy because I am a geek about certain things?

Believe me, Hiroko and I are huge proponents of calling yokai "yokai" even in English. We made a special point of emphasizing that in our book "Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide." So you won't get any argument from us on that front. In fact, a key part of localization as far as we are concerned is when NOT to localize something. The word "yokai" is one example of that, and we often advise clients to leave it as-is when we're working on their stuff. And even though we weren't involved, I was really happy to see that the Yokai Watch people left yokai in the title.

Now, not having been involved in Pom Poko either, I don't know how it was localized, but that is one helluva Japanese movie. It is packed with cultural references both obvious and subtle, and it would be a challenge even for experienced translators like Hiroko and I to do (a challenge we'd welcome!). My inclination would be to let a tanuki be a tanuki, but that doesn't make the existing localization of Pom Poko "bad." It just means they took a different approach.

For Japanese, tanuki are a very common, everyday sort of animal with a lot of culture and folklore associated with them. You don't need to explain that to Japanese audiences and introducing that concept isn't the point of the film. Calling them raccoons is one way to get that baggage off the table in one fell swoop. Even if, technically speaking, it's wrong, because tanuki are canines while raccoons are in the bear family. But if the creator agrees, the change makes it more enjoyable for the viewers, and particularly if it sells, then there's nothing "wrong" from a localization standpoint. It's just shades of gray. Not everyone who watches that film is going to be as up on Japanese folklore as we are.

Q. I never thought this would happen, but I kind of get it. The way tanuki are drawn must have seemed like a godsend to translators. It is so stylized that they could be raccoons. The traditional incorrect name is "raccoon" and their folkloric personality is similar. Though I now understand, I still hate it.

While I try to recover from the shock of almost seeing that point of view, let's move on to something I have less of a personal stake in. Your company also localizes English stuff for the Japanese market, right? I'm curious about this because I feel like American culture dominates the world so much, what's left about the US that people aren't familiar with? I'm assuming a children's cartoon wouldn't need to substitute chopsticks for forks for a Japanese audience, but I have no idea what you do need to do when going in the other direction. Can you give some examples?

We weren't involved with it, but I heard quite a few changes were made to Grand Theft Auto V, such as editing out the sex scenes.

I can't think of any changes to things we've done off the top of my head. Most recently, we did the Japanese versions of Capcom's Lost Planet 3 and Strider, and helped out on the Japanese subtitles for the film Magic Mike. I can't think of any major cultural changes made to any of those.

But it's a bit of an apples and oranges comparison. Besides the fact that content is for adults, not kids, there is an absolute hunger for translated content in Japan. If something is big abroad, chances are it'll get translated into Japanese. Japan as a nation is very interested in foreign ideas and it isn't at all uncommon to see translated content on bestseller lists.

Meanwhile, with very rare exceptions (such as with manga), there isn't much of a market for books or films to be translated in the US. Americans don't seem to be as interested in what's going on abroad as the citizens of other countries are. It's isn't uncommon for foreign content to get totally remade, such as La Femme Nikita, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, or the Godzilla films. Even foreign material already in English, like the British House of Cards series, gets remade for American audiences. Americans have a much lower threshold for "foreignness" than Japanese do.

Q. Finally – is there an argument to be made that, even if fans think that Pom Poko and Doraemon are ruined by these changes, we should put up with them? Because in the long run, if they are successful, more Japanese stuff will get translated for us, and maybe even more accurately, right?

The key thing to remember is that this is a business, and the point is to sell product – even in Japan, turning a profit trumps everything else. It isn't some freeform artistic exploration for creativity's sake. And when it comes to localization, nobody wants to change anything for the heck of it. That's more work and effort on top of the already huge effort needed to translate it! They do it because they think it will make the end product more popular and thus more profitable. That's the name of the game.

As I said before, I think that if you're passionate enough to get upset about a localization, you're passionate enough to channel that energy into learning the language. And let me be clear: I am not saying anyone is wrong for expressing their dissatisfaction. I'm not in the business of shutting down personal opinions. What I am saying is to seize that discontent. Passion and emotion are powerful things. Use them to better yourself and, maybe, in the future, better the localization industry. Dissatisfaction with the status quo drove me to learn Japanese as a kid, in the late eighties, when it was far harder to do than it is today. And believe me, I'm not the world's greatest student or linguist. If I can do it, any motivated person can.

So consider this a challenge – if you think you can do better, do it! Study hard, pay your dues, and wait for the chance to prove that you can. But along the way, you might find things aren't nearly as black and white as you think.

Check out a few of Matt's awesome books: