When the review copy of Ken Taya’s art book, “Enfu: Cute Grit”, arrived at the Tofugu office, I knew I had something special in my hands. It was one instance where judging a book by its cover was very appropriate. I sat down with headphones full of music and cracked it open. What followed was almost a religious experience.

Seattle-based artist, Ken Taya, aka Enfu, grew up between the U.S. and Japan. From this life experience, he forged an art style that has won him praise as a video game industry professional, as well as laud from art critics and lovers of color the world over.

Tofugu got the opportunity to talk to Ken about his art, career in the video game industry, and what it takes to become a professional in both sectors.

Welcome to Enfu

Q. Tell us a little about Ken Taya.

I’m a Japanese American bilingual nisei 二世 video game artist. I’ve been making video games for over 13 years as an Environment Artist. The types of games I’ve worked on range from Halo 3 to Scribblnauts Unlimited.

I went to University of Washington and Digipen Institute of Technology. I love hip hop, reggae, and old school rap. I used to breakdance in high school, but if I tried that now I’d snap my neck.

Q. What about your artist name Enfu? What does it mean and why did you choose it?

I’ve always liked monkeys, and my nickname in high school was “flying monkey” because of the way I played basketball. Enfu is the on’yomi (Chinese reading) of the Japanese Kanji sarukaze 猿風, which literally translates to “monkey wind”. I rarely go by the kanji, but that is the background.

Q. When did you first start drawing?

All kids draw, so I was just like any kid and have drawn since then. I guess drawing was always fun for me. What’s hardest is to stay childlike.

Q. What do you do to stay childlike?

This is a scenario that illustrates a time I realized I lost my inner child. I was watching my daughter (then about 4) play Scribblenauts on the Nintendo DS. She was wide eyed playing this game. All she knew was she could write anything and it would appear in the game. She didn’t even know how to write yet.

What I’m trying to drive home is she didn’t yet know how to use the tools, but she was excited about spawning the next object. After many sessions of coaching her on how to spell the names of kitchen and tea items, she eventually got around to asking me “Papa, can I make an ocean?”

I outright told her “I don’t think you can make an ocean in this game, honey.” My reply meant nothing and she asked me how to spell it anyway. I reluctantly spelled out ocean and, to both our surprises, an ocean popped up!

At that moment I realized the adult me was beaten by a child. I was saddened by the restraints I put on myself as to what could and could not be done. I mourn the loss of the child in me, and it will be a lifelong struggle to regain that childlike perspective. As of now I only can harness the inner child in spurts. It is usually the time when I convince myself ‘I can do anything!’

Art and Video Games: A Regular 9 to 5

Q. When did you know you wanted to pursue graphic arts as a career?

Well it was more the video game industry I wanted to enter. After graduating and working as a freight forwarder, I decided I wanted to be a part of making something cool. That’s all I knew. I just wanted to ‘make something cool’.

So I reassessed what I enjoyed, which was drawing, speaking Japanese, and playing video games. Then I just said to myself, “What kind of company allows me to do those 3 things specifically and (hopefully) locally as well?” It was Nintendo.

I looked up “how to get into Nintendo”, and Digipen came up as the school next to Nintendo. I took the test, got in, and that’s how I started my journey.

Q. How did you get started as a professional artist?

Well, I don’t really know if I’d consider myself a ‘pro’ yet. But in terms of earning a salary making art…pretty much right after Digipen.

Digipen did a great job putting me in probably one of the most stressful, competitive, supportive classes of students. I’m still friends with those guys to this day, and I have fond memories of us all grinding away on our projects and teaching each other.

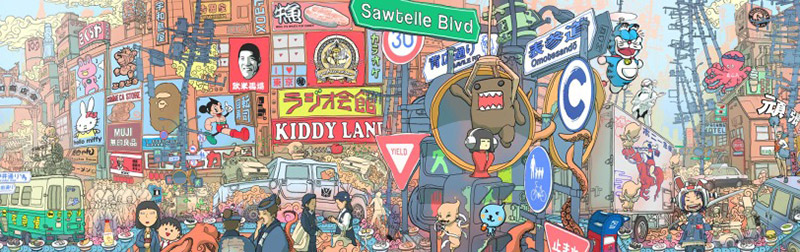

I started Enfu in 2005 as a creative side outlet because I wanted to make my own thing, not just what I’m hired to make for a company. I started off making screenprints, and my first print, Tako Truck, embodied the content that meant something to me: East meets West…we’re really different yet really similar.

Q. So, after Digipen you got straight into game design?

Well, most of my formal titles were in the realm of Environment Artist, which is only a small slice of the production pipeline in game creation. I would model the digital 3D terrain/buildings/props that are in each scene. Only recently, when I started to make my own games/apps, have I really taken on the role of Designer. Everyone has a ‘designer brain’, but many don’t pursue it and stay within their discipline.

Q. What does the Environment Artist do beginning to end? Are there specific steps to the creation process or is it more more loose? How long does the whole process take on a game the size of Halo 3?

Well, it’s hard to summarize, as it is a really complex process. You basically need to translate what the Designer needs for gameplay and combine that with how the Concept Artist interprets that same scene.

Then, aside from the complexity of creating the 3D models, texturing them, creating shaders for each texture, and flagging surfaces to react to effects a certain way, you have to budget the amount objects that can exist in certain areas whilst keeping the game performant.

Next, you have to make sure all your textures fit within the budget of the level, create geometry like grass and decals like signage, create convincing lighting scenarios, check all your portals dividing the level for loading purposes, and so, so much more technical considerations to weigh. Do players get caught up in the geometry? Can other players identify other characters in front of the busy background?

To me, it is much much more complicated than drawing a picture. Also, much of environment work is a collaborative process, so managing and communication makes this discipline very interdependent.

Q. For our readers who want to know more about the video game industry as a whole, what does the whole process of game creation entail, beginning to end?

I’ve yet to complete a full game by myself, I’m still on that journey with my iOS match game. But, in a nutshell, a game is born first with a core game mechanic, then the look is conceived. After that, a whole body of work is required to execute the game (asset creation, optimization, level design, UI, animation, testing). Finally, scratch that a couple times and repeat the process until you finally end up with a game. I’ve been fortunate enough to have worked in many of the roles on the art side from beginning to end, aside from the music and programming disciplines. A game has to be fun more than anything else. Looking good is often simply a secondary priority. Many, many artists often forget that.

Q. What advice do you have for our readers who may want to get a career started in the video game industry?

You have to prepare yourself to play games, not as a consumer, but as a developer. That means, first play for reference but allocate most of your time to improving on your actual craft.

But if you’re considering going into the industry…you’ve probably already played many games throughout your youth. I would encourage you to drop everything and draw every single day (assuming your discipline in game design would be art). Then learn the basic digital 2d software like Photoshop. You’ll learn the rest in school. Explore a lot of analogue disciplines before fully pursuing digital tools. Its kind of like the advice of learning on an acoustic guitar before you play electric. You learn to be precise with your fingers on the fret board before you get away with sloppy techniques on electric.

Q. It sounds like the best way to enter the field is with formal training. Is it possible to enter into a video game arts career without going to a school like Digipen?

Of course. Anything is possible. Of course I’m biased toward Digipen because that is where I went. I know a lot of other successful artists in the game industry that aren’t from Digipen. But I believe Digipen provides more training that goes beyond just the traditional/technical skills of rendering art. They also teach you to collaborate with their Programming department (which produces top talent) and the ability to collaborate with Programmers and other departments is an art in itself. It’s one thing to be able to draw, it’s another thing to be able to make a game. Pick any school if you want to draw. If you want to make games, pick a game school.

Q. What advice do you have for readers who may not want to make art for video games, but just make art, like you do with Enfu?

Draw everyday. Draw something that means something to you. Then try to sell it even though you’re not ready. It will toughen you up. Nothing forces you to consider your personal convictions better than having to literally stand behind your work at a table. You will hear many art theories by people who practice a lot, but if you don’t put it out there in action, you really won’t know.

Enfu Art is Born

Q. When did you start your Enfu side projects and why?

I was working on F.E.A.R. at the time, and I really curious to see what else I could make other than suspense horror type FPS.

Q. Do you consider your Enfu work as more important than your video game work? Would you ever give up one for the other?

I’ve described it before in this way: Working on console games millions of people enjoy, working on Enfu thousands of people enjoy, and drawing a picture for my daughter making only her enjoy…they are all equally rewarding.

Q. When did you first feel like you had “your style”? In your book, there are examples of figure drawing and realistic styles. You have the skill draw in any style, so what is it about the iconic, shiny, and colorful that you feel represents you?

Well, I had put a lot of thought into it before I started doing the screen prints. I wanted to create something that looked hand drawn (hence wavy lines), but also reflected content that was relevant to my background. I don’t just find a perfectly rendered image of a tree, it needs to be more than that. The style keeps getting refined and changing. But the gist of the style is well explained in my book. Line heavy, colorful, and busy. It really has its roots in what influenced me growing up. Japanese manga, games, and anime. Generally line heavy, colorful, and busy, but also weighs more in favor of content that is whimsical than mature, cute more than gritty.

Q. Let’s talk “Enfu: Cute Grit”. Your book is wonderfully massive. How did such a gigantic project come about?

Well it took around 2 years to make the book which contains 10 years of my work. My publisher Chin Music Press worked closely with me to compile the gigabytes of data I sent their way. I trusted their book designer, Dan D Shafer, to design the flow and look of the book. He just killed it.

Q. I love the way you use small icons to create patterns. What inspired this idea in your work?

I can point to the exact moment where this movement happened for me. I was working on marketing materials for Scribblenauts Unlimited, which was a launch title for the Wii U. I wanted to make an epic gif using all the 3-frame emotes used in the game. As I was putting it together, a coworker came by showed me a better way to put it together. He made it for me programmatically way quicker than had I done it manually. That was the “aha moment”. I asked him to create for me a basic pattern tool, which he did. I did some demos of this pattern tool when I was on book signings and there was feedback that people wanted to buy it. I am currently working with a partner to bring this proprietary software to market.

What I learned from my years as an environment artist is that a big scene is the sum of many many many small parts. And the engineering and creation of these products have so many technical requirements to meet, whilst having to look and feel good on a macro level. But this all starts with thousands of “lego parts”. In a game like Scribblenauts Unlimited, there are literally thousands of things you can spawn. You type in something, it pops up. The experience working on a game like that really only emboldened me to build a huge asset library of little images, and then figure out what to make out of it all. There are so many things you can make if you design your building blocks to be replicated quickly, and engineer the machine and process in which products are made.

Q. You have an Enfu app out for iPhone and iPad that lets you use your iconic art as emoji. So it seems only appropriate that I ask you a question with your own art and you do the same with the response. Here goes:

Translation: How long does it take to draw one picture icon?

Translation: First I don’t have any good ideas. I try drawing something, fail, and scrap it.

Then I have a better idea and draw it. It is good and it’s party time!

Takes around 30 minutes. I repeat this over and over just chasing that carrot.

Q. You’ve said that your daughter is your muse and inspired your character, Elly. Does the musing come through things she says or is it more unspoken?

Well the whole book Enfu: Cute Grit covers kind of covers the transition of my content being mostly about my Asian American identity, into capturing the fleeting innocent imagination of childhood. I think every parent sees their child and becomes appalled we were once that age, and covets the child’s perspective.

Q. What’s the story behind your art on clothing? How did that come about? Is there anything special about using clothes as a canvas?

Curiosity led me there. I wanted to see what I’d learn from creating a different product offering. That is generally why I like to make many different things. I like wearing trucker caps, so I wanted to make my own. It’s cool to see people wearing them in public.

I was exploring surface design, which is a discipline already similar to what video game environment artists already do, texturing surfaces. I learned more about it, thought about other applications, and clothing was one of them. I invested much of my effort, and I am continuing to invest in this now, into making a pattern-making software that fits my needs.

Q. What artists have had the most influence on your work?

326, Kozyndan, Toriyama Akira, Taiyo Matsumoto, Mr., and Takashi Murakami. Basically many line heavy, intricately busy, youthful/childlike , and colorful Japanese style renderings are really interesting to me.

Japanamericana: Creating Art That Straddles Two Worlds

Q. You lived in Sendai, Japan for a time. When was it and why did you move there?

My dad’s work brought us to Sendai as he is a University Professor. He taught at Tohoku University while I endured middle school with my broken elementary Japanese skills. (Still elementary by the way.)

Q. How did your time in Japan influence your work?

I was struggling in all my regular Japanese classes and my teacher, Miura-sensei, influenced my psyche by encouraging me in art class. He really made it a point to empower me to pursue art. Maybe because I was having fun, compared to my other classes, this let me know there was a sanctuary in art. I was in 7th grade at the time and it was impactful. I wouldn’t understand it all until much much later. I really wish I could thank Miura-sensei for his positive impact on my life.

Q. Your work has been called “a celebration of how cultures are enlivened by their commingling.” What, in your view, are ways that cultures can commingle to their betterment?

Well, the U.S. is kind of like that. We try to adopt other cultures’ ideals, fold them into our own, and then own them. The issue is more we don’t often commingle. We usually pick out characteristics that make people different and exaggerate them, without picking those exact same characteristics and trying to bridge the gap, while realizing we have an equivalent quirky difference. There is something extremely satisfying about the transformation from stranger to friend.

Q. As an artist who deeply understands the blending of Japanese and American culture, how do you feel Disney handled this task with its film “Big Hero 6”?

Now, I’m going to sound super critical and nitpicky, so let me preface this with the fact that, overall, I loved the movie. But you asked, so here it goes:

I’m usually super vocal about the lack of Asian Americans represented in media. I’m also trained as an Environment Artist, who has himself had experience working on fictional hybrid Asian themed sets. That map (in the link) was the penthouse of a corporation called Sino-Viet, a total hybrid Asia-generic set. I mean, there is a rocket launcher in the river between a stepped zen garden. Who builds that, right? So I totally understand bending the reality for the sake of fulfilling the design needs of the deliverable.

With that said I still had issues with Big Hero 6.

Character:

Finally a half Asian lead!

Hiro as a character displayed absolutely no Asian American/Asian qualities whatsoever. He basically had a ‘white’ personality with an Asian name. What do I mean by “he has no ‘Asian qualities’ “? Well, let’s see, there is already a precedent for other cultures. Hispanic characters throw in Spanish words or slang. African Americans have their own swag carved out. Asian Americans…what defines them as Asian American? It is a mystery, almost. Lilo and Stitch had Hawaiian culture ingrained in its dialogue. Even Po from Kung Fu Panda had more Asian in him than Hiro, and he was a Panda and voiced by Jack Black.

Environment:

Yes, this is a fictional town, I get it. But if you’re going to portmanteau city names, you’re establishing solid reference points. San Fransokyo was just San Francisco “ching-chonged up”. It was supposed to be a mix between SF and Tokyo, but many representative props weren’t “Tokyo” at all. They took the red shinto gates (torii) and put them on the bridge.

They’re gates of shrines, but to me they represent totally different regions of the country. What if a Japanese Anime had a hybrid set based on NYC and put Mt. Rushmore on top one of the buildings? Does sprinkling in Baptist church steeples in the environment make it American? Its like an effort was made to highlight old Japan, not modern Japan, which is kind of sad. Tokyo Tower instead of Sky Tree.

What they got right were the vehicles, especially the police car. A bit of redemption.

Also we need to stop putting chopsticks in hair buns and calling that ‘good enough’. Yeah so, Japanesey pagoda-like roofs curved up corners = not Japanese.

All these little details are petty in the bigger scheme of things, but these petty details are what Environment Artists need to take care of.

Let’s hold San Fransokyo to higher standards. What did Treasure Town in Tekkonkinkreet look like? What about the hybrid fantasy world Sen strolled through in Spirited Away? I believe those environments were twice as lush, more embellished, with way more attention to detail than the cityscape of San Fransokyo.

All that to say some things were a bit “off” to me, but I know it’s passable for most. I know most of my critique can seem a little like “this ramen isn’t as great as the ones in Tokyo”-type comments, but I’m happy that I get to eat good ramen stateside. I’d much rather be slightly misrepresented than have no representation at all.

Q. What is it about Japanese aesthetic that you find most appealing? How do you incorporate this into your work?

Well its not just the Japanese aesthetic, but also the Japanese psyche (content) which speaks to me. Aesthetic is the shallow shellac which identifies or brands the work, but content is what keeps people engaged in your work.

The Japanese aesthetic not only prioritizes the line, being line heavy, but also unabashedly uses color, and, to a lesser extent, plays with the contrast between nothing-ness and busy-ness.

Japanese content mirrors the culture in its idolization of youth, thematically and aesthetically. This appeals both to children or the inner-child. Though cute or “kawaii”, the Japanese psyche promotes grittiness, hunkering down, working hard, and perseverance. These characteristics are necessary to focus on the intense line work.

Wrapping Up

Q. What is the one question you wish people would ask you, but never do? (Then answer it!)

Most people would never really ask this outright because it may sound offensive:

Q. Why are you so obsessed with being Japanese?

My answer would be different depending on who asked it.

American: I’m proud of what makes me different.

Japanese: It’s kind of stupid to be proud of something you had no choice in.

Q. How do you feel about the Seahawks going to the Super Bowl?

Answer:

Get Your Own Cute Grit

Big thanks again to Ken Taya for answering so many of our questions. If you’d like to buy his massive art book “Enfu: Cute Grit”, get it here: