Over all these years reading and writing about Japan I couldn't help but notice a certain name popping up more and more: Brian Ashcraft. Whether it was on Wired, Kotaku, the Japan Times, or his various books, I kept seeing him. Eventually I became a fan of him too. He was (and is) one of the most well read and well written experts of Japanese culture that the internet has to offer.

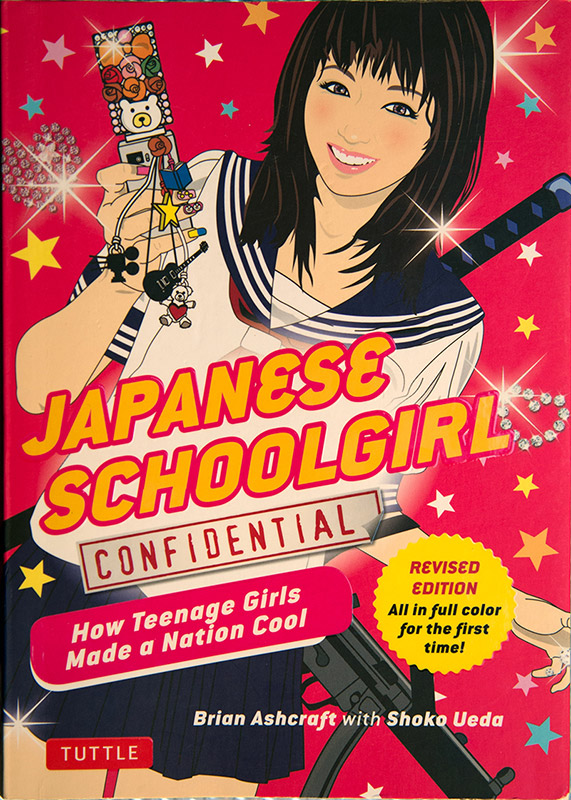

So I was especially pleased when we got a copy of his latest book, which you can read more about in yesterday's review of Schoolgirl Confidential. I wanted to learn more about how he chose the topic of schoolgirls to write a whole book about though, so we asked him to the interview dance and he said yes.

Let's learn what goes on inside the brain of Japan-expert (and schoolgirl expert) Brian Ashcraft.

Name: Brian Ashcraft. Occupation: Author Of Japanese Things

Q. What's your story?

Let's see, where to start. I've been in Japan well over a decade now. I ended up coming here on a lark of sorts. I'd always been interested in Japan since I was young, growing up with video games and anime. But it wasn't until I was in college spending my summers at a movie distribution company that I thought Japan might be an interesting place to visit.

The movie distribution company was called Rolling Thunder Pictures and was started by Quentin Tarantino. My boss, Jerry Martinez, visited Japan to try and get the rights to the iconic yakuza film Battles Without Honor and Humanity as well as a Gamera movie. He was unsuccessful, but had a wonderful time in Japan. I thought after graduating, I should visit. I did. And now, here I am married with three children. The plan was only for a few months, but it's obviously turned into a much longer stay. Japan is now my permanent home.

Q. Why schoolgirls?

Ha, why not? There's actually a few good reasons. A friend of mine said he had a friend at Wired Magazine who was looking for Japan-based writers and that I should pitch articles. I did and after writing a bunch for Wired, I ended up as a Contributing Editor for several years. Besides doing a couple features, I wrote about Japanese schoolgirl trends. So for a good chunk of time, I followed their fashions and interests, read their magazines and absorbed their culture. An editor named Andrew Lee who was at Kodansha International was keen to do a schoolgirl book and knew I had written about their trends and that's how this project was born.

But, in a larger sense, I wanted to explore the eternal question as to why schoolgirls continually appear in Japanese popular culture. Why are schoolgirl characters in so much of the visual culture in Japan? Why do they keep popping up in commercials, even if the ads are for things you wouldn't necessarily associate with them, like bread or health insurance? The answer wasn't as straight forward as you'd think, and I thought the book would be an interesting way to look at some larger issues in Japanese society.

Q. Could you give us a synopsis of Schoolgirl Confidential?

Certainly. The book is a look at how schoolgirls, and in turn young women, have influenced and come to define Japanese popular culture. It sets out to answer the question as to why schoolgirls are so popular in Japan.

Q. From the original idea, through the research, writing, and editing up to publication, how long would you say this whole project took?

This was a several-year project that began long before it got the greenlight. As I mentioned, my first paying writing job was covering Japanese teen trends for Wired Magazine over a decade ago. To do so, I had to immerse myself in their culture. So the book really drew upon that backlog. Andrew Lee, who edited and designed the book, was super keen to do a book on schoolgirls. I figured out a structure and a way to cover this topic that worked for me, and then, I believe we went into production for about a year, a year and a half.

Q. How much of the book was you and how much was your wife, Shoko?

I really wanted to do this book with Shoko for a number of reasons. One of which was that often when you see schoolgirls written about in English, they are portrayed in a somewhat abstract and nebulous way. Yet, these young women grow up, get jobs, maybe get married and perhaps have families. So, it was super important that Shoko participated, because I wanted to ground the project in reality. This is also why we spoke with numerous Japanese women of varying ages.

Of course, Shoko was around when I was writing for Wired, so she's been following these recent trends as well–and was an invaluable source of firsthand information when discussing fads of the 1980s and 1990s. Friends and mothers of friends and even grandmothers helped fill in everything from the pre-war years to the 1970s.

Like with any project, collaborators have an huge influence, and Shoko most certainly did.

Q. Reading through the book, it really felt like there was only one voice, so the two of you seem to mesh really well. Was it easy for you to work together?

When my books have a "with" credit that means I wrote it. So, the book I just finished, "Cosplay World" is credited as "By Brian Ashcraft and Luke Plunkett." That's because we literally split the writing 50-50 and then rewrote the heck out of each other's work. It's now hard to tell who wrote what, and that was what we wanted to do. We've been working together for a long, long time at Kotaku, so this arrangement worked best.

For "Schoolgirl Confidential," the book is in English. Shoko will be the first to say she isn't a writer, so for the sake of efficiency, I wrote all the words. That doesn't mean to say her influence isn't felt in those words. They are. Likewise, as with any good editor, Andrew Lee's influence is also felt in the text. If a book is a collaborative process, then it should be a collaborative process. Writing is so lonely! I love working with others, whether that's a great editor or a wonderful collaborator. I was able to funnel all that into a singular voice, which is perhaps why you felt that way.

Q. This book seems like it was extensively researched, how much of the information did you know prior to the decision to publish it, and how much did you learn in your journey to write it?

That's hard to say. Lots of the information was stuff I had picked up over the years writing for Wired. Other stuff was the result of talking to people or reading up. The really interesting stuff for me was learning about the uniforms, because uniforms are often taken for granted. I really wanted to roll up my sleeves and learn as much as possible about that. But I really loved researching and writing all the chapters, whether that was pop music, movies, or games, because this is stuff I am interested in.

Q. How did you go about doing the research part?

One thing that was very important for me was that the book tackle a variety of issues in a way that really hasn't been done before. Sometimes, students email me, saying they've used the book at university for papers and whatnot, and for me, that was the point. I do see this as a serious look at schoolgirl culture that certainly could be used in a course on Japan, but by "serious," I don't mean "dull" or lacking humor or wit. I still wanted the book to be fun, but have a certain gravitas. This is an earnest look at popular culture.

So, to answer your question, the research really started when I was writing for Wired, covering teen trends. For this book, it then became a matter of doing more precise research for each chapter. And then creating a book that, hopefully, even students interested in Japanese popular culture could use.

Q. You spoke to a decent amount of famous (or once famous) people, like Chiaki Kuriyama (Kill Bill, Battle Royale), who was the hardest person to arrange an interview with?

Everyone I spoke with was incredibly generous with their availability. Surprisingly, nobody was difficult at all! Perhaps, I caught them at a good time? I'm not sure. But they were all great.

Q. Do you have any fun stories about any of the interviews?

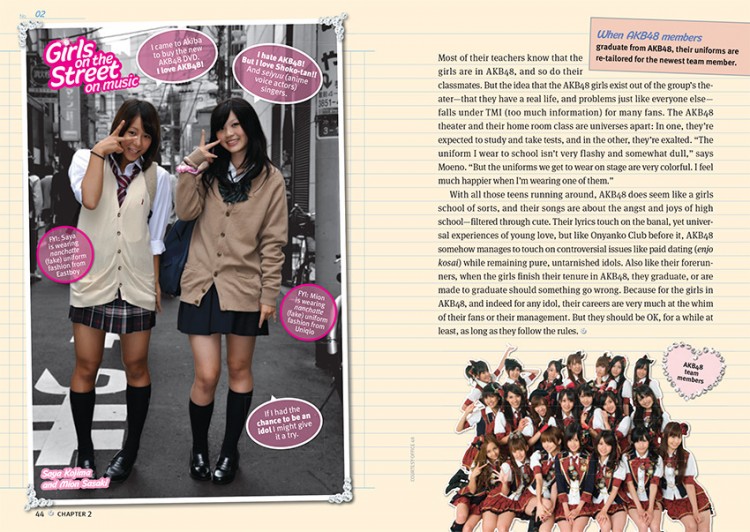

Oh sure. When I spoke with the AKB people about setting up an interview, they asked me how many members I wanted to speak with. I thought about saying all of them, but instead, said if I could speak to three who were still students, that would be great.

After the interview, I remember telling Shoko that Rino Sashihara seemed like she had star quality. So I wasn't really that surprised when she later became one of Japan's most famous idols!

It was also really cool interviewing Scandal. The group is now a major band, but when I interviewed them, they were were largely unknown. It's exciting to see people on their way up.

Q. What was the most surprising thing you learned in your research on schoolgirls?

I think the thing that surprised me the most–or even saddened me somewhat–was that during the war, schoolgirls wore pants so they could run away from U.S. military bombs. I remember talking to my wife's grandmother about that, and it was a detail that really made the horror of the bombing raids much more immediate. These kids were dealing with stuff like this on their way to school.

Q. So schoolgirls are more than just people, they're a symbol to Japan and the world outside it. Without spoiling the, I guess, conclusion of the book, why is the Japanese schoolgirl so pivotal to Japanese society?

Well, in the past, symbols of Japan were either the geisha or the samurai. The schoolgirl, however, encompasses qualities of both, which is why you see schoolgirl characters appearing in a wide range of media–from fighting games and horror movies to coming of age stories and teenage love stories. Schoolgirls can mean and embody so much to such a wide section of Japanese society, from kids to adults as well as to men and women.

Q. In the book you, every once in a while you have these really poignant statements. Like this for example, "Schoolgirls represent the common people, they are the soul of the country and bear the brunt of society, they are the ones who keep it going." (p.145) Could you explain that a bit?

Certainly, in that section I was talking about how schoolgirls are often depicted in art. In the past, French painters might have painted field workers to explore larger issues, but today, many Japanese artists, both male and female, use schoolgirls to explore problems in society, such as suicide or a lack of individualism, or merely, the stresses of modern life and consumer culture.

Q. I know some people find the layout of the book to be a bit of a turnoff, but I feel like it really fit the topic and the discoveries to be made about these young women and the world that's grown up around them. Who's decision was it to make it look so much like a fashion magazine?

Oh, wow? Really? I love the design. Andrew Lee, who edited the book, also did the design. He designed my arcade book Arcade Mania!, too. He's a fantastic designer. The feeling was, look, this is a book about schoolgirls, so let's embrace the visual look of schoolgirl culture. We didn't want to shun that look at all. Why make a book on schoolgirls if you are going to shy away from schoolgirl culture, you know? What's the point?

Q. What is your personal favorite chapter of the book?

That's hard! I mean, I studied art history in college. So, for example, going to Takashi Murakami's studio for an interview was incredible. Ditto for interviewing Makoto Aida, an artist I had studied years ago. But, I spent time in the movie business in Hollywood, so writing about movies was great, too. And I like games, anime, manga, fashion, media, history–you name it. I like 'em all!

Q. Was there anything that didn't make it into the final edition (that you wish had)?

Hrm. Good question. There was one famous fashion model we had talked to about the book, and she seemed interested, but we weren't ever able to finalize an interview with her. She would've been interesting to interview, I think.

Q. What is the one thing about schoolgirls that nearly nobody knows?

Well, I'd say ultimately there isn't. Because really, even if the adults don't know something, the schoolgirls themselves do. That being said, some of the historical issues surrounding things like uniforms, such as where the first sailor style schoolgirl uniform appeared, have been somewhat foggy until recently. Stuff like that, maybe, because a good chunk of schoolgirl history and culture doesn't always make it into the standard history books!

Q. What is one question you hate getting asked (and then can you answer it for us?)

The appeal of schoolgirls is just about sex, right? Um, no. This question actually ends up showing a lot about the person who asks it, revealing what kind of schoolgirl media he or she has seen so far.

Q. What is the one thing you wish we asked you in this interview?

Did you write the book on a computer? Nope! I first write everything out longhand with a 4B pencil, and then I type it up. I love writing with pencils, and of course, with my day job at Kotaku, doing so is simply impossible due to the lightning speed at which the internet moves. Mono 100 are my favorite pencils, but I also like Hi-Uni and the new Blackwing 602s.

Q. Where can people find you? (books, websites, Twitter, etc)

You can find me on Twitter @Brian_Ashcraft or on Kinja should you want to read only my Kotaku posts. Luke Plunkett and I recently published Cosplay World, a book on cosplay that we are both very proud of. Besides the great content, it's a flexicover that was printed in Italy and has a wonderful coffee table book feel to it. Here is my Amazon author page.

Q. What are you working on next?

Right now, I am writing a book on irezumi for Tuttle. I am collaborating with Hori Benny, an Osaka-based tattooist and an all-around good dude. After that, I have another book in the pipeline. Besides that, I write for Kotaku on a daily basis and do a column each month for The Japan Times. I like to keep busy. Life is short. Writing is fun.

Q. Anything else you want to say to the Tofugu reader people?

I love Tofugu! This is a great, great site that does a solid job of covering Japanese culture. I've been reading it for years. The comments section is also fantastic, so keep up the good discussion Tofugu reader people and keep the wonderful articles coming Tofugu writer people!