Movies like Pacific Rim and the thankfully-better-than-last-time American Godzilla have been rekindling a love for giant monsters. Kaijū have been igniting the imaginations of children everywhere since dudes in rubber suits first started wailing on other dudes in rubber suits. It’s easy to get swept up in the delight of these movies and their fantastic creatures, but let’s not neglect the real-life kaijū you might see on a trip to Japan. You might not see Godzilla during your travels, but you could very well bump into one of these ten Japanese beasties.

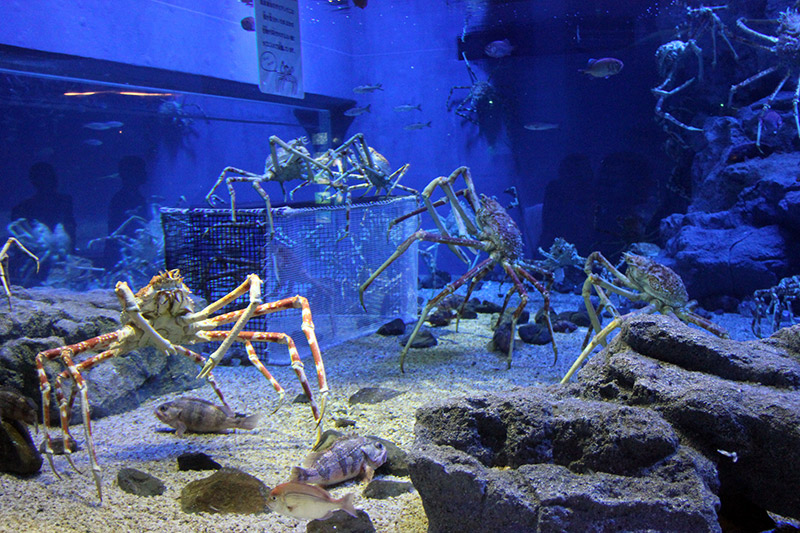

#10: Japanese Spider Crab

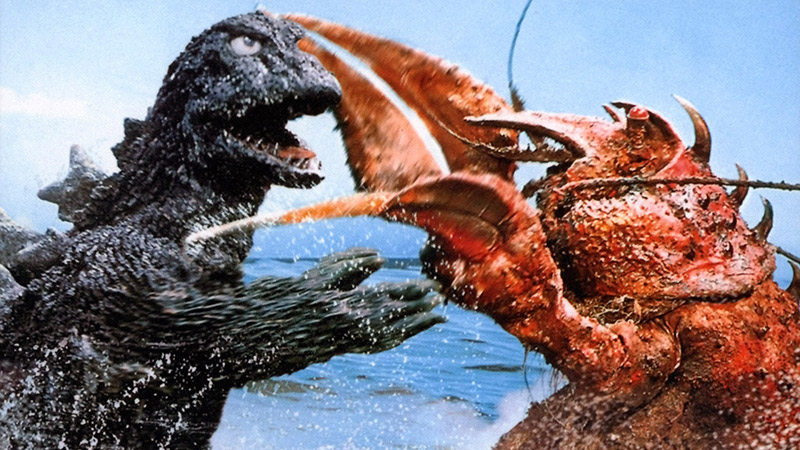

Kaijū Equivalent: Ebirah

Japanese spider crabs have the longest leg-span of any living arthropod (the phyla that contains crustaceans, insects, and arachnids) with some specimens reaching up to 3.8 meters. That’s twelve feet of either terrifying spider legs or good eating depending on your level of arachnophobia. They are most common on the southern coasts of Honshū at shallows of 160 feet all the way down to 2,000 feet or more, usually preferring trenches and dark crevices. They typically scavenge the ocean floors for plants, algae, shell fish, or animal carcasses. I suppose it’s not too much of a stretch to imagine them towering over a beach-front village, combing the streets for fleeing citizens to snatch into their claws.

#9: Blue Whale

Kaijū Equivalent: Godzilla

This one’s a bit of a cop-out, but I would be remiss not to include the largest living animal in the world and the heaviest creature to have ever existed in a list of giant monsters. This monstrous creature has a large range of habitats with subspecies existing in all major oceans. In Japan, these gigantic creatures have inspired awe for a long time—not only are they half of Godzilla but they are the inspiration for many bakekujira (monster whale) myths. In waters near Japan, whaling has decreased their population, but they are still one of the undisputed kings of the deep and a definite contender for the real-life kaijū throne.

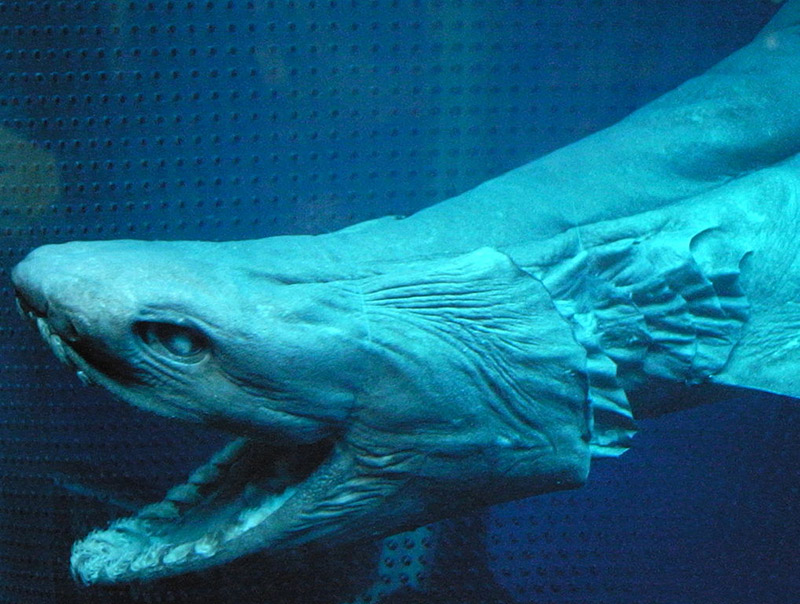

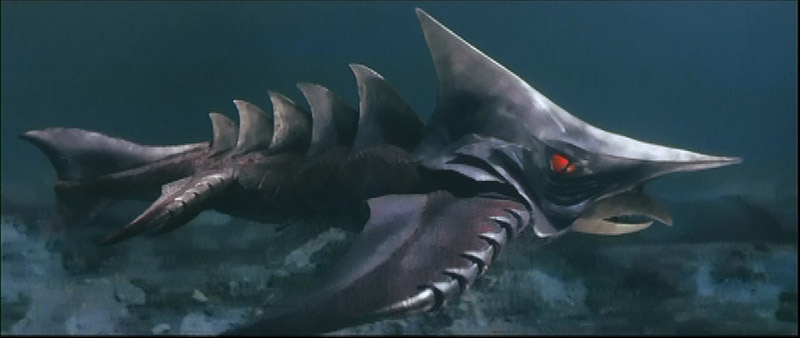

#8: Frilled Shark

Kaijū Equivalent: Zigra

After this we’re done with the deep sea kaijū and we’re setting foot on the dry land. Considering that a common thread of kaijū movies is mutation from prehistoric creatures, I figured a species that can be considered a living fossil would be fair game. The first one to be videotaped alive in approximately all of human history made quite a splash in 2007, no pun intended, when it was captured off the coast of Japan.

He was pretty sickly looking, which makes sense as he was so far from home. These guys like to be deep, deep, underwater. We’re talking 5,150 feet deep, the deepest that a frilled shark has ever been recorded. These remarkable oddities have several things in common with both prehistoric shark species and their modern-day descendants, which makes them quite the living fossil. Despite their rarity to human eyes, these sharks have been given the conservation status of “not threatened” due to their widespread distribution and the presumably large population that is hard to measure in the darkest depths of the sea. Pretty spooky thinking about the kind of things that can hide from us in the ocean; this guy hid for so long we could’ve sworn he was extinct! Due to this creatures serpentine body, some cryptozoologists even posit that there is a larger cousin of this guy nestled in the deep that explains modern-day sightings of sea serpents.

#7: Sika Deer

Kaiju Equivalent: Cowra

Kaijū just means “strange beast”, it doesn’t mean “giant beast”. When it comes to strangeness and quirkiness, these deer can definitely be considered kaijū in their own right. Take into account, for example, that these are some quintessentially Japanese deer. Their English common name comes from the Japanese shika 鹿 meaning deer. They’re so Japanese that, in Japan, they are called simply nihonjika 日本鹿. They used to be common all over Eurasia from Russia to China and back again but, over time, they became extinct everywhere except Japan where they are overly abundant.

Japan, one of the only places in the world that didn’t hunt them for their antler velvet, quickly became the haven of the Sika Deer. These deer outlived their only known predators in Japan, the Japanese wolves, which were extinct by 1905. Unique habitat, no known enemies, sound kaijū-ey enough for ya? Not yet? Okay. Their genus is cervus or “true deer” of which there are now only a handful of species. Not only are they the most Japanese deer they are also among the deeriest of deer.

#6: Amami Rabbit

Kaijū Equivalent: Hanejiro

This is another kaijū that might take some convincing to be seen as such, but there is something truly remarkable about this living fossil. It is now only found in two small islands, Amami Ooshima and Toku-no-Shima in Kagoshima Prefecture. This rabbit contains many characteristics from Miocene-era fossils of rabbits and hares such as small eyes and a long snout. The Amami rabbit’s appearance is so primitive and distinct from modern day rabbits that, if you happened to see one hopping about, you might not even know what you are looking at.

#5: Okinawa Habu

Kaiju Equivalent: Dai Umi Hebi

Habu is a common name given to venomous snakes in Japan, particularly pit vipers. The Okinawan Habu is the largest snake species in Japan and tied with the mamushi for the most venomous. Ranging from 4 to 8 feet long, this snake is several times larger than the Japanese rat snake, which is the largest Japanese snake outside of Okinawa. On islands where these vipers are plentiful, they are commonly collected for making awamori (a traditional Okinawan alcohol similar to sake). The resulting habu sake is often sold with the snake pickled in the bottle for dramatic flair. Snake wines like these were popular in Asia for a long time as folk medicine. Nowadays, they make for one heck of a souvenir. If you are ever in Okinawa and want to buy some of this wine or learn more interesting facts about these bad mamma-jammas, check out the Habu Museum Park.

#4: Ryukyu Flying Fox

Kaijū Equivalent: Kyuranos

Whenever the term flying fox gets thrown around, I get excited. Some flying foxes can be as large as medium-sized dogs, so the term flying fox is very apt. If a dog-beast flying on leathery wings isn’t kaijū enough for you I don’t know what is. Unlike Kyuranos, however, the only flesh these guys want to sink their teeth into is that of a pear, or perhaps the occasional insect. Flying foxes are large fruitbats that are considered to be megabats. They are important pollinators in the wilds of Ryukyu where they act as giant fanged hummingbirds. As their cousin in Okinawa is already extinct, it makes sense that these guys are on the conservation list.

#3: Ussuri Brown Bear

Kaijū Equivalent: King Caesar

The story of the Ussuri brown bear in Japan is probably the closest thing to a giant monster movie that one will encounter in real life. And why not? This ancestor of the grizzly bear can weigh up to 1,400 pounds and is the largest land animal that inhabits Japan. It is currently considered endangered due to loss of habitat, but it was once the terror of Hokkaido. The indigenous Ainu people of Japan worshipped the Ussuri bear because of its strength and vigor. In a festival called Iomante a new-born brown bear would be raised for a few years in an Ainu village while being treated to the finest food and amenities they could provide. The bear was treated like a god. After the bear reached two years of age, they would tie it to a public post in the village and kill it with arrows and clubs—uh…like a god? After the bear was dead they would skin it, distribute the furs and meat, drink the blood for vitality, and use the skull as an ornament of continued worship.

So for those of you keeping track, the Ussuri brown bear has 1. “worshipped by a native population”, and 2. “attack villages and eat people”.

That’s about as kaijū as you can get. From the year 1900 to around 1957, when the bears were more plentiful, they were responsible for 141 deaths and over 300 injuries. The most high-profile event came to be known as the Sankebetsu Brown Bear Incident (3. “have an incident named after you”) where, for five days in 1915, a large brown bear stalked and terrorized the recently-settled Tomamae village in Hokkaido. The bear awoke from hibernation to find people where he was pretty sure he didn’t see people before and then set out return his habitat to normal. He stole grain at first, as if demanding tribute, and then started munching through people like it was going out of style—claiming seven victims across the attack. He even popped in during the pre-funeral rites for the first victims just to rub it in. Experienced hunting parties went after the bear, now nicknamed Kesagake 袈裟懸け or “diagonal shoulder slash,” his apparent calling card. For days the nearly 9 foot tall and 800 pound bear eluded the hunters, but was eventually brought to justice. The bear even created a redemption story for the son of the mayor of Tomamae village who swore to kill ten bears for every victim of the attack, and ended up overachieving. There have been novels, radio plays, manga, and film adaptations of this story making this kaijū’s legacy come full-circle. These giant beasts have had an intense and blood-soaked history with the Japanese and, though their numbers are now in decline, they can still be considered among the biggest and baddest of Japan’s real-life kaijū.

#2: Japanese Giant Salamander

Kaijū Equivalent: Japanese Giant Salamander (Sanshouuo Kaijin)

The Japanese giant salamander is one of the true natural wonders of Japan’s rivers and streams. These suckers can grow to sizes of around 5 feet in length and weigh up to 60 pounds. In fact they are the second largest amphibian in the world, the only thing bigger than these guys is their Chinese subspecies. They are so large that they were once fished as a food source by the local people. Now they are protected by law, but it’s bizarre to think of using a salamander as a primary food source when most species would barely qualify as a snack. The Japanese giant salamander remains amphibious for its entire lifespan. Even when these monsters reach adulthood and lose their gills, they are large enough to simply pop their heads above water whenever they want air.

They are carnivorous and nocturnal, so they hide under rocks during the day and at night and will lumber around streams, waiting to suck prey into their mouths. Their eyes are small and underdeveloped and find their prey by using tiny hairs on their body to sense ripples and vibrations in the water. When they catch their meal, they don’t even need to chew. Since they feed underwater, they don’t produce saliva. They do, however, secrete a strong musk as a defense mechanism that has the reputation for smelling like the Japanese pepper plant, thus their Japanese common name oosanshouuo 大山椒魚 or “giant pepper fish.”

Considering their strange lifecycle and features, it’s no wonder they were originally thought of as a fish. They even swim upstream to spawn and males fertilize eggs externally in huge clutches—just like fish. Japanese giant salamanders are a national treasure and have inspired art and folklore since they were first discovered. There’s even speculation that myths about kappas originated out of fear of these watery critters.

#1: Japanese Giant Hornet

Kaijū Equivalent: Battra

Finally, the most monstrous beast in all of Japan is the Japanese giant hornet. You might be wondering, why out of all the crazy animals we’ve seen on this list, the number one kaijū is only two inches long. Because it is two inches long! Sporting a two and a half inch wing-span and quarter-inch (or longer) stinger, Japanese giant hornets are a nightmare.

While the venom they inject isn’t the most deadly of hornet venoms, it is quite a lot considering their size. Yes, the Japanese giant hornet has truly earned it’s place as the king of Japanese kaijū.

For starters, they are the deadliest animal in all of Japan. Their stings claim thirty to forty lives every single year, second to them are the venomous snakes that kill five to ten people a year, while the big bears of the highlands only cause between zero and five fatalities. But it’s not just their impact on humans that gives them the kaijū throne, it’s what they do to other bees. When these hornets find themselves displaced in Europe or the Americas, or when Japanese beekeepers use European honeybees in the interest of increasing their yield, those bees better watch their backs. Japanese giant hornets ruthlessly and systematically destroy honeybee hives, it’s just how they roll.

To the poor honeybees, these hornets are like dragons attacking a castle and they waste no time ransacking it. It only takes a handful of hornets to demolish a thriving population of European honeybees. The hornets bite, sting, and use their legs to dismember their prey. This way they can selectively take the best parts for their dinner. Not only that, but when given the chemical signal, they will opportunistically ignore lesser prey to raid larvae, pupae, or the queen’s supply of honey. Giant hornets make unflinchingly conniving nest invaders. The only reason that these guys haven’t wiped out all of the honeybees in Japan (something that they could actually do to the Western world if their populations started booming) is because the Japanese honeybees have co-evolved with the massive predators to develop a very sly countermeasure.

As seen in the video above, it takes an entire hive working together and the sacrifice of a honeybee martyr for these tiny bees to take out just one of the would-be usurpers, but it’s either that or lose the hive. Really, when you think about it, the hornet’s own size and heavy exoskeleton are the things that cause the temperatures to rise to that critical self-cooking level. So, in a way, the only thing that can stop these hornets is themselves. This is the apex predator of the insect kingdom. And let’s have a shout-out to the Japanese honeybees for trying to survive in the face of a killing machine like this. I , for one, welcome our new six-legged kaijū overlords.

Well, there you have it folks. The top ten biggest, toughest, weirdest, and cutest animals that deserve to be considered true-to-life kaijū of Japan.