Rendaku, also known as "sequential voicing" in English, is an aspect of the Japanese language you've almost certainly come across, no matter what your level of Japanese. Have you learned any of these words?

- ひとびと (people)

- てがみ (letter)

- はなび (fireworks)

- ひらがな (hiragana)

If so, you've already seen rendaku in action. Rendaku happens when two or more words join together to form one word, and the initial consonant of the second word becomes voiced. (In written form, it gets the little dakuten or handakuten mark.) That's rendaku!

Perhaps you asked your Japanese teacher why 人々 is ひとびと and not ひとひと. Or maybe you asked why はんはん doesn't change to はんばん. To these questions, you probably received a sigh and one of the following answers:

It's random.

Japanese tutor

You just have to memorize them.

Japanese professor

Yet another unsatisfactory response.

A typical Japanese textbook

- 連濁(れんだく)

- When two or more words come together to form a compound, and the first consonant in the second word becomes voiced.

But it doesn't have to be this way! There are rules and patterns. And theories, lots of them. Trouble is, none of them do a great job of showing the whole picture. Some have explanations we were able to disprove by ourselves with very little effort. By combing through them all, we were able to put together a guide that actually makes sense.

If you read our guide, you'll be able to predict (or at least understand) why certain words receive the rendaku treatment most of the time. Even if you're just a beginner of Japanese, you'll be able to understand a surprising amount. Plus, it will answer your nagging ひとびと questions.

Prerequisites: This article is going to use hiragana and katakana, and discuss some advanced linguistic concepts. While you don't need to read the entire guide to get a basic understanding of rendaku, it will still be helpful. Just know things may get pretty "in the weeds" for you language lovers.

- Voicing

- Compound Words

- What is Rendaku?

- General Rendaku Rules

- Lyman's Law

- Lexical Complications

- Dvandva / Copulative Compounds

- Onomatopoeia

- Prefixes and Suffixes

- Rendaku-Lovers

- Common Mistakes and Exceptions

- Practice Your Rendaku!

Before you move on: check out the podcast we recorded about rendaku. It covers some of the topics below and there's even a quiz at the end so you can test your knowledge (and see if you know more about rendaku than we do).

Or you can just subscribe to the Tofugu Podcast and save it for later, as a review of the knowledge you're about to gain from this article.

Now, let's take care of a little housekeeping. You'll need to learn two important concepts used throughout this guide.

Voicing

All languages make use of voiced and unvoiced sounds. When you make a voiced sound, the vocal cords inside your larynx vibrate; when you make an unvoiced sound, they don't. Although this seems simple, we recommend you read more about voicing in our Japanese Pronunciation Guide before you move on to the next part.

For now, the most important thing to remember is:

- Voiced = vocal cords

- Unvoiced = no vocal cords

All languages make use of voiced and unvoiced sounds.

While all English and Japanese vowels are voiced, consonants can be either voiced or unvoiced.

かきくけこ and さしすせそ are unvoiced consonants (k, s) with voiced vowels (a, i, u, e, o) attached to them.

まみむめも and らりるれろ are voiced consonants (m, r) with voiced vowels (a, i, u, e, o) attached to them.

In most cases, there is no way to tell if a consonant is voiced or unvoiced (unless you look it up or make the sound and check to see if your throat vibrates). However, there are four sets of kana characters specifically marked for their voicing, and they're all followed by a little symbol called a dakuten.

゛dakuten

Here's how they work:

Take one of the four special, voiceless consonants (k, s, t, h) and add dakuten to create a new, voiced consonant.

k → g

かきくけこ → がぎぐげごs → z

さしすせそ → ざじずぜぞt → d

たちつてと → だぢづでどh → b

はひふへほ → ばびぶべぼ

There's also an extra pair that can turn into an additional unvoiced set:

h → p

はひふへほ → ぱぴぷぺぽ

While the p sound isn't voiced in Japanese, it's considered somewhere between voiced and unvoiced. The little round circle here is called a handakuten.

゜handakuten

Dakuten and handakuten are extremely important when it come to understanding rendaku. Before we go further, however, there's one more thing you need to know.

Compound Words

A compound word is a single word made up of two or more different words. English has them too. Here are some common compound words you already know:

| Word 1 | Word 2 | Compound Word |

|---|---|---|

| air | plane | airplane |

| fire | fly | firefly |

| foot | ball | football |

| forty | two | forty-two |

| bread | winner | breadwinner |

| vegan | friendly | vegan-friendly |

| self | control | self-control |

| day | dream | daydream |

Both words exist on their own separately, but when they come together they create a new, unique word. The compound word they create can serve almost any function—noun, adjective, verb, etc. The same is true for Japanese:

| Word 1 | Word 2 | Compound Word |

|---|---|---|

| 金 (きん) | 魚 (ぎょ) | 金魚 (きんぎょ) |

| gold | fish | goldfish |

| 美 (び) | 人 (じん) | 美人 (びじん) |

| beautiful | woman | beautiful woman |

| 昼 (ひる) | 寝 (ね) | 昼寝 (ひるね) |

| noon | sleep | nap |

| 飛ぶ (とぶ) | 込む (こむ) | 飛び込む (とびこむ) |

| jumping | go into | to jump into |

| 四十 (よんじゅう) | 二 (に) | 四十二 (よんじゅうに) |

| forty | two | forty-two |

| 副 (ふく) | 大統領 (だいとうりょう) | 副大統領 (ふくだいとりょう) |

| vice | president | vice president |

Japanese compound words are pretty obvious (and there are a lot of them!), although it may only seem this way because we're studying Japanese so closely. Regardless, with these concepts in mind, let's learn what rendaku actually is.

What is Rendaku?

連濁 (れんだく) Rendaku is when two or more words come together to form a compound, and the first consonant in the second word becomes voiced. In linguistics, this is called "sequential voicing."

Let's begin with a classic example:

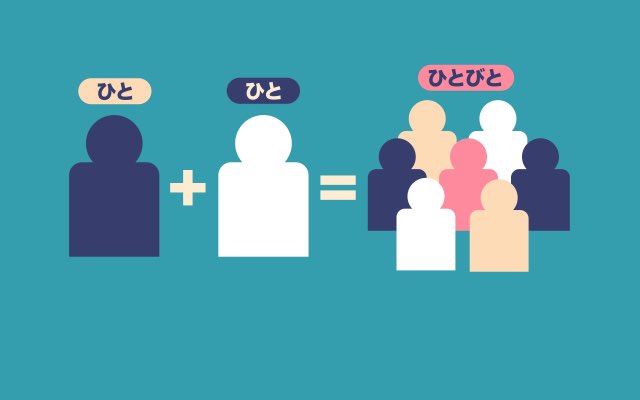

人 (ひと) + 人 (ひと) = 人々 (ひとびと)

person + person = people

Two words (ひと and ひと) come together to form the compound ひとびと. The first consonant (h) in the second word (ひと) becomes voiced (ひ → び), making it ひとびと.

Here's another example:

手 (て) + 紙 (かみ) = 手紙 (てがみ)

hand + paper = letter

Same thing: two words (て and かみ) join together to form the compound word てがみ. The first consonant (k) of the second word (かみ) becomes voiced (か → が), making it てがみ.

Using these two examples as guides, here are the basic conditions necessary for rendaku:

- Two words come together to form a compound word.

- The first consonant of the second word (before it's combined) is unvoiced.

- The first consonant of the second word is one of the four sets of characters that can change into a voiced consonant with dakuten or handakuten (k, s, t, or h).

- Surrounding the first consonant of the second word are voiced vowels (and sometimes nasals).

Let's try it out. Take a look at ひと+ひと:

- ひと and ひと are coming together to form a compound.

- The ひ in the second consonant ひと is unvoiced.

- The ひ in the second consonant ひと is one of our unvoiced consonants: h.

- H is surrounded by voiced vowels: the o in と and the i in ひ.

The result? Rendaku! ひとびと!

A word of caution, however. Just because the conditions are right for rendaku doesn't mean a word will always rendaku. There are other, more specific rules. This guide starts broad and focuses in on the specifics. Even if you only read the first half of this article, you'll probably be good 60–70% of the time. (That being said, we think you should read the whole thing! 😡)

B or P

One quick note before we move on to our rules. Let's talk about the h sound in Japanese. Since h can change to either b or p, you may have wondered why ひとびと changed to びと and not ぴと. As it turns out there's actually a rule for this:

If the first word ends in つ or ん the h consonant will usually rendaku to p.

Everything else defaults to b.

Here are a few examples:

出 (しゅつ) + 発 (はつ) = 出発 (しゅっぱつ)

exit + departure = departure

しゅつ shortens into しゅっ and はつ becomes ぱつ. The sokuon (促音), also known as the small tsu, is what causes h to become p.

鉛 (えん) + 筆 (ひつ) (えんぴつ)

lead + writing brush = pencil

ひつ becomes ぴつ. The ん causes h to become p.

Keep this relationship between h, b, and p in mind as you go through the rest of the guide. You'll see examples of it popping up again and again.

General Rendaku Rules

Rendaku can be difficult to understand because it's riddled with exceptions and can be unpredictable.

Below is a list of the general rules rendaku tends to follow. We'll go into each one in detail using the three E's: explanations, examples, and exceptions.

WARNING: While we are calling these "rules," they're more like guidelines. Rendaku can be difficult to understand because it's riddled with exceptions and can be unpredictable. These "rules" exist to help you get a better idea of how and when to predict rendaku, but they're in no way absolute or unbreakable. Language is tricky like that.

- Japanese origin words do rendaku.

- Chinese origin word do not rendaku.

- Foreign loanwords do not rendaku.

- If the second word in the compound has a voiced consonant or handakuon anywhere in it, rendaku does not occur.

- If voicing in the first word is too close to the second word, rendaku may not occur.

- In words that come together to mean "X and Y," rendaku does not occur.

- Repeating onomatopoeia do not rendaku.

- Certain prefixes and suffixes cause rendaku not to occur.

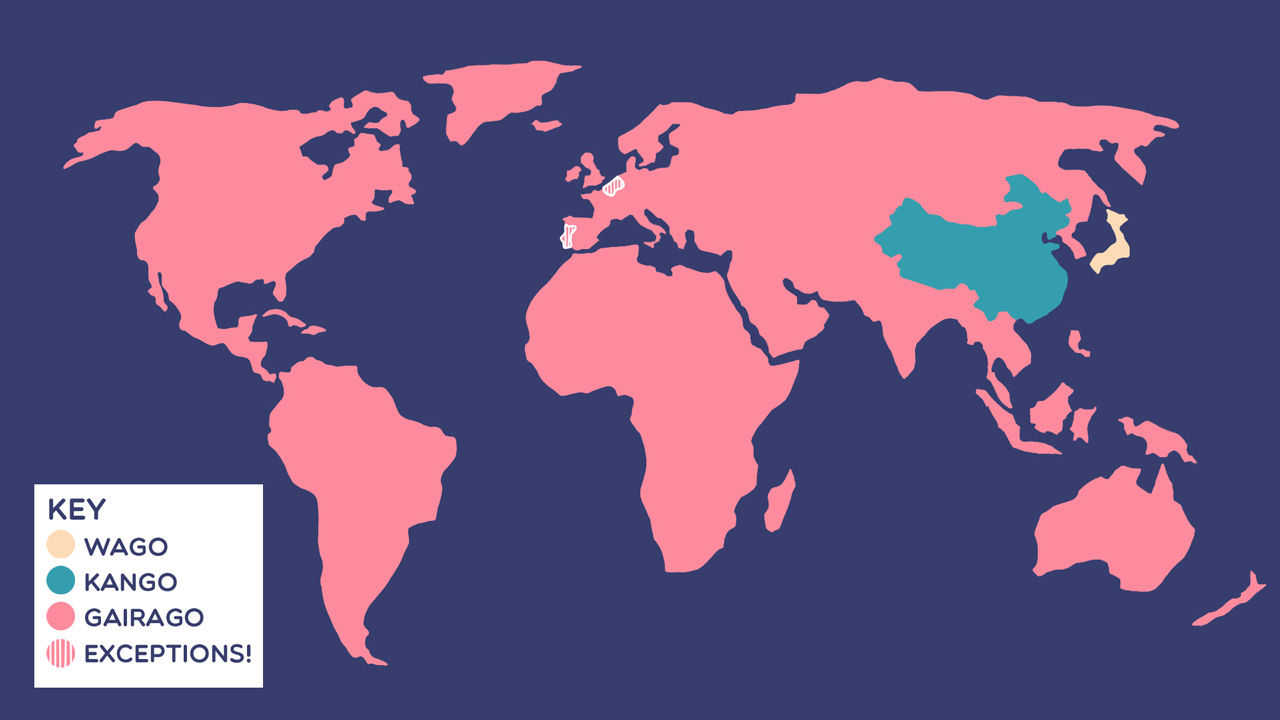

Before we go through each of those rules one by one, let's start with a quick lesson about Japanese's three word categories (which affect rules 1–3).

- Wago (和語) - native Japanese words

- Kango (漢語) - Chinese loanwords

- Gairaigo (外来語) - foreign loanwords

Wago, also known as Yamato Kotoba (大和言葉), covers all words inherited from old Japanese. They weren't borrowed, adapted, or introduced from any other language. They're real Japanese, through and through.

Kango are words introduced from China over many centuries, then changed and adapted to fit Japanese pronunciation rules.

When we talk about kanji readings, we use the terms kun'yomi (訓読み) for native Japanese readings (wago) and on'yomi (音読み) for readings derived from Chinese (kango). Kanji reading history and usage is very interesting, and will help you to understand rendaku even better. If you haven't already, we'd suggest giving our On'yomi and Kun'yomi Guide a read before continuing.

Gairaigo are words that were introduced from countries other than China. Nowadays, most of these exist as katakana loanwords, but the Dutch and Portuguese languages had a strong influence in Japan's Edo period (1603–1868), before loanwords were being katakana-ized. These are trickier to spot and usually appear in kanji or hiragana.

Now you're ready to move forward.

Japanese Origin Words Do Rendaku

We're going to start with wago: the words native to Japan. One thing to know about these words is that, barring a few exceptions, they almost never start with a dakuten or handakuten voiced consonant (g, z, d, b, p), and those that do are super rare.

This means rendaku was probably originally a natural, unintentional way to distinguish compound words from saying a word twice, comparing two words, or listing things. Words like ひとびと make it clear you aren't saying 「ひと、ひと」 (a person, another person), and everyone would know びと isn't a word, because real words don't start with び!

Let's look at a few examples:

草 (くさ) + 花 (はな) = 草花 (くさばな)

grass + flower = flowering plant

くさばな indicates that you aren't talking about grass and flowers, and ばな isn't a word on its own.

青 (あお) + 空 (そら) = 青空 (あおぞら)

blue + sky = blue sky

あおぞら lets you know you know this is a compound in which "blue" is modifying "sky." Also, ぞら isn't a word.

Looking again at our list of ideal conditions for rendaku, we can see that Japanese words are the perfect catalysts.

- Two words come together to form a compound word.

- The first consonant of the second word is unvoiced.

- The first consonant of the second word is one of the four sets of characters that can change into a voiced consonant with dakuten or handakuten (k, s, t, or h).

- Surrounding the first consonant of the second word are voiced vowels (and sometimes nasals).

Almost all wago words start with unvoiced consonants, and all vowels are voiced. That means if the second word in the compound starts with k, s, t, or h, the conditions for rendaku are perfect! Take a look at the following examples, confirming that 1–4 on the list above apply.

k → g

平 (ひら) + 仮名 (かな) = 平仮名 (ひらがな)

flat + kana = hiraganas → z

山 (やま) + 桜 (さくら) = 山桜 (やまざくら)

mountain + cherry blossoms = wild cherry blossomst → d

鼻 (はな) + 血 (ち) = 鼻血 (はなぢ)

nose + blood = nosebleedh → b

花 (はな) + 火 (ひ) = 花火 (はなび)

flower + fire = fireworksh → p

出 (で) + 歯 (は) = 出っ歯 (でっぱ)

exit + tooth = buck teeth

The Japanese language was happily rendaku-ing like this until about the 4th century. Those of you who have read up on your on'yomi and kun'yomi history already know what's coming, but for the rest of you… this is when China shows up on the scene.

Chinese Origin Words Do Not Rendaku

The power of these kango words is so strong that they even have the habit of stopping rendaku from happening.

Unlike wago, kango words derived from Chinese can and do start with voiced consonants. Because of this, applying rendaku would cause unvoiced consonant words to sound like other voiced consonant words and result in confusion.

For example, in the word 入学試験 (にゅうがくしけん), which means "school entrance examination," you would not rendaku it to にゅうがくじけん. If you did, it might be confusing, because じけん (事件) means "incident." As in: "Oh my god, did you hear about the school entrance incident?"

Clearly that's not what you meant to say.

Similarly, the さっか in 放送作家 (ほうそうさっか), which means "broadcast writer," wouldn't have rendaku applied to the さっか. If it did, we'd get ざっか, which sounds like the word 雑貨, or "miscellaneous."

You're probably starting to understand why Chinese kango words don't rendaku. There is too much ambiguity, at least when compared to wago words. This high probability for misunderstanding is most likely why kango compound words do not rendaku, for the most part. These kanji compound words, made up of two or more on'yomi readings are called jukugo (熟語), and only a small percentage of them rendaku.

The power of these kango words is so strong that they even have the habit of stopping rendaku from happening, even when they're in a compound with a Japanese word.

In kango + wago words, where the first element uses the on'yomi reading and the second element uses the kun'yomi reading, rendaku can be blocked. Even if all of the other conditions for rendaku exist, the kango word will still stop it from occurring.

Let's look at how this works:

梅 (うめ) + 干し (ほし) = 梅干し (うめぼし)

plum + dry = pickled dry plum

Both words above are wago and use the kun'yomi readings. And because the conditions are right, the ほ becomes ぼ.

布団 (ふとん) + 干し (ほし) = 布団干し (ふとんほし)

futon + dry = drying a futon

ふとん, however, is a kango word that uses the on'yomi readings and ほし is a wago word using the kun'yomi readings, so ほ does not rendaku.

"But wait," you're probably saying, "the ん in ふとん isn't a voiced vowel!" No, it's not, but it is a nasal sound, which doesn't stop rendaku.

川 (かわ) + 底 (そこ) = 川底 (かわぞこ)

river + bottom = riverbed心 (しん) + 底 (そこ) = 心底 (しんそこ)

heart + bottom = bottom of your heart奥 (おく) + 底 (そこ) = 奥底 (おくそこ)

interior + bottom = depths

そこ is a wago word, and it does rendaku in a compound word with another wago word (かわ). But it doesn't when paired with kango words (しん and おく).

The word 大 is another good example of a kango word that stops rendaku completely:

大(だい) + 好き (すき) = 大好き (だいすき)

big + like = love

だい is kango and すき is wago, but すき does not rendaku.

However, in wago + wago word pairs, you often see すき rendaku:

好き (すき) + 好き (すき) = 好き好き (すきずき)

like + like = matter of taste話し (はなし) + 好き (すき) = 話し好き (はなしずき)

talk + like = talkative person酒 (さけ) + 好き (すき) = 酒好き (さけずき)

alcohol + like = drinker

And then you have:

大 (だい) + 嫌い (きらい) = 大嫌い (だいきらい)

big + dislike = hate

だい is kango and きらい is wago, but きらい does not rendaku. And, similar to すき, wago + wago combinations do see きらい rendaku.

犬 (いぬ) + 嫌い (きらい) = 犬嫌い (いぬぎらい)

dog + hate = dog hater猫 (ねこ) + 嫌い (きらい) = 猫嫌い (ねこぎらい)

cat + hate = cat hater女 (おんな) + 嫌い (きらい) = 女嫌い (おんなぎらい)

woman + hate = misogyny

That doesn't mean all kango compounds don't rendaku though. Rendaku also occurs in kango sometimes, especially if the second element is vulgarized. Vulgarization, in the linguistic sense, simply means to make a word common. Because it's part of the general language, it's treated like it is a wago word.

Let's look at some examples:

夫婦 (ふうふ) + 喧嘩 (けんか) = 夫婦喧嘩 (ふうふげんか)

married couple + fight = fight between a married couple

This kango compound has become a general term in the Japanese language. And even though it's made up of two on'yomi words, the second word does rendaku. 喧嘩 has become such a common word in Japanese that it now receives the rendaku treatment quite a bit.

兄妹 (きょうだい) + 喧嘩 (けんか) = 兄妹喧嘩 (きょうだいげんか)

siblings + fight = fight between siblings内輪 (うちわ) + 喧嘩 (けんか) = 内輪喧嘩 (うちわげんか)

family circle + fight = family feud

In the next two examples, we will see wago + kango compound words. Because of how common/vulgarized the kango word is, it's treated as though it's wago, allowing it to rendaku.

株式 (かぶしき) + 会社 (かいしゃ) = 株式会社 (かぶしきがいしゃ)

stocks + company = public corporation青 (あお) + 写真 (しゃしん) = 青写真 (あおじゃしん)

blue + photo = blueprint

In the next three examples, we see a kango + wago combination. Since these kango words are vulgarized, they are treated like they're wago, which means the second word can rendaku even though the first word is kango.

野 (の) + 菊 (きく) = 野菊 (のぎく)

field + chrysanthemum = wild chrysanthemum避難 (ひなん) + 梯子 (はしご) = 避難梯子 (ひなんばしご)

escape + ladder = fire escape ladder座 (ざ) + 布団 (ふとん) = 座布団 (ざぶとん)

sit + futon = flat floor cushion

Other examples of vulgarization may not be as obvious at first. Consider the following kango words:

中 (ちゅう) + 国 (こく) = 中国 (ちゅうごく)

middle + country = China韓 (かん) + 国 (こく) = 韓国 (かんこく)

Korea + country = Korea

Unlike wago, kango words derived from Chinese can and do start with voiced consonants.

Why does 中国 rendaku but 韓国 doesn't? This is one of the most frequently asked rendaku questions, and there are a few possible answers.

First, if you see 中 by itself, you wouldn't necessarily think of "China," because by itself it's also used for "middle" or "center;" it has to be combined with 国 to mean China. However, if you see 韓 by itself, you'll always know it's "Korea," because that's almost always how it's used.

Also, the stronger it feels like one word instead of a two word compound, the more likely that word is to rendaku. 韓国 doesn't need the 国 to mean "Korea," which makes the combination less likely to rendaku.

Another possible reason is simply because of the misunderstandings we talked about earlier.

中国 without rendaku could be confused for 忠告 (ちゅうこく), meaning "advice" or "warning."

韓国 with rendaku could be confused for 監獄 (かんごく), meaning "prison."

When you look at it this way, it's much easier to see why some kango rendaku and others don't. It merely takes some research to find out why.

These reasons—whether kango undergoes rendaku or not—are still being researched, so they're just theories. Maybe someday we'll have a real linguistic solution and rules to follow. But for now, this is what we've got!

Foreign Loanwords Do Not Rendaku

Gairaigo, foreign loanwords from everywhere but China, are usually written with katakana, and katakana loanwords almost never rendaku.

アイス + コーヒー = アイスコーヒー

ice + coffee = iced coffee

You wouldn't change コーヒー to ゴーヒー, because the word you're adapting is iced coffee, not iced goffee!

ガラス + ケース = ガラスケース

glass + case = glass caseカラー + テレビ = カラーテレビ

color + tv = color tv

The same goes for katakana loanwords that combine with wago words to form compounds.

眼鏡 (めがね) + ケース = 眼鏡ケース (めがねケース)

glasses + case = glasses case生 (なま) + ハム = 生ハム (なまハム)

unprocessed + ham = uncured ham

While most katakana loanwords are Western words, gairago still refers to any and all loanwords that aren't from China. Most non-katakana gairaigo comes from Portuguese or Dutch and, unfortunately, because they've been in the language for so long (sometimes hundreds of years), they can rendaku too. They're pretty rare, but let's take a look at the most common ones:

雨 (あま) + 合羽 (かっぱ) = 雨合羽 (あまがっぱ)

rain + coat = raincoat

あま is wago, but かっぱ is a loanword derived from the Portuguese word capa, meaning "coat." This word has been vulgarized and become a general-use term, so it does rendaku.

いろは + かるた = いろはがるた

iroha order + cards = iroha karuta

いろは is a term for the oldest Japanese syllabary (like aiueo order), and かるた is a loanword derived from the Portuguese carta, meaning "card." Like 雨合羽, this word has been vulgarized into general use, so it also undergoes rendaku.

Note that unlike blocking rendaku, like kango does, gairago + wago can cause rendaku, just like a normal wago word. Just because the gairaigo itself doesn't rendaku doesn't mean gairaigo stops normal wago from doing so.

ビー + 玉 (たま) = ビー玉 (ビーだま)

glass + ball = marble

The ビー in ビー玉 is a shortened form of ビードロ, the Portuguese loanword from vidro, meaning "glass." Add it to the wago word for "ball," and it does rendaku.

ズック + 靴 (くつ) = ズック靴 (ズックぐつ)

canvas + shoes = canvas shoes

ズック is the loanword from the Dutch word doek, meaning "canvas" or "cloth." Add it to the wago word for "shoes" and it does rendaku.

The need for rendaku exists in more modern, Western compounds as well:

ハート + 形 (かた) = ハート形 (ハートがた)

heart + shape = heart shapeボール + 紙 (かみ) = ボール紙 (ボールがみ)

cardboard + paper = cardboard paper

Now that you know where these words are coming from and how they affect each other, it's time to talk about other ways to predict whether a word gets the rendaku treatment or not. As it turns out, there are many different variables that can affect rendaku. It isn't simply based on where that word originated or how long it's been in the Japanese language.

Lyman's Law

Lyman's Law is probably the most well-known method people use to figure out whether a word will rendaku or not. While its name comes from a late-1800s linguist named Benjamin Smith Lyman, it was actually first discovered in Japan by an Edo period linguist, Kamo no Mabuchi (賀茂真淵).

Lyman's Law states that:

Rendaku does not occur when the second element of the compound contains a voiced obstruent in any position.

An "obstruent" is a voiced consonant or handakuon consonant. That means rendaku won't occur if the second word already has a voiced consonant or handakuten in it—i.e., it doesn't start with g, z, d, b, or p.

Here are some examples:

人 (ひと) + 人 (ひと) = 人々 (ひとびと)

person + person = people

The second word (ひと) does not have a voiced consonant, so it does rendaku.

時 (とき) + 時 (とき) = 時々 (ときどき)

time + time = sometimes

Similarly, the second word (とき) does not have a voiced consonant, so it does rendaku.

山 (やま) + 火事 (かじ) = 山火事 (やまかじ)

mountain + fire = forest fire

The second word (かじ) does have a voiced consonant: かじ, so it does not rendaku.

紙 (かみ) + 屑 (くず) = 紙屑 (かみくず)

paper + waste = wastepaper

The second word (くず) does have a voiced consonant: くず, so it does not rendaku.

春 (はる) + 風 (かぜ) = 春風 (はるかぜ)

spring + wind = spring wind

The second word (かぜ) does have a voiced consonant: かぜ, so it does not rendaku.

おお + とかげ = おおとかげ

big + lizard = big lizard

Lyman's Law is probably the most well-known method people use to figure out whether a word will rendaku or not.

By now you've figured it out: the second word (とかげ) does have a voiced consonant: とかげ, so it does not rendaku.

Theories have popped up over the years as to why this pattern of avoiding two voiced consonants in one word exists, but the most common among them point out that it's just plain hard to pronounce certain words together. Other reasons include:

- To avoid double nasal sounds (1972)

- Two voiced consonants in a row don't exist in wago (1977)

- Two voiced consonants in a single word don't exist in wago (1988)

Regardless of why it exists, Lyman's Law will help if you're having trouble figuring out how to read a word. There are plenty of exceptions, of course, but you should be able to use it as a basis to guess at new words.

Lyman's Law, But Backwards

Before we leave Lyman, there's one exception that's very rare, but also very interesting. In some compounds, when the second word's second consonant is voiced, it can become voiceless and even switch its voicing to that of the first consonant instead. Most of the words this applies to are from classical Japanese, so there's no need to worry about them. But a few are fairly common.

舌 (した) + 鼓 (つづみ) = 舌鼓 (したづつみ)

tongue + hand drum = smacking your lips

The second consonant in つづみ has become unvoiced and the first consonant voiced: づつみ.

腹 (はら) + 鼓 (つづみ) = 腹鼓 (はらづつみ)

belly + hand drum = belly drumming

The same thing happens to つづみ here, too. Nowadays we pronounce them as したつづみ and はらつづみ, but they're not the only ones:

後 (あと) + 退ざり (しざり) = 後退さり (あとじさり)

after + step back = stepping back

後退さり is now read あとずさり, but it was originally あとじさり. It was a combination of 後 (あと) and an old verb 退ざる (しざる). The second consonant, voiced ざ, became voiceless さ; voiceless し became voiced じ. At least it follows the "two voiced consonants don't exist in a row" theories, though how they go about it is pretty bizarre!

Lexical Complications

Our second rule is similar to Lyman's Law, but it wasn't named after an old, dead, white scholar.

If voicing in the first word is too close to the second word, rendaku may not occur.

This is much less consistent, but think of it this way: Japanese doesn't really like having a bunch of dakuten and handakuten very close to each other.

Let's look at how this works with the word 玉 (たま).

赤 (あか) + 玉 (たま) = 赤玉 (あかだま)

red + ball = red ball

There is no dakuten in あか, so たま does rendaku, to だま.

百円 (ひゃくえん) + 玉 (たま) = 百円玉 (ひゃくえんだま)

hundred yen + coin = hundred yen coin

There is no dakuten in ひゃくえん, so たま does rendaku, to だま.

勾 (まが) + 玉 (たま) = 勾玉 (まがたま)

bent + jewel = comma-shaped jewel

まが has dakuten right before the second word. That's too close, so it does not rendaku.

水 (みず) + 玉 (たま) = 水玉 (みずたま)

water + ball = polka dot

みず has dakuten right before the second word. It's also too close, so it does not rendaku.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of exceptions to this rule, so we can only suggest that rendaku may not occur when you see it. It's about a 50/50 chance, so being aware of it can be helpful.

Dvandva / Copulative Compounds

Another factor that blocks rendaku from occurring is dvandva. Dvandva is the Sanskrit word for "pair," and that's exactly what these words represent.

Instead of two words coming together to form a single compound word, dvandva compound words more closely translate to adding an "and" between them. English examples of dvandva are pretty rare because we tend to break them up into separate words, but there are a few:

bittersweet = bitter and sweet

stir-fry = stir and fry

sleepwalk = sleep and walk

The "and" shows us that the relationship between the two words in dvandva compounds are equals. If it helps, think of the "and" as an "and also": bitter and also sweet. Sleep and also walk. In linguistics, this is called a copulative compound.

When two or more words come together to form a dvandva/copulative compound, the result does not rendaku.

Let's look at some examples:

山 (やま) + 川 (かわ) = 山川 (やまかわ)

mountain + river = mountains and rivers

If you are talking about mountains and also rivers, you can use the word 山川 and it does not rendaku. The relationship between mountains and rivers are equal. There aren't more mountains than rivers, they aren't modifying each other; they're the same.

But if we change the meaning a bit:

山 (やま) + 川 (かわ) = 山川 (やまがわ)

mountain + river = a mountain river

Mountain is now modifying river, the "and" relationship is gone, and it does rendaku. The relationship between mountain and river is no longer equal. Mountain becomes the adjective to river's noun and it's "a mountain river."

Consider a few more examples.

白 (しろ) + 黒 (くろ) = 白黒 (しろくろ)

white + black = black and white

White and black are equals, so they do not rendaku.

色 (いろ) + 白 (しろ) = 色白 (いろじろ)

color + white = fair-skinned色 (いろ) + 黒 (くろ) = 色黒 (いろぐろ)

color + black = dark-skinned

In these two examples, the first color is white-ish and the second color is black-ish. They are not equal, so they do rendaku. Make sense?

親 (おや) + 子 (こ) = 親子 (おやこ)

parent + child = parent and child

Parent and child are equals, so they do not rendaku.

里 (さと) + 子 (こ) = 里子 (さとご)

village + child = foster child

Foster is the type of child. They are not equal, so they do rendaku.

田 (た) + 畑 (はた) = 田畑 (たはた)

rice paddy + field = paddies and fields

Paddies and fields are equals, so they do not rendaku.

麦 (むぎ) + 畑 (はたけ) = 麦畑 (むぎばたけ)

wheat + field = wheat field

The field is made of wheat. They are not equal, so they do rendaku.

好き (すき) + 嫌い (きらい) = 好き嫌い (すききらい)

like + dislike = likes and dislikes

Like and dislike are equal, so they do not rendaku.

食わず (くわず) + 嫌い (きらい) = 食わず嫌い (くわずぎらい)

not eating + dislike = disliking something before trying it

This one should be pretty clear: not eating something but still disliking it isn't an equal relationship. They're happening in a certain order to make the meaning make sense. They are not equal, so they do rendaku.

Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia are words that represent sounds. We wrote a huge article explaining everything about them, so if you want to get in deep, start there.

Many onomatopoeia are repeating words—things like きらきら, どきどき, and わんわん. But repeating onomatopoeia do not rendaku.

くすくす represents the sound of giggling or chuckling. It does not rendaku.

しくしく represents the sound of soft crying. It doesn't, either.

くすくす represents the sound of giggling or chuckling. It does not rendaku.

きらきら represents the "sound" of sparkling or glittering. It does not rendaku.

こんこん represents the sound a fox makes. It doesn't, either.

It's important not to mix up repeating onomatopoeia sounds with repeating compound words like the ones you've seen earlier. 人々 and 時々, for example, are not onomatopoetic, so they do rendaku.

Prefixes and Suffixes

In Japanese, when you add a prefix or a suffix to a word, it technically becomes a compound word. Some prefixes block rendaku from occurring and some suffixes resist rendaku themselves. You don't need to memorize them, but knowing this can help you understand why some words don't rendaku when it seems like they should.

Here are some common prefixes. Let's see how they affect rendaku.

半 (はん) Half

半 (はん) + 半 (はん) = 半々 (はんはん)

half + half = half and half

Even if this word didn't have the blocking 半 prefix, the meaning of this word is "half and half," so there's dvandva blocking rendaku, too.

半 (はん) + 玉 (たま) = 半玉 (はんたま)

half + ball = half portion

This word came from half portions of round things (balls), like onigiri, but it can be used for half portions of noodles and fried rice as well. The 半 prefix is blocking rendaku from happening in 玉.

半 (はん) + 袖 (そで) = 半袖 (はんそで)

half + sleeve = short sleeves

Even if this word didn't have the blocking 半 prefix, the second word has dakuten, so Lyman's Law kicks in and would block rendaku anyway.

御 (お, み) Honorific

御 (お) + 箸 (はし) = 御箸 (おはし)

honorable + chopsticks = chopsticks (polite)御 (お) + 手洗 (てあらい) = 御手洗 (おてあらい)

honorable + restroom = restroom (polite)御 (み) + 心 (こころ) = 御心 (みこころ)

honorable + spirit = spirit (polite)

毎 (まい) Every

毎 (まい) + 月 (つき) = 毎月 (まいつき)

every + month = every month毎 (まい) + 年 (とし) = 毎年 (まいとし)

every + year = every year

一 (ひと) One

一 (ひと) + 口 (くち) = 一口 (ひとくち)

one + mouth = bite, gulp一 (ひと) + 葉 (は) = 一葉 (ひとは)

one + leaf = one leaf一 (ひと) + 欠片 (かけら) = 一欠片 (ひとかけら)

one + piece = fragment

二 (ふた) Two

二 (ふた) + 口 (くち) = 二口 (ふたくち)

two + mouth = Futakuchi (name)

片 (かた) One-sided

片 (かた) + 方 (ほう) = 片方 (かたほう)

one-sided + side = one side片 (かた) + 仮名 (かな) = 片仮名 (かたかな)

one-sided + kana = katakana

If you've ever wondered why ひらがな does rendaku and かたかな does not, this is why: 片 is blocking rendaku from happening.

唐 (から) China

唐 (から) + 傘 (かさ) = 唐傘 (からかさ)

China + umbrella = paper parasol唐 (から) + 衣 (ころも) = 唐衣 (からころも)

China + clothes = ancient Chinese clothes唐 (から) + 鞍 (くら) = 唐鞍 (からくら)

China + saddle = Chinese ritual saddle

白 (しろ) White

白 (しら) + 玉 (たま) = 白玉 (しらたま)

white + gem = white gem白 (しら) + 子 (こ) = 白子 (しらこ)

white + child = soft roe白 (しら) + 滝 (たき) = 白滝 (しらたき)

white + waterfall = shirataki noodles

黒 (くろ) Black

黒 (くろ) + 髪 (かみ) = 黒髪 (くろかみ)

black + hair = black hair黒 (くろ) + 子 (こ) = 黒子 (くろこ)

black + child = stagehand黒 (くろ) + 胡椒 (こしょう) = 黒胡椒 (くろこしょう)

black + pepper = black pepper

Now let's look at resistant suffixes. By "resistant," we mean they don't like to rendaku, even if the words before them would normally cause it. These suffixes are like oil to rendaku's water!

先 (さき) Previous, Tip

ペン + 先 (さき) = ペン先 (ペンさき)

pen + tip = pen nibs指 (ゆび) + 先 (さき) = 指先 (ゆびさき)

finger + tip = fingertips足 (あし) + 先 (さき) = 足先 (あしさき)

legs/feet = tips = ankles to your toes

紐 (ひも) String, Cord

腰 (こし) + 紐 (ひも) = 腰紐 (こしひも)

waist + cord = kimono cord肩 (かた) + 紐 (ひも) = 肩紐 (かたひも)

shoulder + string = shoulder strap

浜 (はま) Beach

砂 (すな) + 浜 (はま) = 砂浜 (すなはま)

sand + beach = sandy beach横 (よこ) + 浜 (はま) = 横浜 (よこはま)

side + beach = Yokohama (place name)

姫 (ひめ) Princess

舞 (まい) + 姫 (ひめ) = 舞姫 (まいひめ)

dance + princess = dancing girlもののけ + 姫 (ひめ) = もののけ姫 (もののけひめ)

Mononoke + princess = Princess Mononoke

煙 (けむり) Smoke

土 (つち) + 煙 (けむり) = 土煙 (つちけむり)

dirt + smoke = cloud of dust雪 (ゆき) + 煙 (けむり) = 雪煙 (ゆきけむり)

snow + smoke = cloud of snow血 (ち) + 煙 (けむり) = 血煙 (ちけむり)

blood + cloud = blood spray

土 (つち) Dirt

赤 (あか) + 土 (つち) = 赤土 (あかつち)

red + dirt = red clay盛 (もり) + 土 (つち) = 盛土 (もりつち)

prosper + dirt = embankment壁 (かべ) + 土 (つち) = 壁土 (かべつち)

wall + dirt = wall clay, wall mud

潮 (しお) Tide

赤 (あか) + 潮 (しお) = 赤潮 (あかしお)

red + tide = red tide上げ (あげ) + 潮 (しお) = 上げ潮 (あげしお)

raise + tide = incoming tide出 (で) + 潮 (しお) = 出潮 (でしお)

exit + tide = high tide

血 (けつ) Blood

生 (なま) + 血 (ち) = 生血 (なまち)

unprocessed + blood = new blood生き (いき) + 血 (ち) = 生き血 (いきち)

living + blood = lifeblood返り (かえり) + 血 (ち) = 返り血 (かえりち)

return + blood = spurt of blood

下 (した) Below

年 (とし) + 下 (した) = 年下 (としした)

year + below = younger靴 (くつ) + 下 (した) = 靴下 (くつした)

shoes + below = socksズボン + 下 (した) = ズボン下 (ズボンした)

pants + below = long underwear

Rendaku-Lovers

In contrast to the suffixes above that refuse to rendaku, there are some words that love to rendaku! And while no word always rendakus 100% of the time, scholars have attempted to make lists of words that almost always do.

Here are five of the most common, so-called "rendaku-lovers" for you:

花 (はな)

風呂 (ふろ)

骨 (ほね)

笛 (ふえ)

箱 (はこ)

Just remember that none of these rendaku all the time. There are many other rules and exceptions that affect rendaku. (And you've learned them!) If you see a list of words that rendaku "every single time," be wary and take them with a big ol' grain of salt.

Common Mistakes and Exceptions

Even without all these rules in their heads, Japanese speakers are able to intuitively rendaku or not-rendaku in the right places—kind of like how you naturally know that it's…

The three beautiful little pink pigs.

…and not…

The pink beautiful little three pigs

There are elements of our own languages (in this case, adjective order) that we internalize and know instinctively after a while. It's essentially a built-in, statistical framework that we fill with data over years and years, so we just know when something feels right.

There are, however, some words that are tricky even for native Japanese speakers. For example, 生牡蠣 is the Japanese word for "raw oyster," and it's supposed to rendaku:

生 (なま) + 牡蠣 (かき) = 生牡蠣 (なまがき)

raw + oyster = raw oyster

But it isn't uncommon to see 生かき written on a menu, and you're still supposed to know to read it as 生がき, although some people obviously read it as 生かき by mistake.

The same thing happens with the word 寿司 (すし) for "sushi." 寿司 is a word that almost always rendakus, but it's written in hiragana on menus because it has a more elegant, refined look. For example, 鯖寿司, mackerel sushi, does rendaku:

鯖 (さば) + 寿司 (すし) = 鯖寿司 (さばずし)

mackerel + sushi = mackerel sushi

But on menus it will be written as 鯖すし, and some folks will also read it as さばすし, when it should still be さばずし. Keep an eye on your menus, and make sure you rendaku your order correctly!

For words that aren't used very often, it's easy to forget about rendaku, especially when they're words you only see in kanji. Here are some common words that even Japanese people can get mixed up:

名 (めい) + 台詞 (せりふ) = 名台詞 (めいぜりふ)

famous + line = famous line/quote木綿 (もめん) + 豆腐 (とうふ) = 木綿豆腐 (もめんどうふ)

cotton + tofu = firm tofu鷹 (たか) + 匠 (しょう) = 鷹匠 (たかじょう)

hawk + artisan = falconer酒 (さけ) + 造り (つくり) = 酒造り (さけづくり)

sake + making = sake brewing作 (さく) + 付け (つけ) = 作付け (さくづけ)

harvest + making = planting

Even without all these rules in their heads, Japanese speakers are able to intuitively rendaku or not-rendaku in the right places.

Finally, one common issue is that sometimes one word can rendaku to mean one thing, but doesn't rendaku when it's used to mean something else. This is rare, but one example is 瓦葺き: when referring to the act of "roofing and tiling a roof," it should read かわらふき, with no rendaku. But when it refers to "a tiled roof," it should read かわらぶき, with rendaku. Can you figure out why? The first one is dvandva, an equal relationship that blocks rendaku. This isn't a common word, so it's easy to mess up, no matter who you are.

Even TV reporters can have a hard time understanding how to rendaku words. In his past blog post, MBS newscaster Tamaru Kazuo (田丸一男) explains that he's confused about the word 悪口, which means "verbal abuse," "bad-mouthing," or "slander." He reads it as わるぐち, because (according to the rules) it should rendaku, yet dictionaries list the primary reading to be わるくち. But other reporters read it without the rendaku.

While 悪口 can technically be read either way, different people have different opinions of what sounds right and what doesn't. In this way, language is always changing, and words that once didn't rendaku become words that do over time, just because it feels like they should.

Here are some other words that historically did not rendaku. But because people tend to read them that way (mistakenly or not), you'll hear them rendaku nowadays anyway.

芋 (いも) + 焼酎 (しょうちゅう) = 芋焼酎 (いもじょうちゅう)

potato + shōchū = sweet potato shōchū (a type of distilled liquor)奥 (おく) + 深い (ふかい) = 奥深い (おくぶかい)

interior + deep = profound, deep返り (かえり) + 咲く (さく) = 返り咲く (かえりざく)

return + bloom = to come back, to bloom a second time河川 (かせん) + 敷 (しき) = 河川敷 (かせんじき)

rivers + spread out = flood plain過 (か) + 払い (はらい) = 過払い (かばらい)

excess + pay = overpaying未 (み) + 払い (はらい) = 未払い (みばらい)

not yet + pay = unpaid, overdue過 (か) + 不足 (ふそく) = 過不足 (かぶそく)

excess + deficiency = excess and deficiency (dvandva should block this rendaku!)凍え (こごえ) + 死ぬ (しぬ) = 凍え死ぬ (こごえじぬ)

freeze + die = freeze to death税 (ぜい) + 引き (ひき) = 税引き (ぜいびき)

tax + off = tax excluded庭 (にわ) + 作り (つくり) = 庭作り (にわづくり)

garden + making = gardening見え (みえ) + 隠れ (かくれ) = 見え隠れ (みえがくれ)

appear + hide = appearing and disappearing (dvandva should block this rendaku!)紫 (むらさき) + 水晶 (すいしょう) = 紫水晶 (むらさきずいしょう)

purple + quartz = amethyst

In the modern Japanese language, most of these words will appear in dictionaries without rendaku. But as more and more people say and write them with rendaku, that will change.

Practice Your Rendaku!

If you made it this far, congratulations! You now know more about rendaku than your Japanese professors (probably). Even better, you have the tools to understand rendaku when you see it, even with all of those pesky exceptions out there.

If you want more rendaku, we took the initiative and made a whopping 350 word list of words that do and do not rendaku. Use your fancy new rendaku knowledge to master them all!