In the US, feeding yourself while traveling is pretty much just a chore. Highway rest areas with the same fast food chains all over the country let your fuel yourself and your car at the same time, but you wouldn’t call it a treat. You won’t starve on Amtrak, but you’re better off packing a lunch, and if you take the bus that may be your only option. And airline food – ugh, better not to think about that at all.

When you travel by train in Japan, it’s a different story. Ekiben 駅弁, the bento sold on trains and in train stations, were once a simple necessity for hungry travelers. Modernized in the face of competition from the private auto, now they serve as souvenirs and promotion for local tourism. Now people even flock to buy them when they’re not traveling – for sure something that would never happen with an airline meal.

Come with us on a journey from the first simple rice ball to a wonderland of local delicacies, charming presentations, and delicious, delicious Japanese food.

The First Japanese Train Station Bento Box

It’s clear that train travel started in Japan in 1872, but the beginning of the ekiben is a little harder to pin down. There are various competing theories as to what counts as the first ekiben, as is often the case with an idea whose time has so obviously come. There were trains, there were people, people get hungry. The market was so ready that it almost had to happen in some form, and surely more than one merchant met the need. But who would think to keep precise accounts of who first sold a thing that hadn’t even been defined yet? What’s more, many historical records were lost in the war, so even if they did, they’re long gone now.

The standard narrative gives the honor of being first to a meal that was sold at Utsunomiya station in Tochigi prefecture, consisting of two rice balls in a bamboo wrapper, with pickles. It sold for five sen. One sen is 1/100 of a yen, so that was the equivalent of around 10 dollars in current money, which is about the price of a nice ekiben today.

Competing possibilities for the honor of the first are actually earlier, including meals sold in Osaka and Kobe in 1877 and Ueno Station in 1883, among others. I wonder if the Utsunomiya station one wins more or less official recognition because apparently we know the exact date it was first sold – July 16, 1885, the opening day of the Japan Railway Tohoku main line. That gives us a precise anniversary to celebrate. Pretty convenient.

Something this good needs more than one excuse for a party, though, and ekiben are also celebrated on another day: April 10 is Ekiben 駅弁 no の Hi 日, because the Japanese cannot resist a kanji pun. Apparently 弁 looks like a combination of 十 (ten) and the Arabic number 4? Whatever. Any excuse to eat more ekiben, right? This year, April 10 was in fact celebrated as the 130th year of the ekiben by the association for Japan Rail ekiben makers as you can see from this official flyer.

The Ekiben Develops

The ekiben quickly began to take on the features that are recognizable today. 1888 saw the first standard ekiben with rice and a bunch of side dishes, sold at Himeji Station. Some sources say the first ekiben to feature local specialties were sushi ekiben sold at Ichinoseki and Kurosawajiri in Iwate beginning in 1890, but whoever started it, the idea took off in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. While travellers didn’t have websites to consult in those days, by 1905 a magazine listed the different ekiben available in different places, and some railway timetables would list the famous ekiben of the region.

In the old days, ekiben vendors carried their wares on a display tray that hung from a strap around their necks. Announcing themselves with a special sales call, they walked along the platform and sold through the windows of the stopped trains.

This charming custom died out when trains became climate-controlled, with windows that didn’t open, as well as schedules that were tighter. Sales have mostly moved to kiosks and to inside the train, but there are still a few places left with old-fashioned platform vendors (here you can see photos from some train stations that still had them in the early to mid 2000s).

Along with local specialties, ekiben incorporate a couple of other features essential to traditional Japanese cuisine. Some feature seasonal foods and are only available at certain times, and always, beautiful presentation is vital. Even when made in large facilities instead of by local cooks, attention is still paid to the presentation and placement of each item. (For example, check out this report of a visit to an ekiben factory.)

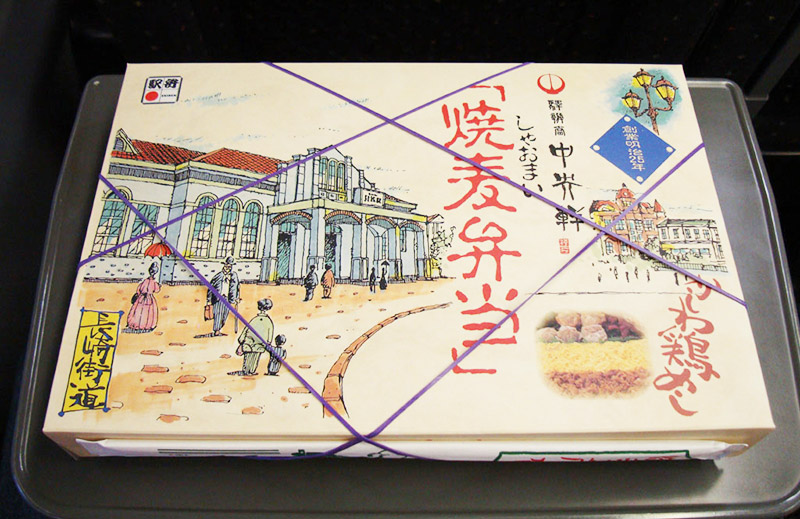

When we talk about presentation, that includes the box and wrapping as well as the food itself. These are not your supermarket/conbini bento in plastic trays. Not to knock conbini bento, which are one of my favorite things, but one way ekiben compete with these cheaper options is with souvenir containers and attractive packaging. Fun containers include the shinkansen above, and my favorite, this octopus jar:

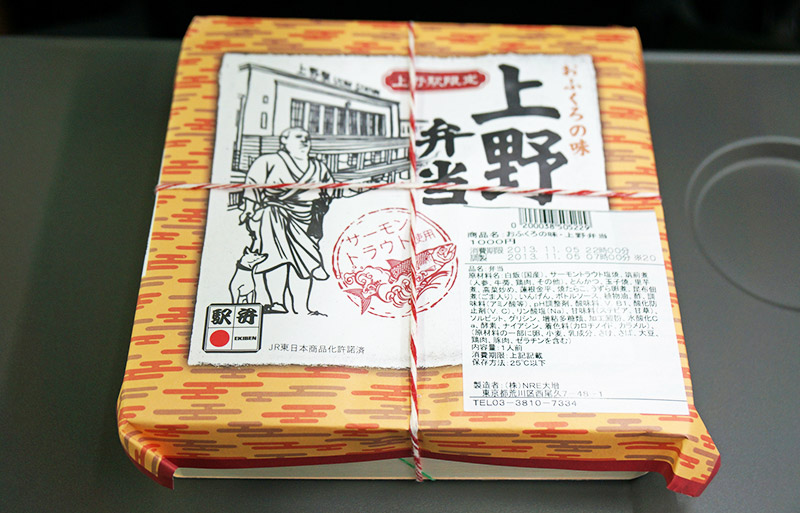

Ekiben in more conventional boxes are covered in wrappers that feature a fantastic variety of Japanese art and graphic design. Many give you an idea of the food inside, with elegant drawings of fish or produce. Others commemorate occasions – for example, there was a special ekiben at Tokyo Station for the 1964 Olympics. And some include historical or folkloric figures and famous sites. This one from Ueno Station features the station facade and the statue in Ueno Park depicting Saigō Takamori, often called the last samurai, and his faithful dog:

Pop culture characters get into it too. For the full experience of that sort of thing, watch someone buy an Anpanman ekiben and eat it on an Anpanman-themed train:

And then you can spend hours on this site navigating one guy’s collection of over 6000 ekiben wrappers, some going back to the 1900s, and some, if he bought the actual meal himself, with photos of the contents as well.

The Ekiben Rises, Falls, and Rises Again

During World War Two, ekiben were affected by rationing, with limited rice supplemented by sweet potato or noodles and fancy wrappers replaced by plain paper, sometimes with patriotic slogans. One famous Japanese dish came out of this period. Ikameshi, squid stuffed with rice, was invented by an ekiben vendor in Hokkaido using small squid that weren’t otherwise being made use of. Stuffing the squid with the rice and simmering the result made a small amount of rice into a more satisfying meal.

After the war in the 1950s, there was a travel boom, and with the rise in popularity of TV, interest in ekiben was spurred by a 1973 drama based on a manga about a guy who travels around Japan to try them. These decades were the golden age of ekiben. Consumption rose from about two million boxes per week in the late 1970s to twelve million boxes daily in the mid 1980s.

Times changed though as private car ownership became more common and flying became more popular as a way to travel. Ekiben purchases dropped, and 1987-2008 saw a 50% decline in the number of ekiben makers. To save their companies, new ideas were needed. Some of these were technological, like self-heating boxes, but even more attention seems to have been given to promotion. Maybe the most brilliant realization was that if people weren’t taking the train as much, what we needed was ekiben minus the eki. The first department store ekiben festival took place in 1966, and in two weeks sold 400,000 ekiben of 200 different kinds from all over the country. Now, instead of the train taking you to sample local specialties, the local specialties came to you, at least for a couple weeks out of the year.

Ekiben Today

While some say ekiben have seen better days, they really don’t seem to be doing all that badly. They are keeping up with the times with anime-themed products to catch the attention of young people for whom ekiben don’t have the nostalgia value, like a Naruto ekiben, offered in the home prefecture of the original manga’s creator. Or this one (that I really want) with both nostalgia and kid appeal, a souvenir Kitaro ekiben.

Since that first department store ekiben festival, more stores started holding them, and I’ve even been to an ekiben matsuri at a Mitsuwa market in the US. You can still go to the biggest and most famous annual ekiben matsuri at Keio Department Store in Shinjuku where over 200 varieties are sold. There are cooking demonstrations and special theme events, such as a recent Abandoned Railway Line Ekiben Project that recreated the ekiben of train lines that have been shut down.

But those department store festivals only last a couple of weeks. What if you’re in Japan at the wrong time? Never fear! Now you can head for the new, permanent ekiben matsuri street in the renovated Tokyo Station, where you can choose from 170 different ekiben from all over the country. The three most popular are reportedly a self-heating grilled beef tongue bento from Sendai, a chirashi bento with lots of egg omelet from Niigata, and a beef on rice bento from Yonezawa, Yamagata Prefecture, which is famous for its beef. That’s a lot of culinary geography you can cover without even getting on the train.

But try to do it the old school way at least once. There’s nothing more quintessentially Japanese than eating your ekiben while looking out the window of a train. You may weep at the memory next time you’re served an airline meal, but it’s worth it.