Confession: I am an emoji hipster. Before your mom was sending you grinning emoji or that cute boy was texting you heart-eyes emoji, my study abroad friends and I were using our 2009-era SoftBank phones to send each other long, complicated rows of emoji, most of which involved the poop emoji. (As one does.)

But emoji aren’t just for anyone with a smartphone these days. Moby Dick has been translated into emoji. The March 2015 issue of Wired featured emoji on the cover. Coca-Cola has put emoji in their URLs as part of an advertising campaign. Emoji are even being presented in court cases as evidence. Earlier this year, a man was charged with running an online black-market. During the trial, his lawyer argued that the emoji in his client’s text messages were legitimate pieces of evidence. The judge agreed.

Obviously, emoji have arrived and people like me get to be dreadful snoots about it. Though emoji have come from Japan visually intact, the cultural meanings behind them have been lost or given new, Western meanings. So before I begin writing this entire article using emoji alone (don’t tempt me), let’s look back to find patient zero. Let’s see if we can shine a spotlight on the sorta secret history of emoji. (And explain why Drake’s “praying hands/high-five” emoji tattoo doesn’t mean what he thinks it means.)

Pre-Emoji Emoji

I’m going to go out on a limb here and assume you’re familiar with kaomoji 顔文字, which literally means “face letters.” (Like how emoji or 絵文字 can be translated as “picture letters.”)

Kaomoji and the West’s emoticons primarily sprung out of a need to more clearly communicate emotional intent on early web forums and message boards. As any denizen of the internet knows, a winky face can mean the difference between a sarcastic quip and a straight-faced insult.

Emoticons first hit the scene on Sept. 19, 1982 thanks to Scott E. Fahlman, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University. He suggested using :-) as a “joke marker” after someone posted a fake mercury spill message and other message board users mistakenly thought it was serious. The rest is, as they say, history. ;)

The origin of kaomoji is much murkier, though the general consensus seems to be that the first kaomoji (^_^) appeared a few years later in 1986 on a Japanese forum. Unlike emoticons, kaomoji can be seen as an extension of Japan’s kawaii or cute culture, and are heavily influenced by manga and anime, focusing more on the eyes than the mouth and incorporating things like apostrophized sweat drops and slash-marked blushing.

(Psst – And if you want to bone up on your kaomoji and impress or irritate your friends, Tofugu has a disturbingly comprehensive kaomoji guide!)

Made in Japan

Although Japan’s big cellphone companies, like Docomo and SoftBank, are currently facing some stiff competition from Apple and other Western companies, back in the ’90s, business was booming and Japan was at the forefront of cellphone technology. Internet access and large color screens were already standard features long before Apple got into the mobile phone game. As cellphone usage exploded in Japan, kaomoji naturally made the jump, too. Just like on message boards in days of old, kaomoji were used to garnish conversation and make emotional intent more obvious and clear. This is, of course, is especially important in a language like Japanese, where so much meaning is gleaned from context rather than exactly what’s being said.

In 1998, Shigetaka Kurita was part of the Docomo team working on i-mode. i-mode would become Japan’s most widespread mobile Internet platform and push the nation’s cell phone tech ahead of the rest of the world. Docomo had previously introduced the idea of emoji – sort of.

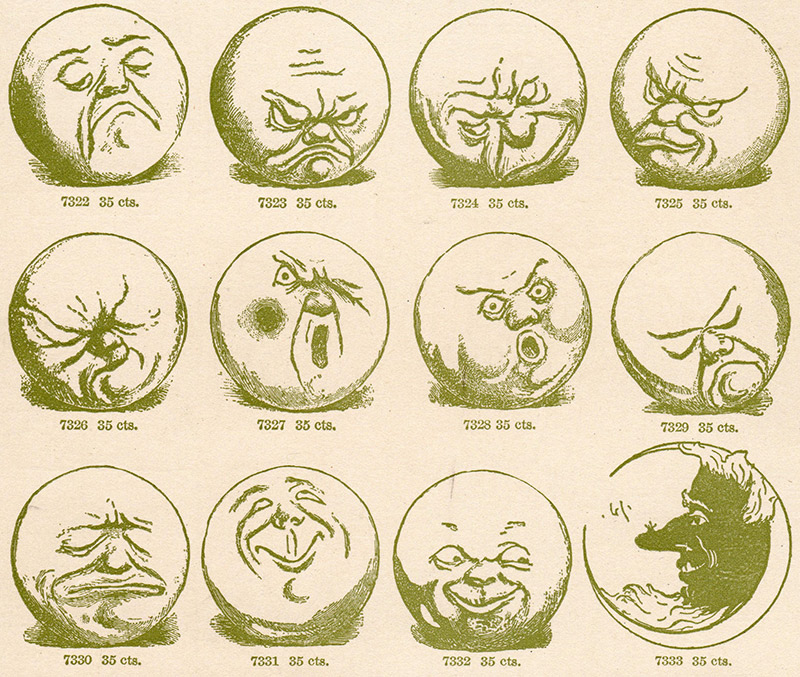

In the mid-90s, Docomo had added a heart symbol to its pagers. The favorable reaction from high school-aged customers didn’t go unnoticed. Sure, people could text each other kaomoji with their cellphones. But Kurita figured there had to be a simpler, more straightforward way to express emotion via text message.

Not being a designer (yet being told to design the emoji anyway), Kurita looked to manga for inspiration. Manga artists use sweat drops, waterfalls of tears, and heart eyes to make their characters’ emotions larger than life. Kurita used these same cues when creating the first set of emoji (176 12×12-pixel characters). Kurita thought Docomo’s various cellphone manufacturers might polish up his emoji designs. Instead they ended up using his work as-is, which Kurita admits isn’t the most sveltely designed. But it didn’t matter. Emoji took off.

Gaining a Foothold

There was just one problem (for Docomo, at least). They couldn’t copyright Kurita’s emoji set, because each emoji was such a small amount of pixels. Competitors like J-Phone (which later became SoftBank) took the concept of emoji and ran with it, adding more and more emoji to their products. But Docomo emojis only worked on Docomo phones and J-Phone emojis only worked on J-Phone… phones. If a Docomo user tried to send a smiling cat emoji to a J-Phone user, that user would only see a hot mess.

Still, emoji were incredibly popular, unseating their more complex kaomoji cousins. It didn’t take long for emoji to start sneaking into other text spaces, like MySpace and AOL Instant Messenger (remember those?). As Apple turned to the Japanese market, they wisely gave the people what they wanted with their iOS 2.2 update in 2008: emoji.

The Journey West

Japanese iPhone users finally had their emoji. But if you were anywhere else in the world or weren’t sure how to mess around with your iPhone settings, no emoji for you. Still, the floodgates had already opened and there was no going back. Especially once emoji were incorporated into the Unicode Consortium in 2010.

Unicode is an international encoding standard for displaying characters on phones and computers. It’s basically the Esperanto of computing languages and scripts. By bringing emoji into the fold, Docomo and J-Phone users could start exchanging emoji. Even better, once emoji were added to Unicode, Apple introduced emoji as a standard international keyboard option a year later, giving emoji its true international debut.

There’s only one person who wasn’t a fan: Scott Fahlman, the guy who invented emoticons. He stands by his opinion that emoji are ugly and undermine using one’s own creativity to express themselves online. (Personally, I think he’s just jealous there’s no poop emoticon.)

Decoding Emoji

Even though emoji’s code has been universalized, so that they can be unleashed indiscriminately across platforms, the meaning behind each emoji doesn’t always make the jump as successfully. Because the emoji we all know and love were intended for a Japanese audience, things can get a little lost in translation.

There are a ton of Japanese food emoji, like:

-

🍡 Dango

-

🍱 Bento

Their meanings are fairly obvious, but some are a tad subtler.

- 🙆 Like the girl holding her hands above her head? Typically, it’s used to denote excitement or awe (or ballet, I suppose). But in Japan, making a circle with your arms means “OK” or “correct.”

Then there are the emoji whose slightly more scandalous meanings have been lost entirely.

-

👯 Those dancing girls in black leotards that are usually used as a shorthand for “best friends” are actually Japan’s version of Playboy bunnies.

-

🏩 I nearly choked the first time someone sent me the love hotel emoji. They must have thought it was just another emoji for hospital or “get well soon.”

Where we don’t see meaning, we inevitably make our own.

-

💁 The girl holding her palm up can mean, “how may I help you?” in one culture. In another it’s a sassy hair flip.

-

🙏 Two palms pressed together can mean a prayer to the Almighty or begging someone’s forgiveness. (Though an argument could be made that those two interpretations are oddly similar.) Some even see it as a high-five.

Emoji’s original purpose may have been to clear up miscommunication. But culture is its own language and it’s not always a universal one.

Making Faces

Emoji clearly aren’t going away any time soon. More have been recently added to the iPhone catalogue, mostly to give users more racial options when it comes to their “girl getting haircut” and “old lady” emoji. But in the same way that message board users in Japan adapted the West’s emoticons into more culturally relevant (and let’s face it, way cuter) kaomoji, Western smartphone users have taken emoji and grafted on their own cultural meanings.

Shigetaka Kurita probably never imagined or intended emoji to be used in a mosaic-style New Yorker cover. Or for the word “emoji” to enter the Oxford Dictionary. Or for Twitter users to reimagine famous works of art as lines of emoji. But people are always going to bring their own culture and creativity to the table, making emoji more than the sum of their pixels. And that’s pretty 👍.