You know what’s more embarrassing than falling on your butt in front of everyone in Japan? Not knowing how to say butt in the first place.

You know what’s more anxiety-inducing than giving a speech in Japanese? Telling the person next to you that you have butterflies in your stomach and then realizing that their horrified reaction means that they took you literally.

One of the first things you learn as a kid is what to call all the parts of your own body—yet for some reason this often gets neglected when you’re learning another language.

Now’s the time to fix that! Especially since Japanese sometimes conceives of the human body a bit differently than English. As a bonus feature, not only can knowledge of anatomy help you complain about the various parts of your body, it can also unlock the door to all sorts of cool idioms to spice up your Japanese – as well as help you avoid awkwardly translating English idioms into Japanese nonsense.

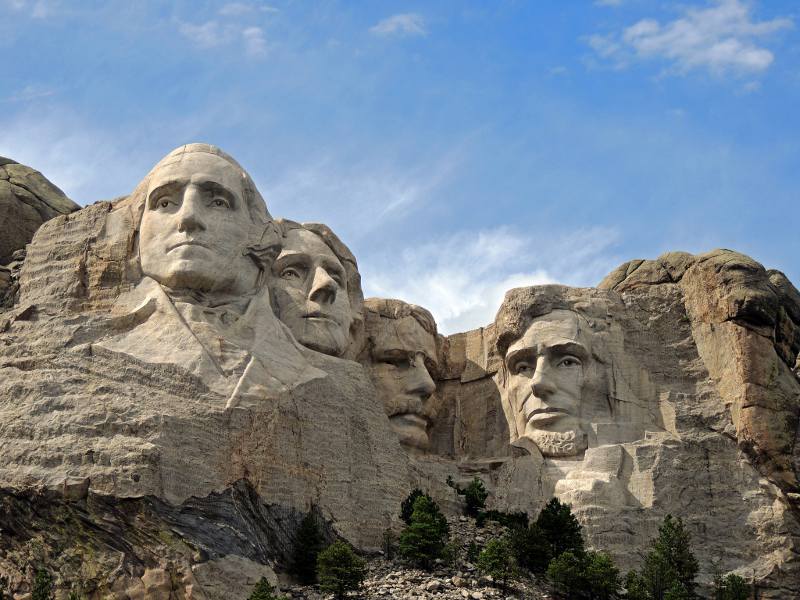

Starting from the head and finishing at the toes, here’s your guide to Japanese anatomy and some of the key idioms associated with its various parts.

頭(あたま)

The big container for your brain, otherwise known as your head. あたま can also refer to a more metaphorical head – the top of something, like a department head or the top of a peak – and it can double as a synonym for the mind, brain, and intellect. You probably already know how to call someone (or yourself) smart by saying 頭がいい(あたまがいい)literally, “head is good.” But there’s more where that came from. Other adjectives you can attach to 頭 include:

- 頭が高い(あたまがたかい): to be haughty (lit. to have a tall head)

- 頭が固い(あたまがかたい): to be stubborn; obstinate (lit. to have a hard head)

- 頭が弱い(あたまがよわい)/頭が悪い(あたまがわるい)/頭が鈍い (あたまがにぶい):three variations on “dumb” (lit. to have a “weak head,” “bad head,” and “dull head”)

- 頭の回転が遅い (あたまのかいてんがおそい): to be slow on the uptake (lit. to have a head that rotates slowly)

- 頭の回転が速い(あたまのかいてんがはやい): to be quick on the uptake (lit. to have a head that rotates quickly)

And here are things that can be done to heads with verbs:

- 頭を使う(あたまをつかう): to use one’s head (lit. to use one’s head)

- 頭を捻る(あたまをひねる): to be puzzled over or think deeply about (lit. to twist one’s head)

- 頭を刈る(あたまをかる): to cut one’s hair (lit. to mow one’s head)

And let’s not forget:

- 頭ごなし(あたまごなし)without giving someone a chance to explain (lit. without one’s head)

- 頭にくる(あたまにくる)to get angry/pissed (lit. to come to one’s head) 頭に置く(あたまにおく)to take into consideration (lit. to put/place in one’s head)

髪(かみ)

It’s hair—those variously colored strands that burst out of your scalp. Be careful though, because 髪 only refers to the hair on your head, and has two super common homonyms –“gods” 神 and “paper” 紙.

Unlike English where you can idiomatically let your hair down when you’re ready to pahhtayyyy, this word is really straightforward and only means what it means. When you cut your hair, you literally cut your hair (髪を切る) and when you fix your hair you literally fix it (髪を直す;かみをなおす). When your hair is long you say it’s long (髪が長い;かみがながい) and when it’s short you say it’s short (髪が短い;かみがみじかい).

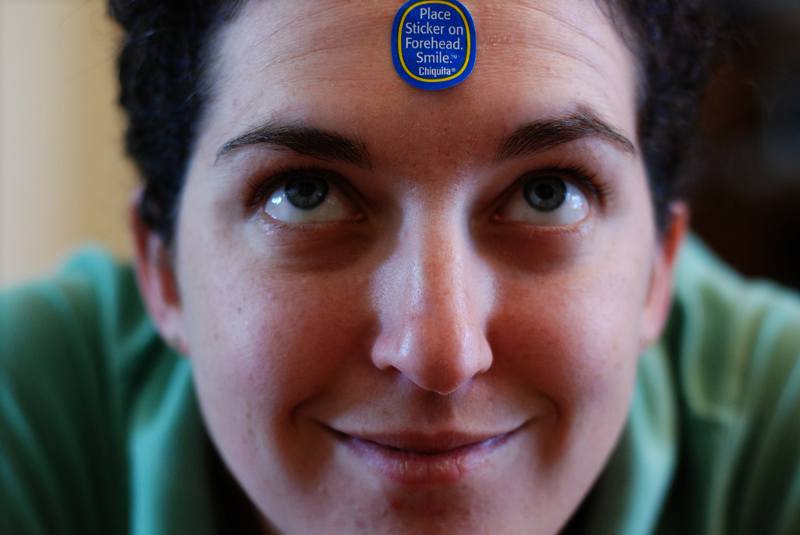

額(ひたい)

You probably don’t often chat with people about your forehead. So why is this worth knowing? Because the Japanese do, when they want to remark on how teensy tiny something or somewhere is—it’s “as narrow as a cat’s forehead” or “narrow like a cat’s forehead.” (猫の額のように狭い or 猫の額ほどの狭い)

顔(かお)

The side of the head with all the holes in it, otherwise known as the face. Sure enough, it’s the go-to noun when you want to discuss your physical face, but it’s also strongly associated with conceptual “face” or reputation and that’s where the fun begins. For example:

- 顔が立つ(かおがたつ)to maintain one’s status or keep face (lit. to have one’s face stand)

- 顔がつぶれる(かおがつぶれる)to lose status or lose face (lit. to have one’s face destroyed)

- 顔に泥を塗る(かおにどろをぬる)to put to shame (lit. to plaster mud on someone’s face)

- 顔が利く(かおがきく)to be influential (lit. to have an effectual face)

- 顔が広い(かおがひろい)to be widely known; to know many people (lit. to have a wide face)

- 顔を出す(かおをだす)to put in an appearance (lit. to show one’s face)

- 顔から火が出る(かおからひがでる)to be extremely embarrassed (lit. a fire appears from one’s face)

耳(みみ)

Here we have the ears, tunnels to your eardrums. Not surprisingly, みみ is frequently conflated with hearing, just as you can “lend an ear” in English when you’re listening to someone. Coincidentally, Japanese also has the same phrase—耳を貸す(みみをかす; lit. to lend an ear. And when you want to exclaim “That’s news to me!” you can say hatsu mimi (初耳; lit. first time ear). A few other handy phrases include:

- 耳を傾ける(みみをかたむける): to listen closely (lit. to tilt one’s ear)

- 耳が痛い(みみがいたい): to hear something bad about oneself (lit. one’s ears hurt)

- 耳に逆らう(みみにさからう): to be hard to take (lit. to go against one’s ear)

- 耳にする(みみにする): to catch wind of; to hear by chance (lit. to come to one’s ear)

- 耳に胼胝ができる(みみにたこができる): to talk someone’s ear off (lit. to create calluses on one’s ears)

目(め)

Next we have the eyes. Similarly to the ears, め often acts as a physical shorthand for sight and vision. But because so much of our life experience is mediated through what we see, 目 has also come to refer to experiences more generally, to particular viewpoints, and to the looks or glances we trade with other humans. Eye level can indicate hierarchical status, too—that’s why 目上の人(めうえのひと;lit. “a person above the eye”) refers to someone’s superior or senior, and 目下の人(めしたのひと; lit. “a person below the eye”)refers to someone’s inferior or subordinate. Other eyeball-filled idioms include:

- 目が回るほど忙しい(めがまわるほどいそがしい)to be as busy as a bee (lit. so busy that one’s eyes spin)

- 目がない(めがない)to have a weakness for something (lit. to have no eyes)

- 目が止まる(めがとまる)to have one’s eye caught on something (lit. to stop one’s eyes)

- 目が高い(めがたかい)to have an expert eye, a discerning eye (lit. to have tall eyes)

- 目に残る(めにのこる)to be engraved in one’s memory (lit. to remain in one’s eyes)

- 目に浮かぶ(めにうかぶ)to come to one’s mind (lit. to rise to one’s eyes)

- 目の正月(めのしょうがつ)a feast for the eyes (lit. a New Year’s for the eyes)

- 目の毒(めのどく)an eye sore OR a temptation (lit. eye poison)

- 目を奪う(めをうばう)to be dazzled (lit. to seize one’s eyes)

- 目を通す(めをとおす)to look over something (lit. to pass one’s eyes over something)

- 目を引く(めをひく)to catch one’s eye (lit. to pull one’s eyes)

鼻(はな)

The nose knows. As you’ve probably guessed by now, 鼻 (like the other sensory organs) doubles as a synonym for the sense itself—in this case, smell. So when someone takes of their shoes and the scent punches you in face, you can say that the scent 鼻に付く(はなにつく;lit. “sticks to your nose”). It’s also used more whimsically as a marker of pride, in phrases like:

- 鼻が高い(はながたかい)to be proud (lit. to have a tall/high nose)

- 鼻毛を読む(はなげをよむ)to make a fool of someone (lit. to read someone’s nose hairs)

- 鼻であしらう(はなであしらう)to snub someone; to turn up one’s nose (lit. to handle with the nose)

- 鼻で笑う(はなでわらう)to laugh scornfully (lit. to laugh with the nose)

But let’s not forget that the time we’re most likely to be concerned about our nose is when it’s not behaving well. That is, when you’ve got a runny nose — 鼻水が出る(はなみずがでる; lit. “nose water comes out”)– so you grab a tissue — 鼻紙(はながみ; lit. “nose paper”)– and end up giving yourself a nose bleed–鼻血(はなぢ; lit. “nose blood”).

頬(ほほ or ほう)

Your cheeks are there for you, man. They’re there when you smile wide (頬笑み;ほおえみ;lit. “cheek smile”) and when you blush (頬を染める;ほほをそめる;lit. “to dye the cheeks”). They even come to your rescue when you’re dying of boredom in class and resort to 頬杖をつく(ほおづえをつ) resting your face in your hands (lit. “to use one’s cheeks as a cane”).

口(くち)

The hole in your face that food goes into and words come out of, otherwise known as the mouth. As such, くち is strongly associated with speaking, but also appears in conjunction with eating, and can be used as a metaphor for holes and openings of all kinds. When it comes to talking we have:

- 口が重い (くちがおもい)to be taciturn (lit. to have a heavy mouth)

- 口が軽い(くちがかるい)to be talkative; to talk without thinking (lit. to have a light mouth)

- 口裏を合わせる(くちうらをあわせる)to make sure your stories agree (lit. to match the backs of your mouths)

- 口から先に生まれた(くちからさきにうまれた)to be a natural born talker (lit. to be born from a mouth)

- 口車に乗せる(くちぐるまにのせる)to cajole someone (lit. to take someone for a ride on a mouth vehicle)

- 口が悪い(くちがわるい)to have a sharp tongue (lit. to have a bad mouth)

In terms of dining, we’ve got:

- 口に合う(くちにあう)to suit one’s taste (lit. to match one’s mouth)

And as an example of “openings” in general:

- 口を探す(くちをさがす)to look for an opening, in terms of work (lit. to look for a mouth)

舌(した)

It’s the most powerful muscle in your body—your tongue. Like the mouth, the tongue takes on some aspects of speaking and eating. Someone who trips over their words or gets tongue-tied easily is said to be 舌足らず(したらず;lit. “lacking a tongue”). Conversely, someone who speaks fluidly and without hesitation is someone who 舌が回る(したがまわる; lit. “one’s tongue turns”). When it comes to food, the tongue can tell you that something has a nice texture with 舌触りがいい (したざわりがいい; “good tongue feeling”). And it makes an appearance when someone’s smacking their lips or drooling over something—舌鼓を打つ(したづつみをうつ;lit. “striking the tongue-drum”). A few other miscellaneous expressions include:

- 舌打ち(したうち)to cluck one’s tongue (lit. tongue-strike)

- 舌を出す(したをだす)to stick out your tongue (lit. to take out one’s tongue)

- 舌を巻く(したをまく)to be astonished (lit. to wind one’s tongue)

歯(は)

And then there’s the teeth–those two rows of food-smashers embedded in your gums. Outside of being brushed and pulled out by dentists, 歯 get to play a rather interesting role in the Japanese language as metaphors for ability and (often unpleasant) social situations. Here’s a taste of what’s out there:

- 歯が立たない for a task to be impossibly difficult (lit. the teeth don’t withstand)

- 歯が浮く to set one’s teeth on edge (lit. the teeth loosen)

顎(あご)

Basically, it’s the bony ledge that defines the bottom of your face, including the chin and jawline. That’s right, it’s two English words for the price of one. 顎 also appears in a few handy phrases like顎で人を使う(あごでつかう, to order somebody around (lit. “to use somebody with your chin.”).

首(くび)

While “neck” is a fine way to conceive of 首 in general, you should be aware that it sometimes more closely corresponds (in English, at least) to everything up from the neck. For example, what we might say is cocking your head to the side would be expressed with 首を傾げる(くびをかしげる; “to tilt the neck”). 首 also stands in as a synonym for being unemployed. On that last point, this largely comes into play with the two complimentary phrases for “to fire someone” or 首にする(くびにする; lit. “to turn into a neck”) and “to be fired” or 首になる(くびになる; “to become a neck”. Other idioms include:

- 首を長くして(くびをながくして)expectantly; eagerly (lit. to lengthen one’s neck)

- 首を捻る(くびをひねる)to rack one’s brain (lit. to twist one’s neck)

- 首を縦に振る(くびをたてにふる)to nod one’s head (lit. to wave one’s neck vertically)

- 首を横に振る(くびをよこにふる)to shake one’s head (lit. to wave tone’s neck horizontally)

- 首を突っ込む(くびをつっこむ)to meddle in (lit. to thrust one’s neck)

肩(かた)

Here we have the shoulders, or the sloping line from your neck to your upper arms. Given the tendency 肩 have of getting stiff from stress, it’s probably not surprising that they appear as metaphors for responsibility (much like “shouldering a burden” in English). Their role in defining physical posture also plays into how they’re used in Japanese to express position and stance. In that vein, similar to the English “standing shoulder to shoulder,” Japanese uses 肩を並べる(かたをならべる). Among these types of idioms are:

- 肩に担ぐ(かたにかつぐ)to bear a burden (lit. to carry on one’s shoulders)

- 肩が軽くなる(かたがかるくなる)to be relieved of one’s burden (lit. one’s shoulders are lightened)

- 肩を持つ to support someone; to stand by someone (lit. to hold someone’s shoulders)

- 肩代わり taking over a responsibility (lit. changing shoulders)

- 肩で風を切る to swagger about (lit. to cut the wind with one’s shoulders)

- 肩身が狭い to feel ashamed (lit. to have narrow shoulders)

- 肩身が広い to feel proud (lit. to have wide shoulders)

腕(うで)

At the ends of the shoulders we find the arms. 腕 can do a lot of crap. Take a simple tree, for example. With arms, you can climb that tree, chop down that tree, turn that tree into fire, and then plant another one. All of these tasks that arms can accomplish manifest in Japanese with the usage of 腕 as a synonym for skill and ability. See for yourself:

- 腕を試す(うでをためす)to put one’s abilities to the test (lit. to try one’s arm)

- 腕を磨く(うでをみがく)to hone one’s skills (lit. to polish one’s arm)

- 腕が鈍る(うでがにぶる)to become less capable (lit. for one’s arm to become dull)

- 腕を振るう(うでをふるう)to display one’s ability (lit. to brandish one’s arm)

And then when the day’s work is done, you can:

- 腕を枕にして(うでをまくらにして)to use one’s arms as a pillow (lit. to turn one’s arm into a pillow!)

手(て)

The hands, that remarkably dexterous collection of hundreds of bones at the end of your arms. Even more so than arms, hands are directly involved with the majority of things we humans do, and as such they can idiomatically represent the many things that hands do—work, help, care for, hold, write. In a similar vein, 手 can stand in for a means or a way more generally, hands being a means to accomplish lots of things. Here’s a sample to get your hands dirty:

- 手が空いている(てがあいている)to have free time (lit. one’s hands are empty)

- 手が足らない(てがたらない)to be short of hands (lit. to not have enough hands)

- 手に入る(てにはいる)to come into one’s possession (lit. to enter one’s hands)

- 手を引く(てをひく)to back out of something (lit. to pull out one’s hands)

- 手を組む(てをくむ)to join forces (lit. to link hands)

指(ゆび)

The hand would be pretty useless without fingers. It’s also worth learning the names for your individual fingers, if you haven’t yet:

- 親指(おやゆび)thumb (lit. parent finger)

- 人差し指(ひとさしゆび)index finger (person-pointing finger)

- 中指(なかゆび)middle finger (lit. middle finger)

- 薬指(くすりゆび)ring finger (lit. medicine finger; medicine paste used to be applied with this finger)

- 小指(こゆび)pinky finger (lit. smaller finger)

Other than that, there’s only a few idiomatic phrases worth learning. When you’re giving something a try, in English we might say you’re dipping a toe in, but in Japanese it’s dipping a finger in—指を染める(ゆびをそめる; lit. “to dye a finger”). Then there’s a pretty visual phrase for “looking on enviously without doing anything”—(口に)指をくわえる(くちにゆびをくわえる;”to put a finger in one’s mouth”).

胸(むね)

The chest, the pecs, the breast. むね is also the go-to word for a bunch of emotions and sensations that seem to emanate from that area. So you’ll use it when you’re keeled over from heartburn (胸焼け;むねやけ: “chest burn”) and when you’re tense with anxiety (胸ぐるしい;むねぐるしい;lit. “troubled chest”). It also often seems to correspond with “heart” in phrases like “to be open-hearted” or 胸が広い(むねがひろい;lit. “to have a broad chest”). Others include:

- 胸がいっぱい(むねがいいぱい)to be overwhelmed with emotion (lit. for one’s chest to be full)

- 胸が躍る(むねがおどる)to be excited and/or elated (lit. for one’s chest to dance)

- 胸騒ぎがする(むねさわぎがする)to feel uneasy (lit. for there to be noise in one’s chest)

- 胸を焦がす(むねをこがす)to yearn for something or someone (lit. to burn one’s chest)

- 胸を痛める(むねをいためる)to worry oneself (lit. to make one’s chest hurt)

- 胸を打つ(むねをうつ)to be touching (lit. to strike one’s chest)

- 胸に畳む(むねにたたむ)to keep something to oneself (lit. to fold in one’s chest)

腹(はら)

Moving on further south, we land at the stomach—not the organ itself, though! That’s for another day. This is the exterior stomach area, linguistically linked in Japanese with instinctual feelings and with people’s REAL intentions or thoughts. Some examples are:

- 腹が黒い(はらがくろい)to be black-hearted (lit. one’s stomach is black)

- 腹が立つ(はらがたつ)to be angry (lit. one’s stomach stands)

- 腹ができている(はらができている)to be resolute (lit. one’s stomach is prepared)

- 腹の中で笑う(はらのなかでわらう)to laugh/smile to oneself (lit. to laugh/smile in one’s stomach)

- 腹積もり(はらづもり)one’s real intentions (lit. stomach intentions)

- 腹時計(はらどけい)one’s internal clock (lit. stomach clock)

背(せ)or 背中(せなか)

Flipping over to the other side of the body we have the back. This probably appeared in two of the first descriptors you ever learned in Japanese, when you had to describe your ideal romantic partner in stilted sentences at 8AM (or maybe that was just me). So-and-so is tall or 背が高い(せがたかい; lit. “to have a high back”)and so-and-so is short 背が低い(せがひくい; lit. “to have a low back”). In addition to height, 背 appears in a few other worthwhile idioms:

- 背中合わせ(せなかあわせ)to be at odds (lit. to be back to back)

- 背を向ける(せをむける)to pretend not to see (lit. to turn one’s back)

- 背中で教える(せなかでおしえる)to teach by example (lit. to teach with one’s back)

腰(こし)

Connecting the back and the stomach we have the waist/hips/lower back region all wrapped up into one handy word. As a core of bodily support and the point at which the body bends, 腰 gets quite a workout in the following idioms:

- 腰が重い(こしがおもい)to be slow to act or start working (lit. one’s waist is heavy)

- 腰が軽い(こしがかるい)to cheerfully work (lit. one’s waist is light)

- 腰が強い(こしがつよい)to be persevering (lit. one’s waist is strong)

- 腰が弱い(こしがよわい)to lack firmness (lit. one’s waist is weak)

- 腰を入れる(腰を入れる)to take a solid stance (lit. to put one’s waist into it)

- 腰を落ち着ける(こしをおちつける)to settle down (lit. to relax one’s waist)

尻(しり)or お尻(おしり)

You’re probably sitting on one right now—your butt. Just as English has quite a few colorful phrases related to the hindquarters—to get a kick in the butt and to kiss someone’s ass, to name a few—and Japanese doesn’t disappoint, either. Some are remarkably close to English equivalents and others are delightfully vivid and original. Let’s dive in:

- 尻に敷く(しりにしく)to dominate or boss someone around (lit. to cover the butt)

- 尻が軽い(しりがかるい)to be ahem unchaste (lit. to have a light butt)

- 尻が重い(しりがおもい)to be lazy (lit. to have a heavy butt)

- 尻馬に乗る(しりうまにのる)to follow others blindly (lit. to ride a butt horse; aka the last horse in a line)

- 尻切れ(しりきれ)an abrupt ending (lit. the butt cut off)

- 尻が長い(しりがながい)to overstay one’s welcome (lit. to have a long butt)

- 尻押し(しりおし)support; supporter (lit. butt push)

- 尻もちを搗く(しりもちをつく)to fall on one’s bus (lit. to pound butt mochi; to pound one’s butt into mochi)

- 尻の穴が小さい(しりのあながちいさい)to be small-minded (lit. to have a small butt hole)

- 尻に火が付く(しりにひがつく)to be pressed by business (lit. one’s butt catches fire)

- 尻の毛まで抜かれる(しれのけまでぬかれる)to be completely ripped off (lit. to have everything up to the hair on one’s butt pulled out)

足(あし)

It’d be hard to stand without them—your legs. Well, and your feet. They’re a package deal in Japanese. The closest they get to separate entities is when 足元(あしもと)is trotted out for a few phrases including the omnipresent (in Japan, at least) loudspeakers saying 足元にご注意ください(足元にご注意ください;”watch your step!”). Although that really feels like cheating because all 足元 means is “origin of the leg.” Even footsteps translates to 足音(あしおと;lit. “leg sound”). That’s just the way it is, folks. 足 can also double as a synonym for the way in which or the pace at which someone walks as in the pair 足が遅い(あしがおそい)and 足が速い(あしがはやい), meaning to be a slow walker and a fast walker, respectively. Other idioms of interest are:

- 足を洗う(あしをあらう)to turn over a new leaf (lit. to wash one’s feet)

- 足が出る(あしがでる)to go over budget (lit. one’s legs stick out)

- 足任せ(あしまかせ)wandering without a particular destination (lit. leaving it up to one’s legs)

- 足元を見る(あしもとをみる)to size someone up (usually to take advantage of them) (lit. to see someone’s feet)

- 足が地に着かない(あしがちにつかない)to be on top of the world (lit. one’s feet don’t touch the ground)

- 足を取られる(あしをとられる)to be tripped up (lit. to have one’s legs taken)

膝(ひざ)

Then we have the knees, those knobbly little joints in the middle of your legs. A few idioms that hinge on knees are:

- 膝をつく(ひざをつく)to get down on one’s knees (lit. to attach one’s knees)

- 膝を突き合わせる(ひざをつきあわせる)to discuss unreservedly or intimately (lit. to touch knees with one another)

- 膝を進める(ひざをすすめる)to draw closer (lit. one’s knees proceed)

足の指(あしのゆび)or 爪先(つまさき)

Last and possibly least, we have the toes. Because instead of giving them a dedicated word, Japanese just smashes together two other anatomy words when they bother to refer to them at all (足の指;lit. “fingers of the leg”). Alternately, there’s 爪先(つまさき; lit. “tip of the (finger or toe) nails”)which is actually usually translated as tiptoes, not toes. BUT! If you want to scream about how you just stubbed your toe, it’s つま先をぶつける(つまさきをぶつける;lit. “to bump into with tiptoes”). Go figure.

There we have it — Japanese anatomy from head to toe. Of course, some body parts didn’t make the cut (my apologies to elbow and eyelash) but the goal here was to lay a solid foundation by focusing on basic words that either differ from English usage and/or pack a cultural punch. Hopefully the idioms not only give you some insight into Japanese conceptions of the body but also help you remember the names of the body parts themselves. So now if you do indeed fall on your butt in front of everyone in Japan, you can impress the stunned onlookers by exclaiming, 「尻もちを搗いた!」(しりもちをついた; “I fell on my ass!”; lit. “I made butt mochi!”). In fact, I might just start saying that in English.