I often tell newcomers to Japan to assume that there's a giant conspiracy going around. A conspiracy that aims to hide the uglier parts of Japan. While Japan does have its share of problems, it papers over them pretty well. The typical tourist therefore heavily risks mistaking Japan as a wholly prosperous country.

There isn't a conspiracy of course, but skepticism is healthy no? After all, tourists tend to go to the successful tourist spots and forget all of about the unsuccessful ones. How can you know if you haven't seen it? These are largely spread out, decaying in the declining Japanese countryside. A countryside invisible to the typical tourist. After all, visitors tend to cluster in the main cities, and the rural areas that tourists visit are still tourist spots. They tend to be well kept.

Outside of this veneer, the Japan beyond the main cities has started to drift into population decline. As I traveled around Tohoku researching, it was hard to miss. This article wishes to address why the country is emptying and if anything can be done about it.

Population Problems

First, take a look at this interactive map produced by Nikkei News. The map indicates the population growth/loss by percentage in all the municipalities of Japan between 2010 and 2014, sorted by color. The more autumn-like the color, the greater the population loss.

The large swaths of pale green that you see indicate municipalities which have lost 0-10% of their population in the past 4 years, ie. the majority of Japan. Exceptions which show marginal growth are clustered around the main urban areas with few outliers.

This variation of the map will prove more startling. Now you're looking at the expected percentage change in the young (20-39 years old) female population of Japan by 2040.

There are probably around 20 localities in green. The rest of the country is coated in varying shades of bright autumn. The deepest purples indicate a greater than 80% loss in this key population group. Furthermore, zoom out and you will see that no prefecture is expected to have any growth in this population segment. Rural Japan is expected to fare generally worse.

These are dire straits for many localities outside of the main cities. The point is that in addition to national population decline, Japan's countryside is expected to be hit the hardest. Already there is talk of some localities "vanishing" in the future.

However, the very well known lack of babies is only one part of the problem. In general (as in most parts of the world), fertility in rural Japan beats that of urban Japan hands down. If nothing else were happening it would be urban Japan dying out.

But people, especially young people, are moving from rural to urban areas. This is something they've been doing for the past century. The three main causes of this migration are education, the economy, and culture.

Education

Say you are a middle school kid in rural Japan where trains come once every two hours. Or perhaps you don't have the fortune of having a train line pass through your area at all. Your parents worry about your future but in Japan (and in wider East Asia), having a future means having an education. High school alone usually doesn't cut it so it's off to study more – preferably at a university, even better if it's a famous one.

The best universities are all clustered in major cities. And even if you choose one closer to home it'll still be in a major city within the prefecture at least. And that means moving.

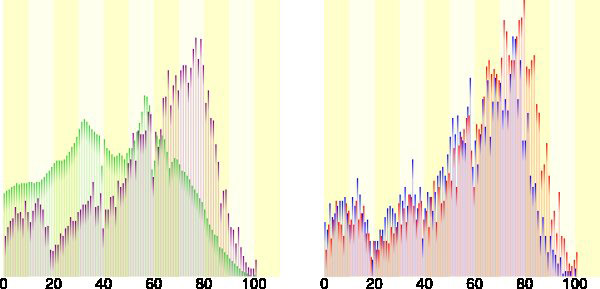

This is why if you look at population graphs of rural towns in Japan there's a very big dip in the population between 18-22 years old. The graph above shows the population graph for Nidogawa-cho, Kochi prefecture (picked at random). Note the very obviously disproportionate elderly population and the very clear valley around age 20 explained by the above.

Naturally, once you move out there's no guarantee that you'll move back. In this way many young people drain out into the main urban areas and stay there.

Here is something curious I found on a visit to Iwaki. Below is a photo of the window advertisements of a cram-school.

The schools listed here are all located in Tokyo. Okay, well Tokyo has many universities anyway so that's not surprising. More importantly, mixed in the congratulations are schools which are not exactly famous; a cram school in Tokyo would probably never advertise some of the listed schools here.

There's lots of ways to interpret it but here's mine: the advertisements are obviously aimed at parents passing by. Therefore some way or another going to a mid-tier Tokyo university (something which is nothing special to Tokyo dwellers) gives your kid enough future prospects for you to fork out money for extra lessons.

Therefore, with higher education being tied to the big cities it's no surprise that Japanese youths are leaving, often permanently.

Employment

Education explains one third of the problem. Another third is work.

Actually, if you look at unemployment statistics, you'll find that the prefecture with the lowest unemployment is actually Shimane whereas Osaka has the third highest unemployment rate in the country. So maybe rural Japan isn't doing so bad after all?

But intuitively speaking, when a rural person can't find work they tend to move to a city for opportunities. When an urban person can't find work, they usually don't think of heading into the countryside. The low unemployment rate of the rural areas may simply be because the young people who would have been unemployed have already moved to the cities in search of work.

Another thing: city-dwellers unambiguously earn more than countryside dwellers. On the other hand, (contrary to expectations) living in rural areas isn't necessarily cheaper. Consider the following:

- You save on rent, but you need a car to get around. This means paying for the fuel and maintenance.

- Food is cheaper, but since other shops are rare there isn't much competition (not to mention having to transport the goods to rural areas). Goods are generally more expensive outside of big cities.

- High fees are necessary to send children away for higher education.

In any case, not all rural areas are doing poorly. However, unlike the major cities which are generally doing okay, there is a spread of winners and losers among the rural areas. And the losers often are marked by:

- Mismanagement: Yubari in Hokkaido (documented beautifully here) is a fine example.

- Sunset industries: Former coal towns (like Yubari) have had their populations decrease since the shutting of their mines. Others have jobs like fishing, agriculture, forestry, etc., which are simply not attractive to younger people.

- An end to pork-and-barrel politics: Japan's government spending has been propping up the rural areas (made clear by this graph). However as Japan has been forced to slim down its public works this support will fall – taking down some localities with it.

Culture

I have to say that in my short trip around Tohoku the youth I saw were pretty much the same as those in the big cities. Guys with lion hair. Girls with very well conditioned hair even though there were no snazzy hair salons in sight. And surprisingly short skirts – so much for inaka conservatism. But then I guess it would be unfair to think otherwise. What else could they be? Unfashionable savages with pock marked faces?

Of course not. But people don't normally grow lion-hair naturally and so this must come from somewhere. That somewhere probably being the national / internet media which certainly pushes city trends.

So imagine that you are a high-schooler. You are inspired somehow, probably through boy bands or Johnny's idols on TV, to make your hair defy gravity. Everyday you take a train which comes once every 30 minutes during the morning "rush hour." Miss that train and you miss one class. On the train ride it's just rice fields or occasionally some shops with 1970s font.

You've probably been to the nearest big city in your region. And unlike where you live there are karaoke chain shops, not dinghy snack bars with a machine that only has enka songs. You are amazed at the lack of shutters in the streets. But above all there's other young people. Aside from school, meeting someone else around your age is a herculean task.

You get the point here. It's no wonder why many young people want to live in the cities. So even if the above two problems were solved, the steady stream of young people into the cities probably wouldn't slow.

What Now?

This is a topic that has garnered a lot of attention in Japan and most people know that something must be done. The central government, and especially the various towns and cities in peril, have put some measures in place. In fact the current government has pushed through a set of reforms under the banner of Chiho Sosei 地方創生 (literally "Creating Life in the Countryside"). Some of the many measures by both central and local governments being taken involve:

- Tax cuts and other incentives for companies to relocate their headquarters out of the main urban areas of Japan.

- Providing people who are considering moving to the countryside the necessary living/job information to do so.

- The central government providing funds to localities who have produced concrete and sound plans for their own revivals.

- Measures to increase the birthrate, including the setting up of sufficient numbers of childcare facilities.

- Active enticing and development of new industries

And we do see some positive examples. Kawakami-mura in Nagano-prefecture has actually seen a population increase from 2005-2010 while Ama-cho has recently gained media attention for its success at attracting young people and its successful economic revival.

The issue is that these are so far the exceptions and no matter how well Japan as a whole handles the issues, there will be some casualties. This is inevitable at the rate at which Japan's population is decreasing (it dropped by around 220,000 people from last year to this year). Therefore, Japan not only has to find out how to revive its declining countryside but manage the decline through perhaps merging unsustainable settlements.

I have to add that this isn't a uniquely Japanese problem. Many countries are also facing gradual declines in rural population. Japan however, is probably the first to experience it on such a scale in a non-wartime scenario.

This means that it doesn't have any examples to learn from, making managing an emptying countryside an extremely difficult task. As metioned before, given the population decline it's no longer a question of if Japan's inaka will empty but to what extent. But, if well managed, perhaps it can be an example for other countries such as neighbours South Korea and China which will follow in its demographic footsteps. Or perhaps even the wider world.