Art is pretty awesome.

One of the most awesome things about art is how it can bring people together. Throughout history, neighbouring peoples have constantly exchanged aesthetic ideas, inspiring the form and content of each others’ work. Art has consistently transcended political conflict, with even the bitterest of rivals sharing innovations.

A prominent and relatively recent example is the modern diffusion of Japanese art across the Western world. While Chinese art has been known in Europe since ancient times, the influence of East Asian aesthetics truly skyrocketed in the nineteenth century, when Japanese prints arrived en masse to shops across Western Europe. As we’ll see, many of the biggest names in the modern art scene received gigantic bites from the Japanese art bug.

Lines of Communication

Direct European contact with Japan dates to the 16th century, with the arrival of Portuguese traders, followed by those of other European nations. Japan was thereby introduced to Christianity, as well as European technologies like ship-building and guns. Naturally, many works of Western art were also imported.

This initial phase of Euro-Japanese relations is known as the Nanban period, where “Nanban” means “southern barbarians”. The term “Nanban art” denotes Japanese art of this period that reflects Western influence, including works of painting, sculpture, and furniture. Yet barbarian influence was quite limited overall, leaving native Japanese aesthetics fully intact.

Meanwhile, works of Japanese art were carried back to Europe. The impact of such works on Western artists was significant, notably in the field of ceramics. But this phase of Japanese influence on the West was a mere trickle compared with the flood to come.

In the early 1600s, Japan’s affair with foreign traders seriously cooled off. The Tokugawa, who ruled the country for upwards of three centuries, were somewhat averse to contact with the outside world; anyone caught trying to leave the country, for instance, could be executed. With policies like this in place, European residents and trade flows, though not eradicated, became increasingly rare.

Then, in the late nineteenth century, America sent a group of friendly visiting-ships into Uraga Harbour. Using some very persuasive arguments, the Americans convinced Japan to re-open relations with the outside world. From this point onward, Japanese culture would radiate throughout the West.

So It Begins

“Modern art”, which dates roughly from the late nineteenth century onward, sought to break away from traditional aesthetics in favour of novel means of expression. In search of fresh ideas, many modern artists looked to native artistic traditions around the world, from Sub-Saharan masks, to Mesoamerican temples, to Oceanic tiki sculptures. Modern networks of transportation and communication accelerated these waves of cultural fusion.

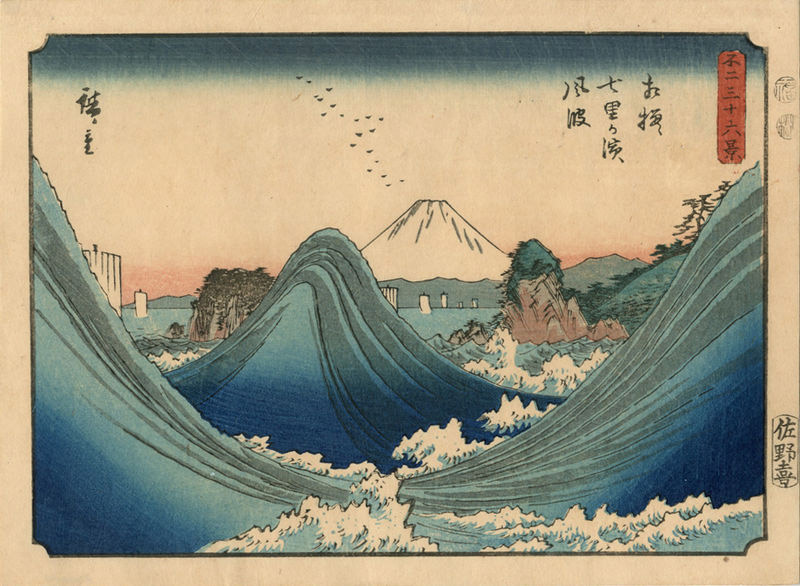

Japanese influence on Western art, often known as “Japonism”, manifested most vigorously in France (followed closely by England and the Netherlands), especially among painters of the impressionist movement. While inspiration was drawn from imported Japanese ceramics, bronzes, textiles, and fans, the foremost medium of influence was the woodblock print. Japanese prints, also known as ukiyo-e, had the advantage of cheap mass-production, making them universally accessible both at home and abroad.

So what form did this influence take, specifically? To start with, European artists often lifted distinctly Japanese imagery from ukiyo-e, grafting them into their own works. Cherry blossoms, lanterns, kimonos, and temples would be four primary examples.

More deeply, ukiyo-e helped reshape the techniques and guiding principles of Western art. The long-entrenched standard of realistic shading and perspective was finally overturned, partly due to Japanese prints. After all, while physical realism is a fine way of doing things, why should it be the only way? The upheavals of modern art were driven largely by the notion that art is about communicating ideas, and that in order to communicate a full range of ideas, one must be open to a full range of forms of expression.

Ukiyo-e typically feature prominent outlines (rooted in the Japanese reverence for calligraphy), and areas of flat, vibrant colour. Shadows are generally omitted altogether. Early modern artists realized that, far from hindering Japanese art, these unrealistic techniques could unlock unique aesthetic experiences.

Woodblock printing was also influential in terms of composition; that is, the overall arrangement of a picture. Traditionally, Western artists laid out scenes carefully to achieve certain effects; Renaissance painters typically sought a balanced, harmonious arrangement, while Baroque painters often went for a sense of unrest and movement. Japanese artists took a more subtle, organic approach, opting for asymmetry, often with the principal figure or object positioned off-centre. Many ukiyo-e scenes are presented from a diagonal view, and figures are often partially “cut off” at the edge of the picture.

Traditionally, Western art was dominated by standard “appropriate” subjects, which generally meant either biblical or classical; while some artists did portray scenes of everyday life, these were widely considered inferior. Part of the great revolution of modern art was the elevation of everyday life to first-class artistic consideration. Modern artists grew fond of capturing urban life, including streets, parks, restaurants, and entertainment venues. This everyday focus was partly fueled by (guess who?) ukiyo-e, in which these very subjects had long been explored.

Had enough background info yet? It’s time to roll out some concrete examples. And why don’t we look at ukiyo-e artists and modern Western painters side-by-side, to really bring out the influences and whatnot?

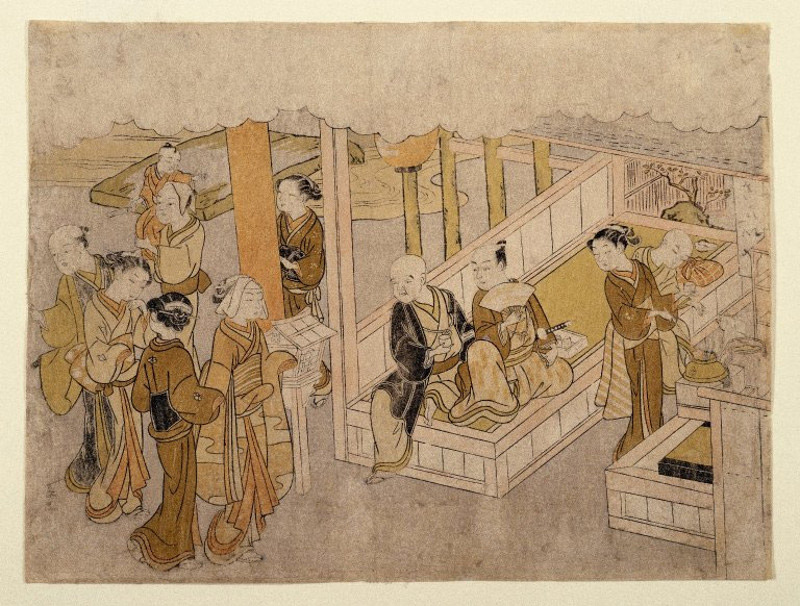

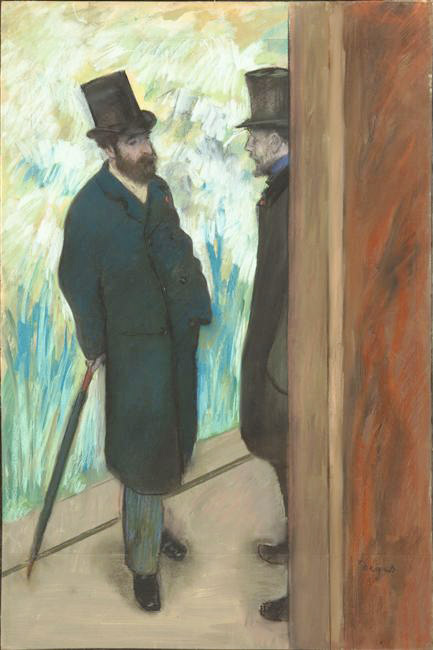

Suzuki Harunobu / Edgar Degas

Suzuki Harunobu is known as the founder of polychrome ukiyo-e. French artist Edgar Degas is considered one of the great founders of the impressionist movement. Both men are known for their many portrayals of women, whether at home, socializing, or as professional performers.

This Harunobu print depicts a young couple at home; the man kneels, reading a scroll, while the woman stands at the doorway. In terms of ukiyo-e influence on early modern art, the most striking feature of this print is its composition. Note the abundance of diagonal lines, along with the sense we are looking down on the scene from a height. The overall arrangement is asymmetrical, with elements positioned in a plausibly natural manner.

This relatively simple painting illustrates Degas’ love of ukiyo-e style composition. The view is elevated and diagonal to the architecture, providing interesting diagonal lines. The scene is sharply asymmetrical, with the right-hand figure cut off by a wall, similar to the partially hidden woman in Harunobu’s print.

Impressionist painters, who seek to capture the overall impression of a momentary scene, don’t concern themselves with sharp, detailed realism. Some parts of impressionist paintings border on abstraction, such as the background behind the two gentlemen in Degas’ painting. Note that a similarly abstract background is found in the top left of the Harunobu print, behind the house.

Kitagawa Utamaro / Mary Cassatt

Mary Cassatt, arguably the greatest American impressionist painter, is known particularly for her portrayals of women, including mothers with children. Ukiyo-e artist Kitagawa Utamoro, whose work Cassatt collected, is known for these same subjects.

Here we have a typical, everyday mother-child scene. Well okay, maybe not completely typical. The child is Kintarō, a popular Japanese folk hero with super strength, while the woman is Yama-uba, Kintarō’s “mountain witch” mother (biological or adoptive, depending on which version of the story you hear).

But still, it’s basically a mother-child scene. Note the warm psychological connection between the pair, as well as the close-up view (such that most of Yama-uba’s body is cut off) and the off-centre positioning.

This Cassatt painting depicts a sensitive mother-child scene in typical sketchy impressionist style. Just like Kintarō and Yama-uba, the figures exchange an affectionate gaze; the child’s hands rest on her mother’s embracing arms, just as Kintarō’s left hand grasps his mother’s wrist. Like Yama-uba, this mother leans at a diagonal, only back instead of forward.

Utagawa Hiroshige / Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Hiroshige, known particularly for scenes of nature, was a master of capturing weather and the seasons. His work became a major influence for landscape painters of the impressionist movement.

This print, which features a prominent figure over a landscape background, is from a series Hiroshige created while travelling along the Tōkaidō, the principal Japanese road of the age. Once again, diagonal lines are abundant, drawing the eye in criss-cross fashion across the picture. The mountain and tree are both cut off at the edges, and the colouring is mostly flat and contained within prominent outlines.

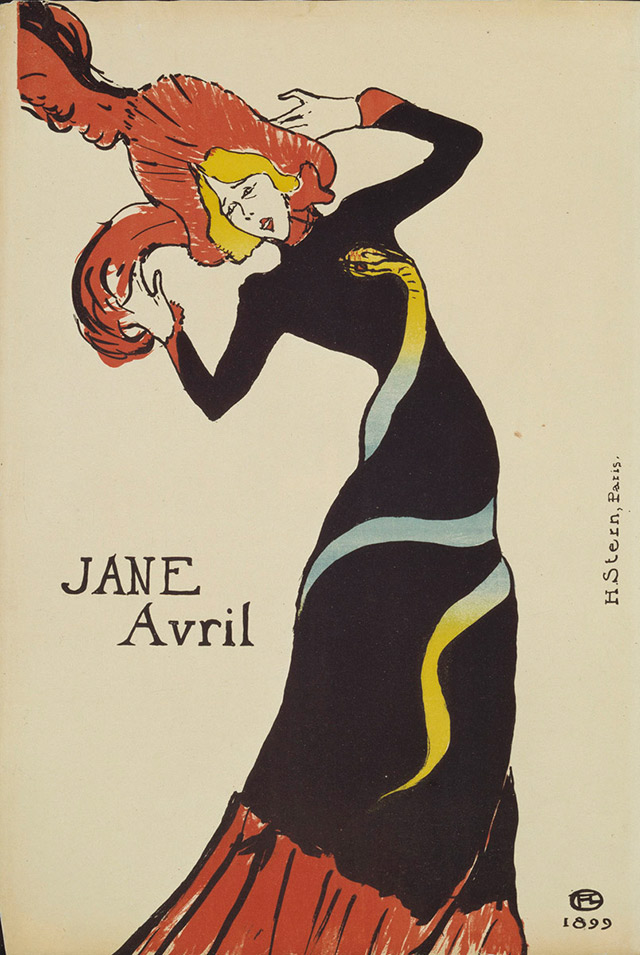

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, painter and printmaker, is perhaps the most iconic ambassador of the bohemian artist lifestyle. His depictions of Paris night life and theatre drew partly from ukiyo-e, which often feature equivalent scenes of Japanese recreation, including kabuki theatre. Toulouse-Lautrec eagerly embraced the vivid colouring and dramatic curved forms of Japanese prints.

In addition to the age-old art of painting, modern technology allowed a new medium to flourish: the poster. Toulouse-Lautrec is considered one of the leading figures in the “golden age” of poster advertising, which spanned the late nineteenth century. The actress in this Toulouse-Lautrec theatre advertisement, executed in bold outlines and flat colours, features a sinuous, diagonal posture that echoes the Hiroshige print above.

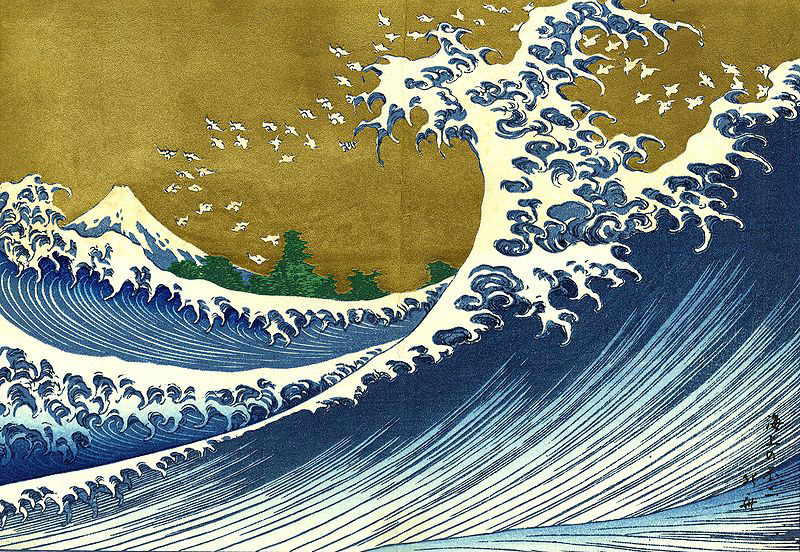

Katsushika Hokusai / Vincent Van Gogh

Hokusai is probably the most famous of ukiyo-e artists, due to his most famous work: The Great Wave, from a series of prints focusing on Mount Fuji. Along with landscapes and seascapes, Hokusai is known for his closeup studies of plants and animals. Landscapes were also among the favoured subjects of Van Gogh, the troubled Dutch artist, for whom ukiyo-e provided immense inspiration.

This print undulates with a gentle asymmetry, in the form of clustered houses and rolling hills. As usual, colours are few in number and flat in texture, with some parts of the scene left strategically uncoloured. Hills are evoked with simple outlines, rounded out with lateral sub-lines and vegetation.

Like Hokusai’s print, this Van Gogh painting features a rolling asymmetry of hills and vegetation, executed in a simple, bright colour scheme. The angled rows of haystacks lend the scene a vigorous bottom-left to top-right momentum. Outlines are thick, and there is little in the way of shading or shadows.

A Universal Language

Art of the late nineteenth century laid the foundation of modern art, which continues to this day. Even as the early twentieth century was ravaged by war, artistic endeavour pierced the darkness with lights of cooperation and understanding between kindred spirits across the world. Ukiyo-e was, and continues to be, very much one of those lights.

Art really is pretty awesome.