In 1543 the first Europeans arrived in Japan. Two (maybe three) Portuguese merchants aboard a Chinese ship were blown off course and forced to land on the island of Tanegashima, just south of Kyushu. Only six years later, the first Christian missionary came to Japan. What followed was, what some historians call, Japan’s “Christian century.” Despite 100 years of Christian dominance, today only about 1% of the Japanese population is Christian. In this article we’ll look at what happened in between. There will be a focus on Kyushu because many of the significant events of Japan’s Christian history were centered there. Those first Portuguese men to arrive at Tanegashima also brought the first guns to Japan. Today’s article will focus on the sixteenth century, during which time guns and Christianity were often entwined. Both had a heavy impact on Kyushu and Japan at large during this period, known as the Warring States period (sengoku jidai), a century where central authority in Japan had lost its sway and samurai clans vied for dominance.

The Apostle of the East

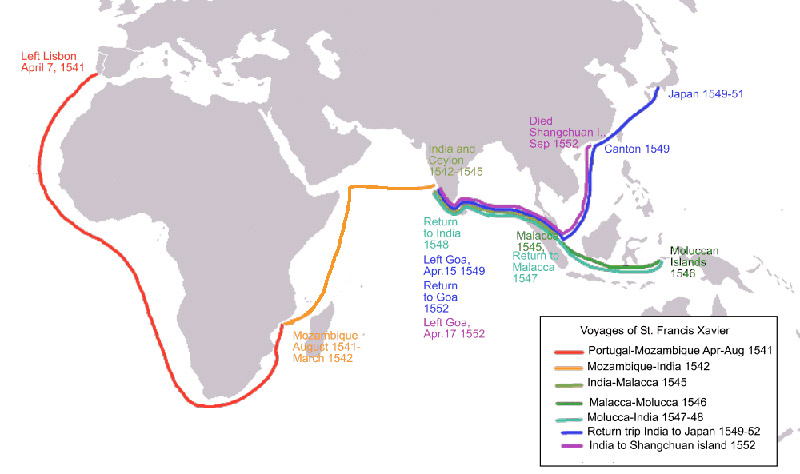

Francis Xavier (1506-1552), the first Christian missionary to Japan, was born to an aristocratic family in Spain. Xavier became a founding member of the Society of Jesus (better known as the Jesuits). They were the first order to specifically make missionary work their purpose. In the early 16th century the Portuguese had established colonies in India, including Goa. In 1541, Xavier sailed to Goa to take charge of the Jesuit mission there. After a few years of preaching to southern Indians and uncouth Portuguese sailors with little success, he moved on to another Portuguese colony, Malacca, Malaysia in 1545. It was at Malacca that Xavier met a young Japanese man named Anjiro (or Yajiro, according to other sources), who was curious about Christianity. Anjiro was from Satsuma (modern day Kagoshima prefecture), on the south end of Kyushu. After being implicated in a murder, Anjiro had fled to Malacca, where he picked up some Portuguese, and developed an interest in Christianity. That interest, combined with Anjiro’s stories of Japan, convinced Xavier that it might be prime territory for spreading the word. The two set sail on a Chinese ship, along with two Spanish Jesuits, an Indian and two more Japanese converts. On August 15, 1549 they disembarked at Kagoshima.

Making Good Impressions

The Shimazu family who ruled Satsuma also controlled Tanegashima, the island where the first Europeans had landed. The Shimazu had been impressed by European firearms and were quick to reproduce them. So, when Xavier arrived they respectfully welcomed him, curious to see what he might have brought along. They gave him permission to speak to their subjects and, through translators, they began to preach. Xavier and his Spanish colleagues began studying Japanese, and soon were attempting the occasional sermon in Japanese, transliterated into the Roman alphabet for them. For the most part, Xavier and European missionaries who followed were quite impressed with the Japanese people. The Jesuits, for their part, were unyielding on matters of faith, but otherwise tried to adapt to local customs. They limited their meat consumption to better fit into Japanese society. They couldn’t be persuaded to bathe daily as the Japanese did, but compromised by doing so once a week (or every fortnight in the winter). Although the Jesuits found many admirable qualities among the locals, there were generally hostile relationships between them and the Buddhist clergy. Though there were a few interfaith friendships, the Jesuits often accused Buddhist monks of being lazy and sodomites. The Buddhists thought the Europeans were spreading lies.

Mission Impossible

Some of the most curious quirks of the Jesuits’ mission in Japan sprang from dealing with the language barrier. Xavier once described Japanese as “the devil’s own tongue.” Xavier and others were largely working through Japanese translators, but they were trying to convey something that had no precedent in Japan. An early mistake was when Anjiro translated God as Dainichi, a Buddhist deity. This led people to think the priests were from some new Buddhist sect, and Xavier didn’t discover the error for two years. They tried Deus (deusu), but decided it sounded to close to daiuso “big lie.” They settled on Tenshu “Lord of Heaven.” The missionaries found many translations carried Buddhist connotations, so they began to use the Latin or Portuguese words for new ideas. For example, they used the word bataren (from the Portuguese, padre) to refer to themselves, so they wouldn’t be confused for Buddhist priests.

Comings and Goings

Ten months after Xavier’s arrival, the Shimazu changed their stance towards the Christians, prohibiting proselytizing and further conversions. This was probably prompted by the landing of a Portuguese ship at Hirado, in northern Kyushu and outside of Shimazu territory, which dashed Shimazu hopes of securing European trade through the missionaries. Xavier left for Hirado, having only converted 100 people in Kagoshima. Xavier made another 100 converts in Hirado, but didn’t stay long, leaving Kyushu and striking out for Kyoto with hopes of meeting the shogun or perhaps the emperor, stopping briefly in Yamaguchi and Sakai along the way. When he reached the capital, Kyoto, he was disappointed by the effects of the civil wars. The shogun was in exile, the emperor powerless and nearly penniless, and the residents too worried about the next attack to care about his message. Xavier headed back the way he came. During his first stop in Yamaguchi, Xavier had made a poor impression on the local lord, Ouchi Yoshitaka (1507-1551), but on the return journey he decided to try again. This time he pulled out all the stops, dressing in a fine silk cassock and bringing gifts, including a clock, wine, textiles, cut glass, a pair of spectacles, a telescope, and a three-barrel musket. The lord was pleased and gave them both permission to preach and an abandoned temple, Daidoji, in which to stay. Xavier spent four months there before going to Bungo, in eastern Kyushu. Xavier had remained the head of the Jesuit mission in Goa, India during his entire adventure in Japan. When a Portuguese ship landed at Bungo, he hoped to receive word from his Indian mission. There was no word to be had, and Xavier felt he must return to Goa aboard the ship to see to his responsibilities. After two and a half years in Japan, sowing the seeds of the Christian mission, Xavier said farewell to the country that he once described as “the only country yet discovered in these regions where there is hope of Christianity permanently taking root.” The following year he died of illness on a small Chinese island.

Convenient Conversions

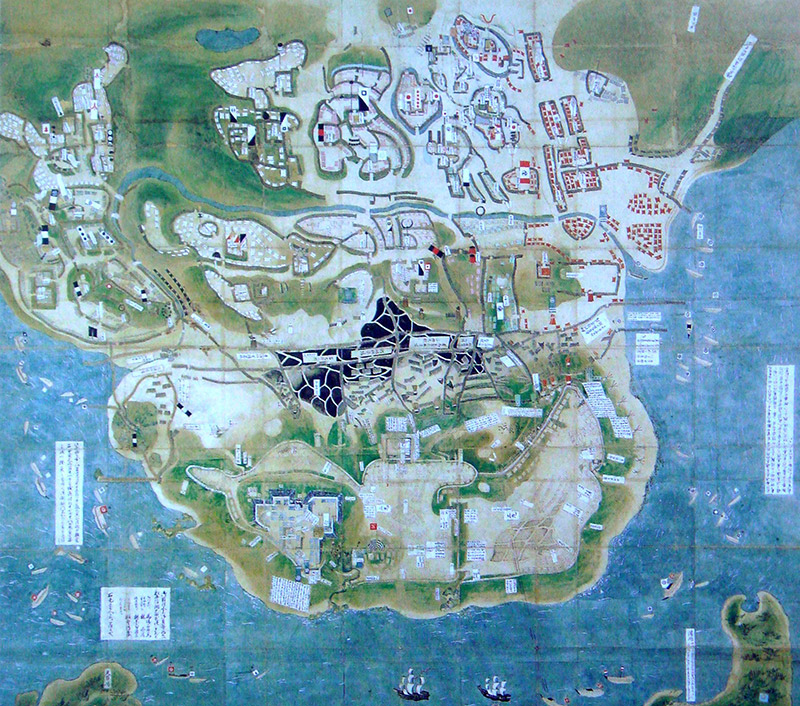

Before Xavier left Bungo for Goa, he was granted an audience with the local lord, Otomo Sorin (1530-1587). Sorin gave the Jesuits a building which became their headquarters. Many years later, Sorin converted to Christianity himself, but this initial generosity was probably a political move to draw in Portuguese trade. Kyushu became the hotspot for lordly conversion. The first lord to convert was Omura Sumitada (1533-1587), with territory in northwestern Kyushu. In 1561, Jesuits approached him, saying that if he would “permit the law of God to be preached in his land, great spiritual and temporal profits would follow him therefrom.” Sumitada gave them the port of Yokose-ura, and converted to Christianity in 1563. Though “temporal profits” seem to have been a factor, Sumitada acted zealously on behalf of his new faith, burning down temples and shrines. His actions provoked a revolt led by a rival family member. Yokose-ura was burned by the rebels, so in 1570 Sumitada opened the port of Nagasaki to the Jesuits. At the time of its opening, Nagasaki was a small fishing village, but from then on it grew into a center of foreign activity.

The Enemy of My Enemy

Around this time, the Jesuits made their most powerful ally, Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582). The first of Japan’s great unifiers began to patronize the Christians in 1568. Doing so helped him in trade with the Portuguese, getting guns and cannons to aid his conquest. Nobunaga appreciated the austerity of the Jesuits, and found hypocrisy in a Buddhist clergy who “preached about suffering while living in luxury.” Nobunaga never converted, and it doesn’t seem that he ever believed in the Christian message, but he certainly had no love for Buddhist institutions either. A number had been thorns in his side. He burned the great temple complex on Mt. Hiei, killing roughly 25,000, and spent eleven years fighting the ikko-ikki, a type of militant Buddhist group. In Nobunaga’s town shadowed by Nobunaga’s castle at Azuchi, the Jesuits set up a school for the children of the local elite, called the Seminario. There they taught Latin, the history of Christianity, music, and Japanese literature. Unfortunately, it lasted only three years, because in 1582 Nobunaga was betrayed by one of his generals, and chose to kill himself rather than be captured. The traitors then attacked Azuchi Castle, which burned down along with the Seminario. Nobunaga had been a source of hope for the Jesuits, and with his death there were even harder times ahead for the Christian mission in Japan.

The next great unifier to take his place was a general of Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598). Hideyoshi had worked his way up from peasanthood to become the most powerful man in Japan. Due to his background, he was never able to take the title of shogun, but he was equally influential. His policies laid the groundwork for what was to come, including an increasing suspicion of Christian motives.

The King of Bungo

Just before leaving Japan in 1551, Francis Xavier met with Otomo Sorin (1530-1587), lord of Bungo (in eastern Kyushu). Initially reluctant to meet with Xavier due to slanderous descriptions given by Buddhist clergy, Sorin was convinced to see him by a Portuguese captain, who described Xavier as a man of high status who could commandeer a European vessel anytime he wished. Sorin gave the Jesuits permission to preach in his territory and a building to use, but it would seem his initial generosity was not religiously motivated. In 1562, he even became a Buddhist lay-priest.

However, over time he may have had a change of heart. In 1578, he converted to Christianity, taking the name Francisco in honor of Xavier. Actually, a marital problem led to his conversion. Sorin had married a woman in 1550, who was staunch in her traditional religious beliefs and shared a contentious relationship with the Jesuits. She is known only as Jezebel, the name the Jesuits used to refer to her. In 1578, Sorin became ill, which the priest Luis Frois claimed was Jezebel’s fault. He was nursed by one of her ladies-in-waiting, with whom he fell in love. Sorin had his new paramour spirited away to a seaside villa where they were free to hear Christian instruction. First, she converted, taking the name Julia. Later Sorin also converted. They soon married, and Jezebel, as a pagan, was no object. To many observers Sorin’s behavior was scandalous, but to the Jesuits he was a hero. Sorin’s happiness did not last long.

At the same time that Sorin was pulling a Henry VIII, there was trouble brewing further south. The Shimazu family, which had rejected Christianity, had begun to expand their territory northward. They soundly defeated the Otomo at the Battle of Mimigawa (1578). The Shimazu were doing so well that by the mid-1580s, nearly all of Kyushu was theirs. Knowing the Shimazu’s final push would come soon, Sorin asked Toyotomi Hideyoshi for aid. In 1587, Hideyoshi’s armies entered Kyushu and began pushing the Shimazu forces back southward to their home territory until they were forced to surrender.

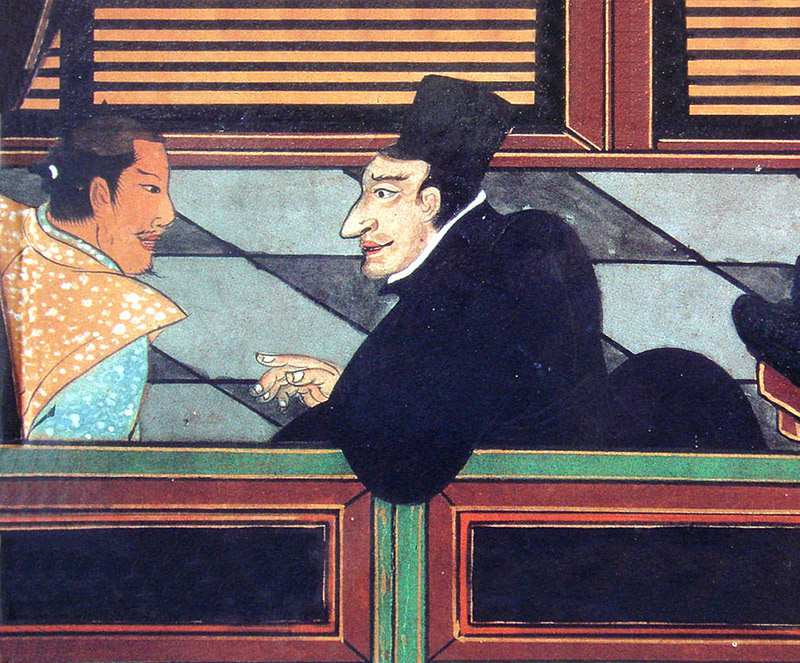

Christian Cruise

Otomo Sorin did one other major thing in the history of Christianity and Japan. In the midst of combating the Shimazu in 1582, he and two other Christian lords sponsored the first official Japanese embassy to Europe. The embassy was the brainchild of Italian Jesuit, Allesandro Valignano (1539-1606), who had been preaching in Japan for three years. The Tensho Embassy (named after the reign-name of the time) consisted of four Japanese converts. With them was their European tutor and translator, and two servants. They stopped at Macau, Kochi, and Goa along the way. Valignano himself accompanied them as far as Goa.

The embassy arrived in Lisbon in 1584, and from there went on to Rome. During their European tour, they met several kings and two successive popes. In Rome, one of the converts was made an honorary citizen. They returned to Japan in 1590, after which Valignano ordained them as the first Japanese Jesuit fathers.

A Tenuous Tolerance

Having conquered Kyushu, Hideyoshi soon finished what Nobunaga had started and united all of Japan under his banner. Like his predecessor, Hideyoshi expressed an interest in what the Europeans had to offer. When the Tensho Embassy returned from Europe, he received them at Osaka Castle, curious to hear their stories and the music of European instruments, like the harpsichord, which they had learned to play. However, under his rule we can also see the seeds of doubt that would ultimately lead to the downfall of the Christian mission in Japan.

In 1587, Hideyoshi issued an edict to expel the missionaries (not all Europeans). He seemed mainly concerned that too many lords were converting, and were also forcing the conversion of their retainers and subjects. There was a worry that Christian lords might have conflicting loyalties. Fortunately for the padres, the edict was not well enforced. They there were able to remain in Japan, they had to keep quiet for a while. This was not true, however, of the Franciscans and other orders, more recently arrived, who continued to preach boldly. This led to Japan’s first martyrs.

The 26 Martyrs

In 1596, the San Felipe, a Spanish galleon shipwrecked off of Shikoku, spilling its cargo of silks and gold. When the local authorities confiscated as much of this as they could and detained the crew, the ship’s pilot warned them to be careful lest they wind up a Spanish colony like South America. He told them “the missionaries come as the king of Spain’s advance guard.”

This was just the wrong thing for Hideyoshi to hear, and from a list of 4,000, ultimately 24 leading Christians from the Kansai area were arrested. Hideyoshi had them marched all the way to Nagasaki to face execution. This was symbolic as Nagasaki had become one of the strongest Christian centers in Japan. Along the 450 mile journey, two more were arrested for giving comfort to the prisoners, including a twelve-year old boy. He was given the chance to recant, but refused. On February 5, 1597, the 26 were crucified on a hilltop in Nagasaki. It may sound like Hideyoshi chose this form of execution to be ironic, which I don’t think is out of the question, but crucifixion had long been a common punishment in Japan.

Tokugawa Transition

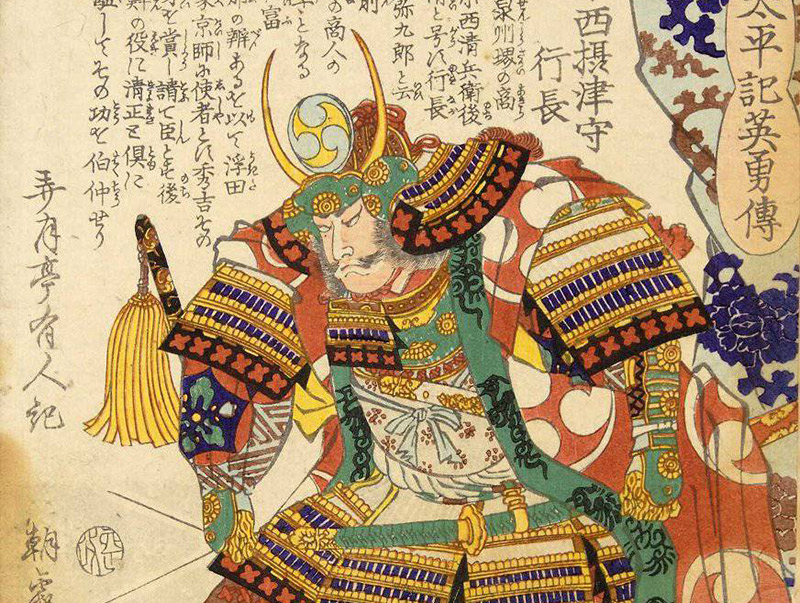

While dealing with issues at home, from 1592-1598 Hideyoshi had thousands of samurai carrying out an invasion of Korea. One of the top two generals of the expedition was a Christian himself, Konishi Yukinaga (1555-1600). Yukinaga often found himself at odds with the other leading general, Kato Kiyomasa (1561-1611), a Nichiren Buddhist. When Hideyoshi passed away in 1598, his war weary generals negotiated an end to the war in Korea, but Yukinaga’s problems were far from over.

Japan soon divided between those supporting the Toyotomi and those supporting another former ally of Oda Nobunaga, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616). In 1600, came the decisive Battle of Sekigahara, and Ieyasu emerged victorious. Konishi Yukinaga had fought for the losing side, but rather than commit ritual suicide (seppuku), he chose execution. This would have been the less honorable choice in the eyes of most of his peers, but his Christian faith taught him that suicide was a sin.

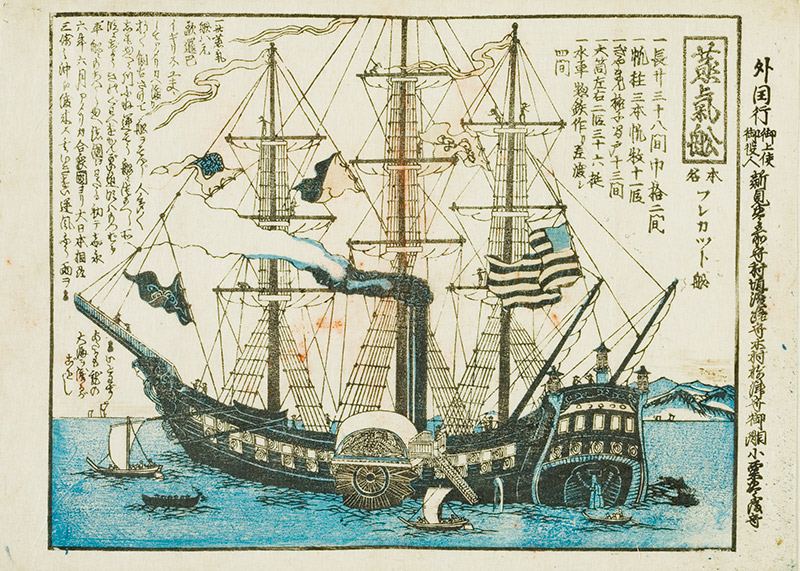

Tokugawa Ieyasu became shogun, and established a line that would rule Japan for the next 268 years. At first, like Hideyoshi, he took a cautious attitude toward Christianity. In 1600, shortly before the Battle of Sekigahara, English pilot William Adams (1564-1620), the basis for the protagonist in James Clavell’s Shogun, arrived in Japan. Ieyasu valued his knowledge, but Adams, out of his own Protestant prejudices against the Catholics, fed the lord’s fears that the missionaries were precursors of a Catholic conquest.

The Hammer Falls

Added to the fear of foreign conquest, one of the biggest concerns that Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu had always had with Christianity was the matter of loyalty. For a Christian samurai, did allegiance to the shogun or the pope take precedence? In 1612 there was a bribery scandal, involving a daimyo and a member of Ieyasu’s council, both Christians. This showed that ties between the faithful might be stronger than those to the central authority. In addition, at the execution of a Christian, a priest told the crowd that obedience to the Church should trump obedience to their daimyo.

These events led Ieyasu to ban Christianity in domains governed directly by the shogunate, and many daimyo followed his example. Then in 1614 he issued the “Statement on the Expulsion of the Bataren”, in which accusations against the priests were leveled. They were commanded to leave the country at once, and Japanese converts were ordered to renounce their faith. Most missionaries left the country, but some continued to operate in secret. Those who were caught were executed.

Anti-Christian measures became even harsher under the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu, who took power in 1623. It’s estimated that in 1612 there were approximately 300,000 Christians in Japan, but by 1625 there were half that or fewer.

Dark Times Ahead

Things were never easy for Christians in Japan during the Sengoku period but, as the country moved toward unification and peace, they came under even closer scrutiny. Though some anti-Christian reasoning points to other issues, it seems that the biggest problem was the fear of those in authority that Christians would have conflicting loyalties. After a century of chaos, betrayals, and civil war, that was something the Shogunate would not tolerate.

The Tokugawa shogunate had begun to persecute Christians, largely out of a fear that Christianity would subvert the order and hierarchy that they had struggled for so long to create and maintain. In 1614, Tokugawa Ieyasu issued a proclamation expelling Catholic missionaries from Japan. Japanese Christians were forced to go underground, becoming known as Hidden Christians (kakure kirishitan). Under successive shoguns, persecution intensified. The final straw was to come in 1637, when a revolt broke out in Kyushu.

We’re Not Gonna Take It!

The Shimabara Peninsula lies on the western part of Kyushu, somewhat out of the way. The lord of the area, Arima Harunobu (1576-1612) was a zealous Christian, and after Hideyoshi’s 1587 expulsion edict, many Jesuits escaped to Harunobu’s domain. He was later involved in the corruption scandal of 1610, stripped of his lands and ordered to commit seppuku. He was replaced by Matsukura Shigemasa.

The life of a Japanese peasant was generally filled with a good deal of suffering. It wasn’t unusual for a lord to treat them poorly. Yet, Matsukura Shigemasa was exceptionally cruel. He taxed everything, even births and deaths, and didn’t take kindly to those who couldn’t pay. Being thrown into a water-filled prison was perhaps the best one could hope for. His most notorious punishment was called the raincoat dance (mino odori), so named because the victim, wearing a straw raincoat, was doused in oil and set on fire, causing them to dance about. Sometimes the family members of those who failed to pay were taken hostage or punished as well. In 1637, when one of Shigemasa’s men assaulted a farmer’s pregnant wife the people finally snapped.

Rebel, Rebel

The violence quickly spread from the original village to others on the Shimabara Peninsula, becoming a serious uprising. The oppressed marched on Shimabara Castle, but couldn’t take it. Meanwhile, the peasants offshore on the Amakusa Islands also revolted. After conferring, they decided to come together at Hara Castle in the south of the peninsula. The vacant castle’s coastal position made it quite the defensible base for the rebels. It was generally illegal for peasants to own weapons, but the rebels still managed to get a hold of some. Still, many had to make do with farm implements, or even sticks and stones (which we all know may break some bones, but are not the first choice for battle).

You may be wondering where Christianity comes into this rebellion. The truth is that it may not have had that much to do with Christianity, at least initially. It had much more to do with the extreme pressure and cruelty that Matsukura Shigemasa inflicted on the peasantry. However, after converging at Hara Castle, the movement acquired some Christian leadership. There were a handful of Christian ronin (masterless samurai), and at the top, a mysterious youth.

This young man was Amakusa Shiro (c. 1621-1638). Born on one of the Amakusa Islands, he was the son of a former Konishi clan retainer (the family’s Christian head, Konishi Yukinaga was killed for picking the wrong side at Sekigahara). He studied with Jesuits in Nagasaki, and according to local lore, made a name for himself preaching equality and dignity for the poor on the island of Oyano. Little else is known about him, but during the rebellion his followers began to think he was the one foretold years earlier by Father Marco Ferraro, a priest who worked in the area before being expelled. He said that, “After 25 years a child of God will appear and save the people.”

The rebels were able to hold out for a surprisingly long time. However, as the winter months wore on, hunger took its toll and the defenses were breached. The victors spent three days slaughtering the rebels. An estimated total of 37,000 were killed, including Amakusa Shiro, and as John Dougill points out, “It’s invidious to play the numbers game when it concerns the dead, but the number killed at Shimabara is almost identical to the 39,000 who died in the Nagasaki atomic bomb.” 10,000 heads were staked up around the castle, and 3,300 were sent to Nagasaki for the same treatment: a clear warning to the people.

Following the Shimabara Rebellion, the Tokugawa took the final step in guarding the country against foreign subversion by expelling all Europeans from Japan and banning their reentry on pain of death. The one exception to this was the tiny island of Dejima, just off Nagasaki’s coast, where an extremely limited number of Dutch ships were allowed to dock and trade.

Methods of “the Man”

In the decades prior to and following the Shimabara Rebellion, the shogunate came up with some strategies for ensuring the loyalty of its subjects and rooting out Hidden Christians. In 1635, the government began to require that all subjects register themselves at a local Buddhist temple, which in 1666 became an annual requirement. Apart from this annual registration, it probably wasn’t necessary to regularly visit the temple. However, groups of households were organized to observe and report on one another, and if one person was exposed as a Christian their family would also suffer the consequences. To avoid suspicion, most Hidden Christians needed to have a Buddhist funeral as well.

Another set of tools at the shogunate’s disposal were fumi-e “stepping-on pictures”. These were small pictures of Jesus or Mary, usually made of metal, stone, or wood. As the name implied, they were designed to be trod upon, a sign that one held no loyalty to the forbidden faith. Fumi-e were first used in Nagasaki in 1628, and became a staple of anti-Christian procedures. The practice even became known to some back in Europe. In Jonathan Swift’s, Gulliver’s Travels (1726), Japan is the only real country visited by the protagonist, who asks the emperor “to excuse my performing the ceremony imposed upon my countrymen of trampling on the crucifix.”

In 1640, a central prosecution office (shumon aratame yaku) was established, with branch offices in each domain. Many Christians were killed, their numbers dropping from 300,000 in 1612 to half that or fewer by 1625. Not only that, but the government knew that if they could make Chirstians publicly recant their faith it would be far more effective than simply creating more martyrs. Thus, various methods of persuasion including horrific tortures were inflicted on many arrested Christians.

Practices of the Persecuted

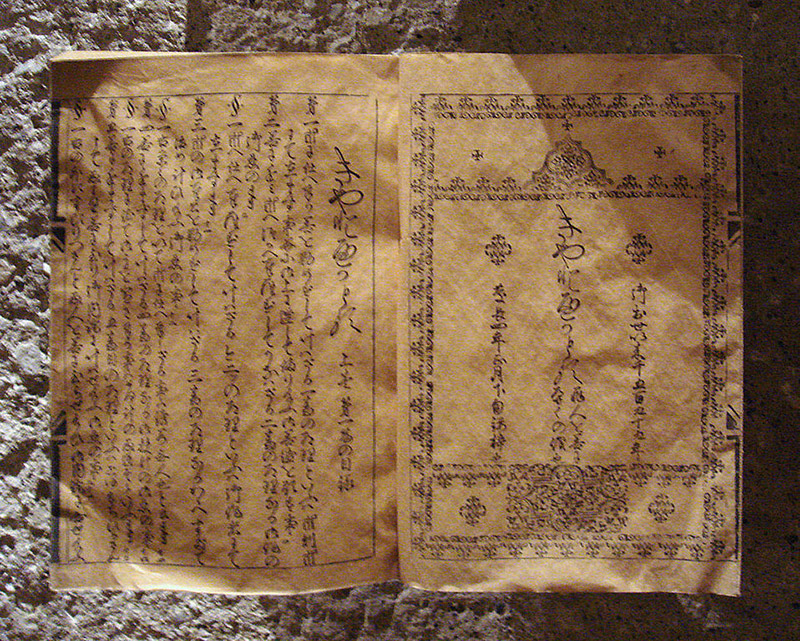

In the face of such persecution, how did Hidden Christians stay hidden? We already saw that there were many misunderstandings in the early days of conveying Christianity to the Japanese people. After the banning of the religion and expulsion of foreigners, the Hidden Christians were left without clergy, leading them to develop some very unorthodox practices.

Without a clergy, the only sacrament left to the Hidden Christians was baptism, as lay people were allowed to perform this in the absence of a priest. Thus baptisms became quite important. They also made statues of the Virgin Mary that look nearly indistinguishable from the Buddhist bodhisattva, Kannon, or Jesus statues disguised as Jizo. In fact, Mary became a major focal point of Hidden Christians’ practice. Though everyone was required to register at a Buddhist temple, in some more rural localities the Buddhist clergy knew there were Hidden Christians, but looked the other way. Still, the consequences of being Christian could be so severe that they learned to be extremely secretive.

Perhaps the most important part of daily practice was the recitation of prayers. Called orashio (after the Latin oratio), these were Catholic prayers such as The Lord’s Prayer and the Hail Mary. They were passed down orally to avoid detection. Those that had been translated into Japanese changed little over the centuries, but not so for those in Latin or Portuguese. For example, “Ave Maria gratia lena” became “Abe Mariya hashiyabena.” In fact, many modern practitioners don’t know what some of their prayers mean. Another important prayer was the Konchirisan (Contrition), which must have assuaged the guilt felt for stepping on fumi-e, holding Buddhist funerals, and all the other compromises Hidden Christians were forced to make in order to keep practicing their faith secretly.

The Second Coming of Japanese Christianity

This state of affairs more or less continued throughout the remainder of Tokugawa rule, with Hidden Christians paying lip service to Buddhism to satisfy the authorities, while practicing Christianity in secret. During the 19th century, even before the reopening of the country to the West, the shogunate began to become lax in enforcing many of the policies they had crafted to carefully maintain the hierarchy of society, including the hunting of Christians. Of course the U.S. finally did force Japan to open up in the 1850s, then the Tokugawa fell in 1867, and the modern Meiji government was established the following year.

Foreign Christians reentered the country, and in 1871 religious freedom became law. Hidden Christians revealed their existence, to the surprise of many at home and abroad. This didn’t mean things became easy. Many Hidden Christians rejoined the Catholic Church. Many chose not to, largely out of respect for the practices of their ancestors, and a feeling that if they abandoned them it would be admitting they were wrong. In addition, as the climate became more and more infused by nationalist State Shinto ideals, being Christian continued to be a liability until the end of World War II.

Considering Japanese Christians have only had about the last 70 years or so to make up for roughly 350 years of persecution, it may not be that surprising that Japan’s Christian population is so small. I won’t dwell on the modern period and reintroduction of Christianity, as the main focus of these articles was meant to be the Hidden Christians. Today there are very few carrying on the Hidden Christian traditions, mostly in Kyushu, particularly on Ikitsuki Island. It’s hard to know exact numbers, but one estimate is that only about 500 practicing members remain on Ikitsuki. Young people today are generally neither interested in carrying on Kirishitan traditions, nor in staying in the rural areas where the religion survived. It seems quite likely that the religion will die out within the next few decades. Even if their beliefs are no longer practiced, the history of the Kakure Kirishitan will remain. Even in three articles, I was only able to highlight some of the major points in Japan’s Christian history. I urge everyone to read more on the subject.