Ah, mother nature. Forests and hills, rivers and oceans, blossoms and bees. Truly, the beauties of the natural world are essential to a happy life.

Of course, mother nature has another, harsher side. Storms, droughts, and floods can be deadly. And the world is full of creatures that bite, claw, sting, and poison.

Many harmful natural phenomena can’t be helped; we must simply deal with them as best we can. But then there are problems we humans bring upon ourselves. Messing around with nature has gotten us into big trouble more than once.

Case in point: Raccoons… in Japan.

But they’re so cute!

It’s true, they are… and as we shall see, that’s how they ended up in Japan. But first, a bit of an introduction.

There are three species of raccoon in the genus Procyon, but the most well-known and numerous is Procyon lotor, also called the common Raccoon or North American raccoon. That’s what’s usually meant when “raccoon” is used on its own, and that’s the one we’ll be talking about here. In Japanese, raccoons are known as araiguma. (Note that the raccoon dog, or tanuki, is a completely different and indigenous creature of Japan.)

Raccoons are a short-legged, omnivorous mammal of medium size, typically in the 10-20 pound range. Native to most of North America, raccoons have rough coats (colored in various mixtures of grey, brown, and/or black), erect ears, and pointy muzzles. Most distinctively, the raccoon has a dark “mask” over its eyes, as well as dark rings around its tail.

In short, a raccoon looks like this:

Pretty darn cute. And the cuteness meter rises even higher when they manipulate things with their dexterous front paws, which feature long, furless “fingers.” The manual dexterity and overall cleverness of the raccoon helps to explain why people might think they would make good pets.

Raccoons become dormant in cold weather, for periods of days or months, depending on how cold it gets in whatever region they happen to live. Their diet is quite diverse, encompassing worms, insects, nuts, berries, amphibians, fish, and birds eggs. Raccoons are equally open to catching live prey or scavenging – with the latter option including human refuse.

And therein lies a major problem (from the human perspective, at least). Raccoons absolutely thrive in human settlements. Agile, (relatively) small, intelligent, bold, willing to dine on pretty much anything edible… and willing to live alongside human beings. (Apparently they aren’t too picky about the company they keep.)

Raccoons tear open garbage and knock over compost bins. They damage buildings and gardens. They carry diseases, including rabies and distemper. They even, on rare occasions, attack people and their pets.

Obviously, none of this is their fault…they’re just being their raccoony selves. But humans often don’t see it that way.

The Invasion

So raccoons are cute, but they can also be troublesome neighbors. That’s just dealing with nature, right? After all, raccoons were around long before human beings.

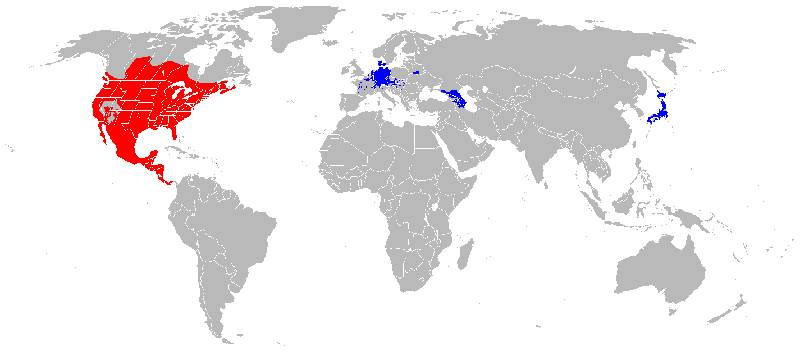

Well, yes… in North America. But elsewhere? Raccoons are indeed found in a few other places, namely Europe (especially Germany), the Caucasus region, and (you guessed it!)… Japan.

The red area on the above map represents the raccoon’s native range. In the blue areas, raccoons are what is known as an “invasive species”. This term denotes an organism that, due to human activity, inhabits a region to which it is not indigenous. “Invasive” also implies that the species has some kind of harmful effect (or at least a major transformative effect) on local ecology; the term “introduced species” is sometimes used to avoid this implication.

Ever since we humans evolved, we’ve been zipping all over the world, with plenty of critters hitching a ride as we go. Sometimes we even bring them along on purpose, as crops, farm animals, or pets. The vast majority of them don’t become invasive. Most species, when introduced to foreign conditions, simply fail to survive in an environment for which they haven’t evolved. A few, however, manage to hang on and consistently reproduce. Some even find themselves at a sudden advantage, often due to lack of natural predators.

An infamous example is the brown rat, originating in China and carried across the world, primarily by seafaring Europeans. The effect was often devastating, notably on bird populations in regions where land predators were hitherto absent, such as remote islands. Indeed, remote islands seem to have experienced the brunt of invasive-species carnage, given their sheer evolutionary isolation.

The most famous victim of species invasion may be Australia, whose vegetation has been ravaged by the introduction of rats and rabbits, while native animals have been gobbled up by wildcats and foxes (the latter having been introduced to control the rabbits). Cane toads, which were introduced to control crop-destroying beetles, ended up slurping down crop-beneficial insects, as well as killing off indigenous predators that are poisoned by their toxic secretions when they eat one. Pretty much every part of the world has its invasive species issues, though. Many native species of fish in the African Great Lakes have been supplanted by introduced fish. The North American Great Lakes struggle with invasive mussels and eels. The storks and small mammals of Florida are being snapped up by released pythons, which are even out-competing alligators for food.

So what about Japan? To start with, mongooses (or “mongeese”, heehee), introduced to control venomous snakes, have been pummelling non-venomous snakes and various wild and agricultural mammals (even goats!). Meanwhile, native fish struggle to dodge the voracious mouths of introduced bass and bluegill. In a 1984 scientific sampling of fish from the moat of the Imperial Palace, 80% of the catch consisted of native species; fifteen years later, a single invasive species (bluegill) had exploded to 90% of the catch. (Someone protect the emperor!)

Japan also has issues with animals originally imported as pets. Through a combination of escape and deliberate release, several foreign species have come to form wild populations. Hedgehogs, red-eared turtles, and ferrets are three prominent examples. Another is the raccoon.

How Did It Happen?

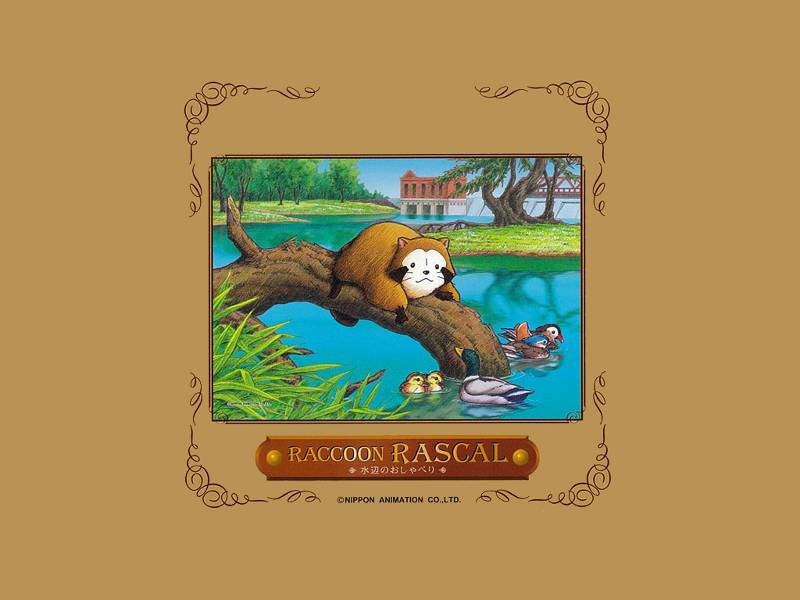

This is one of those rare instances where a major environmental change can be traced back to one individual. And, even rarer, a fictional individual. This is Rascal, star of the 1977 Nippon Animation series Rascal the Raccoon (Araiguma Rasukaru).

The series, set in early twentieth-century rural Wisconsin, follows the adventures of a young boy who rescues a baby raccoon orphaned by a hunter. Rascal, as the boy names his new friend, proves a loving companion. Rascal becomes a crucial source of comfort when, not long after his arrival, the boy loses his mother.

In time, however, Rascal’s position within his human family becomes increasingly strained by his emerging wild animal personality. When Rascal is caught snacking on the crops of neighboring farmers, his outdoor ramblings are suddenly reduced to the confines of a pen. As if that weren’t enough, his unhappiness with domesticated life redoubles when he spots a lady raccoon beyond the walls of his well-intended prison. Ultimately, the boy faces a very difficult, emotional choice…where does Rascal truly belong?

With the massive success of this anime, suddenly everyone wanted a raccoon for a pet. Over the following years, upwards of two thousand raccoons were imported to Japan annually. Apparently algae balls just weren’t cutting it anymore.

Unfortunately, humans don’t have a great track record when it comes to choosing pets. Wild animals that look cute and cuddly aren’t likely to be that way in human hands, or in human homes, and there’s the house-training issue. There might be some exceptional success stories, but for most families, the fantasy of having their very own “Rascal” didn’t work out. Apparently this caught many fans of the anime by surprise, even though Rascal’s unsuitableness as a pet was a central theme.

And that’s how raccoons came to be released into the Japanese wild. It was a pretty sweet deal for the raccoons, too, given that in Japan they lack any significant natural predators. (Their main predators in North America are wolves and coyotes, which don’t exist in Japan, as well as wildcats, which inhabit only a couple of small Japanese islands.) Over the ensuing decades, the raccoon population soared, and Rascal established himself in nearly every part of the country.

What was good for the raccoons was bad for a range of native species, notably birds (whose eggs, as noted earlier, are a staple of the raccoon diet). In human-inhabited areas, raccoons have been scavenging garbage, damaging crops (notably corn and melon fields), and even attacking pets. They’ve also been tearing up buildings, as they scrabble in and out of their adopted homes (typically attics or basements) which the humans so thoughtfully constructed for them.

Which brings us to perhaps the most infamous raccoon issue in Japan: temple damage. It’s estimated that some 80% of Japan’s temple architecture has experienced some kind of damage from these masked bandits.

Architectural wounds are inflicted as the raccoons climb around, leaving gashes in pillars and walls, and punching holes in roofs and ceilings. As they find themselves snug little corners to sleep in, they tear and pry at anything that stands in their way, be it wood, tile, insulation, pipes, or wires. And they naturally leave lots of little raccoon droppings around, which are inappropriate for most buildings, but especially temples.

The most famous victim of raccoon vandalism may be Byōdō-in, a temple in Kyoto Prefecture, and one of Japan’s most famous and celebrated buildings. Given that Byōdō-in has been standing for over 900 years, you can understand why people were alarmed at the appearance of deep claw marks in the ancient wood. Traps were set, and metal fencing was laid over potential points of entry. It’s a painful irony that the success of one iconic Japanese cultural form (anime) should ultimately lead to the harming of another.

What Can Be Done?

How do we handle invasive species? Three basic strategies are:

- Damage mitigation

- Reduction (possibly elimination) of the invasive population

- Prevention of further introduction

The first approach is the most immediate. In Japan, as in other raccoony parts of the world, laborious attempts are made at sealing buildings from entry (particularly in the case of historic properties), while garbage is locked away from those dexterous little hands. Fences can help protect crops. But completely securing fields, buildings, and garbage from thousands of small, clever critters is a truly Herculean (Kintaro-ean?) feat.

In terms of controlling raccoon numbers, local governments across Japan have developed varying policies. Some arrange the killing of thousands of raccoons each year, citing population reduction (or even, incredibly optimistically, eradication) as the goal. Such programs find support among many farmers and urbanites, while taking fire from animal rights advocates.

Naturally, prevention is the best strategy of all against invasive species. Tight regulations on shipping and travelling help to avoid inadvertent arrivals, while pet regulations halt the deliberate import of problematic critters. Not surprisingly, it is now illegal to import raccoons to Japan.

It’s also important to look at the cause of Japan’s raccoon importation specifically: a pet craze. Media-driven pet trends are found across the world, a familiar recent example being spurred by the 101 Dalamatians movie remake (and its sequel), which was followed by a sharp increase in unwanted dalmatian puppies turning up in American dog shelters. Resistance to such crazes, which are patently unfair to the animals involved, must be fostered among the general population of all countries.

Rascal’s Lesson

In the end, we humans are responsible for introducing thousands of Rascal’s cousins to the mountains and cities of Japan. It seems kind of incredible that today, with all our technology, these furry little rascals continue to evade us so effectively. They’ve moved in, and there’s not that much we can do about it.

We need to take this as a learning experience. Think of all the trouble we could avoid, for animals and for us humans, if we can prevent further “species invasions”. If we wise up, Rascal could become a symbol of a great leap forward in human wisdom and responsibility.