Everyone wants to retreat from the world sometimes. But while sitting in your room playing video games, scrolling through Tumblr and reading Tofugu articles may be the only things on your to-do list this weekend, you'll eventually get over that failed test or bad breakup, and leave your room again to rejoin society. (Also, your weakened, sunlight-deprived body will need food that isn't bright orange and puffed.)

But some Japanese people find themselves spending months—sometimes years—of their lives in their bedrooms, only slipping out for midnight treks to the nearest convenience store. Usually male and usually in their twenties, these are Japan's "missing million," otherwise known as hikikomori—and no one really knows why they've withdrawn from the world, though it's not for lack of trying.

A Little Hikikomori History

Saito Tamaki was working as a therapist in the city of Funabashi when he noticed a recurring pattern. Concerned parents kept coming to Saito asking him what they should do about their lethargic and anti-social children, who had sealed themselves inside their bedrooms. Saito would go on to study and later write a 1998 book about these young people called Hikikomori: Adolesence without End.

Two years after Saito's book hit shelves and the topic of hikikomori hit Japanese media, a 17-year-old boy, later identified as hikikomori by newspapers, hijacked a bus and stabbed multiple passengers after revealing his plans on an Internet forum. Another tragedy involving a hikikomori had already occured earlier that same year when police discovered a girl who'd been kidnapped and held prisoner for nearly a decade by a reclusive man who lived with his mother.

Although these were both rare instances of a socially withdrawn Japanese man committing heinous crimes (and to be clear, the majority of people with mental illness are not violent), it pushed hikikomori even further into the forefront of Japan and the rest of the world's awareness. Japan's hidden population of hikikomori wasn't so hidden anymore.

Here's What We Do Know

The lexicographers in the audience may have noticed I'm using the term hikikomori to refer to both the person and the condition. That is, a person who suffers from hikikomori is a hikikomori.In some ways, this reflects how amorphous the subject of hikikomori truly is. Psychologists and other experts disagree on how to classify hikikomori: is it truly a disorder or just a symptom? Is hikikomori uniquely Japanese or does it occur in other countries?

Japan's Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has defined a hikikomori as a person who does not participate in society (particularly school or work) and has no desire to do so. A hikikomori is also someone who doesn't have any close, non-familial relationships. These withdrawal symptoms must last for at least six months and the social withdrawal itself must not be a symptom of a pathological problem.

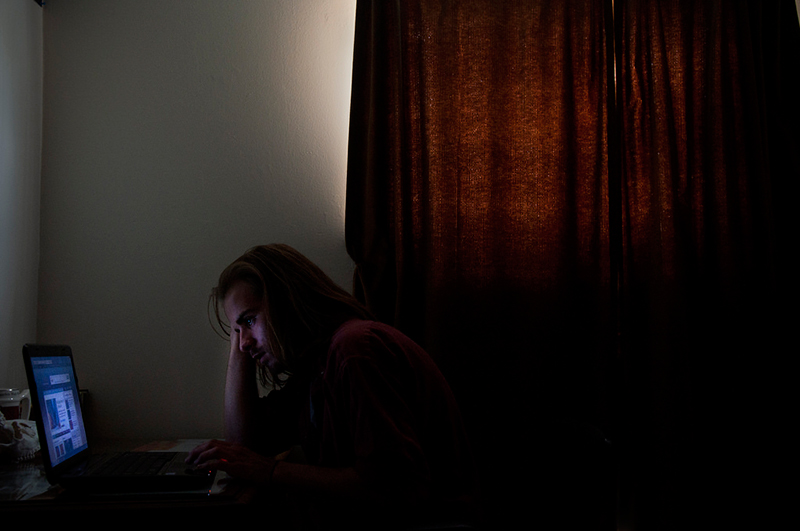

The typical hikikomori's day starts when everyone else's has ended. They're night owls who stay up late, keeping themselves occupied in the bluish glow of TV and computer screens with just their own thoughts for company. Since they tend to initially retreat to their rooms during that existential spiral of doom between graduating from school and starting a career, they almost always live with their parents, who help take care of pesky things like food and shelter. But unlike someone with severe agoraphobia, for example, a hikikomori will occasionally leave their room and even their house, usually to scour convenience store aisles.

The DSM-5, a reference book and diagnostic tool published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), doesn't really mention hikikomori at all and in previous editions, hikikomori isn't considered a psychological disorder, but rather, at best, a symptom of other anxiety and personality disorders. As far as the APA seems to be concerned, hikikomori falls under the umbrella of cultural-bound syndrome, a mental health condition that only occurs in specific cultures for specifically cultural reasons.

Just A Japan Thing?

As unfortunate as it is, there are shut-ins all over the world—not just in Japan—and many of these people are diagnosed as having psychological disorders recognized by the APA. So what gives hikikomori that Japanese je ne sais quoi?

Well, if you read enough news articles about hikikomori, you'll find there's practically a checklist of reasons for the phenomenon to have sprung up only in Japan, but the primary explanation is that Japanese society is one in which there are various hoops everyone is expected to jump through on their way to a successful life and there isn't a whole lot of forgiveness if you stumble. Most cultures are like this to some extent: You go to school, graduate, get a job, then a spouse, etc. But there's also a little breathing room built in, like gap years for "finding yourself" and socially accepted waffling between jobs and even careers.

Not so in Japan where most college graduates are expected to have a job waiting for them before they're even officially handed their diplomas and the current state of Japan's economy makes this task feel all the more insurmountable. The societal shame of failing to get into a good school or get a good job can be too much and staying in your bedroom might feel like the most comforting option.

Sociologists also point to Japan's culture of amae, which is basically childlike dependence on indulgent parents. Tough love is pretty antithetical to Japanese parenting style, so instead of busting down bedroom doors, demanding their hikikomori children retake their entrance exams or continue the job hunt, they do their laundry and cut the crusts off their sandwiches. It's hard to blame them: The path of least resistance is usually the easiest.

Or Is It All In Your Head?

In his book, Saito lays out his rationale for considering hikikomori to be a developmental disorder, rather than the result of colliding forces in Japanese culture. He points out that many psychological disorders first appear during adolescence, and says that the problem at the root of hikikomori is the failure to mature. (Although Saito doesn't claim there is a physiological cause behind hikikomori.)

Hikikomori has a high comorbidity with depression, and people suffering from hikikomori sometimes have other mental illnesses to contend with as well, like schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. However, Saito argues that what would be viewed as a symptom indicative of schizophrenia, for example, like a break from reality is actually a symptom of hikikomori. Those who wouldn't consider hikikomori a disorder would rope the social withdrawal in as a symptom of something else, but it could be just the opposite: The social withdrawal inherent in being a hikikomori causes other symptoms, like depression or obsessive-compulsiveness, to appear. In his work, Saito also says there have been reports of hikikomori cases in countries outside of Japan, particularly South Korea and Italy, further implying that hikikomori may be more than just your average culture-bound syndrome.

The Invisible Hikikomori

When we imagine hikikomori, we usually think of young guys, but a survey conducted by the NHK found that only 53% of hikikomori are male. (Though other experts put the number of male hikikomori at closer to 80%. And here we discover the difficulties inherent in surveying an isolationist population.) Either way, it's undeniable there are women who are hikikomori—they face many of the same cultural pressures as men, after all. (But if we're going with hikikomori-as-bona-fide-mental-illness, it raises further questions as to why more men than women would be affected by this disorder.)

The lack of female representation amongst hikikomori may also simply boil down to the fact that it's more socially acceptable for a young woman to live at home with her parents, which would mean hikikomori among women going underreported and untreated.

Treating Hikikomori

Okay, so if you weren't frustrated enough by the conflicting arguments surrounding the whys and hows of hikikomori, there's also no real agreed upon form of treatment. But the good news is that throwing spaghetti at the wall has had some promising results.

To treat his hikikomori patients, Saito comes at things from a cognitive-behavioral perspective and uses talking therapies, techniques that are also used with patients who suffer from depression or anxiety. Parents of hikikomori are also encouraged to seek out therapy, particularly support groups.

Speaking of, parents of hikikomori have also been known to go the more straightforward route and hire people to bust down bedroom doors to literally drag their kids out. (Even the stolid principles of amae have their breaking point, apparently.) Suffice it to say, this particular solution has not proven terribly successful and has mostly been abandoned at this point.

In the realm of creative problem-solving, some organizations and halfway houses like New Start employ young women to physically go to the houses of hikikomori and try to strike up a conversation from the other side of the bedroom door. The goal for these "rental sisters" is to ultimately reassure, befriend and then coax the hikikomori out of their bedrooms and to a place where they can get help.

A company called Avex has even produced a collection of videos called "Just Looking" in which girls look straight into the camera for a minute or so. The idea is that hikikomori can then get used to maintaining eye contact, while still in the comfort zone of their room. See how well you can keep eye contact with the little girl in the video below, I dare you.

But beyond the power of a pretty girl or talking therapies, I think the most promising source of healing and treatment is coming from ex-hikikomori themselves, like Kazushi Suganuma, who, with the help of his brother, opened a coffee shop where recovering hikikomori can work and experience responsibility and daily social interactions.

Even though the question of whether hikikomori is a true psychological disorder or not is a valid one, particularly when it comes to figuring out useful therapies, the people who may be best suited to addressing Japan's social withdrawal problem are ex-hikikomori themselves. And as more hikikomori enter the world again, hopefully they can use their own first-hand experiences and bring other hikikomori out of the dark.