Many of you probably recognize Narita Airport as your gateway to Tokyo and wider Japan. And, if you’re one of the 35,379,408 passengers who used Narita last year, you were able to experience this airport in its full glory.

Japanese restaurants, cleanliness, souvenir shops and the Narita Express are probably the first things that come to mind. But in fact Narita’s opening and its subsequent few decades were mired in controversy, mortars, people chaining themselves to houses and train arson. Hold on, I’m getting ahead of myself, here.

Narita’s Beginnings

Narita didn’t use to exist. In fact, for a very long time Haneda Airport (opened in 1931) was the main airport serving the Tokyo region and still beats Narita in terms of passenger numbers and number of flights in and out of it.

However, as Japan started growing at a breakneck speed in the 1950s-1960s there was a pressing need to expand airport capacity – not just because of the increase in international cargo but also because of the increasing number of jet planes in use. Haneda’s capacity was full and expanding it was considered to be nonviable given the lack of land and other problems.

Given this, the Japanese government decided to develop a second airport to serve international flights in the wider Kanto area in the 1960s. The (then) Ministry of Transport considered a number of candidate sites before settling on the Sanridzuka area of Narita City in Chiba Prefecture.

Trouble

When you want to build an airport, you need land. And the problem then was how to get it. Around 40% of the land for the airport at that time was imperial property and thus could be gained by the Japanese government. The rest was agricultural land owned by the various farmers living in the area.

They (the farmers) were infuriated with the announcement as there were no agreements with the local authorities and there was no prior explanation of the central government’s plans. Thus, the Sanrizuka-Shibayama Union to Oppose the Airport (referred to as the “Union” below), a loose coaltion of local farmers, student protesters etc., was formed.

This was originally supported by mainstream political parties such as the Japanese Socialist Party and the Japanese Communist Party but as the government virtually ignored the protester’s objections to the airport’s construction, the Union’s methods and ideologies became increasingly hardline. “Fight force with force” became the motto, causing mainstream parties to rescind their support. In return, however, far-left-wing radicals of the violent revolution-type joined, protesting that Narita would be a new military air-base for the US to use in the case of war with the USSR.

The government originally tried to buy over land in the area with the agreement of landowners. However, with land purchasing not going well with a significant number of landowners refusing to sell their land, the government decided in 1971 to forcefully evict the residents in the area, which is legal by Japanese law. As you can imagine this added fuel to the fire.

Violence

Even before the forced evictions there was violence. The riot police were first called in after a sit-in in 1967. Frequent clashes involving thousands of protesters and riot police frequently occurred. The protests became even more violent after the forced evictions – with 3 riot police members killed in a confrontation in 1971 after being ambushed by protesters (known as the Tōhō Jūjiro Incident).

Other incidents around the time include:

- One Union protest leader running for the Japanese Diet (parliament) ran on a Narita Airport opposition platform. Despite getting 330,000 votes nationwide he failed to win a seat.

- Protesters built a steel tower in the area to obstruct construction of a road to the airport.

- Numerous incidents of counter violence from security forces on protesters, including one death during the destruction of the above mentioned tower.

- The construction of a “fortress” using 100 million yen worth of donations on an area near where protesters expected planes to land. Battles between riot police with tear gas grenades and water cannons and protesters with Molotov cocktails and pachinko-ball slingshots took place when the authorities tried to clear it away.

- Arson against a Keisei Skyliner train to sabotage transport to Narita.

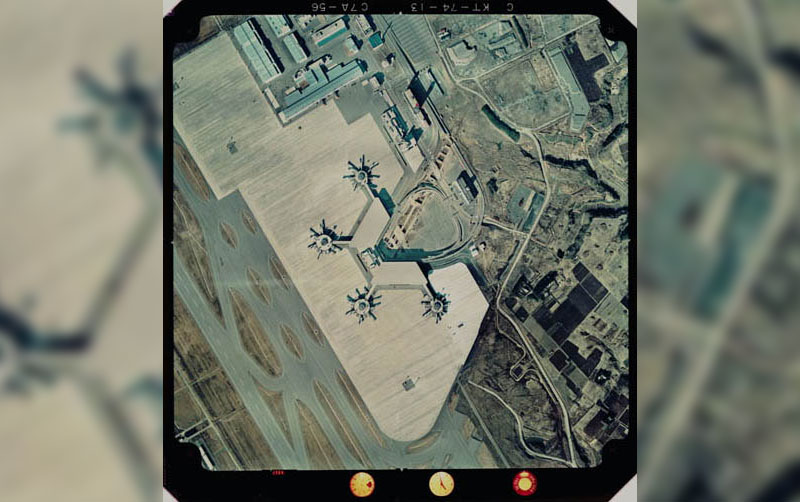

Perhaps the most “attention worthy” of these attempts was the occupation of the control tower (pictured above) by the protesters which involved ramming two trucks carrying waste oil through airport entrances and a “red helmet squad” infiltrating the airport vicinities overnight through sewage pipes. They succeeded in destroying the equipment of the airport control tower.

Opening of the Airport

The above efforts were massively successful in getting the opening of the airport delayed; the original plans were to open Narita Airport in the early 1970s but Narita only finally opened on the 20th of May, 1978.The next day the first flight, a JAL freight flight from Los Angeles, successfully landed in Narita.

This didn’t mean that the troubles ended though. On the opening day a Union rally attracted around 22 thousand people and they declared a continuing campaign of resistance against the airport and clashes occurred between riot police and protesters. In the September of the same year, protesters even managed to hit a plane landing in Narita with fireworks. Numerous arson attempts continued against pipelines providing fuel to Narita as well as Narita-bound Keisei trains.

However, resistance activity has largely died down in the years since then. For one, the original Union failed in its ultimate quest – stopping Narita from opening. With Narita opened and the chance of its closing becoming increasingly remote the movement gradually lost steam. Furthermore, radical left-wing movements were in the decline overall by the 1980s and internal fractures split the Union movement, severely damaging its influence and credibility.

The government also started adopting a more conciliatory tone in the 1990s, starting with the holding of a symposium regarding the various issues surrounding Narita Airport, land issues and the like. This culminated in (then) Prime Minister Murayama’s apology to the affected residents in 1995. This led to a softening of stances from the remaining protesters.

Implications

It’s not all over though. The above photo is a relatively recent photo of a protest sign (the picture says it dates to 2009) and in 2008, 2 mortar cannons were found in the woods near Narita.

It is because of this that Narita has such tight and strict security – which some of you may have experienced. Police on the trains, passport and boarding pass checks for all visitors to the airport are all measures going back to the days of the protests.

The whole fiasco over Narita also caused changes in policy for the other airports in Japan. People who live in Osaka and Nagoya (as well as visitors flying into these cities) may notice that the international airports for these cities have been built on artificial islands in (to be frank) the middle of nowhere. This was a key lesson learned from Narita – instead of wrangling over land ownership with unhappy residents, it’s much easier and less of a headache to just simply build your own land and build your airport on top of it.

The Future of Narita

Nowadays most visitors using Narita probably do not know about the ruckus which Narita’s construction entailed – the strict security checks and the museum may be a few of the more obvious indicators of the prior conflicts.

Narita faces new challenges though. There is currently quite a bit of pressure on it to expand its capacity from airlines. Furthermore, Haneda Airport restarted serving international flights in 2010 – Narita is thus facing increased competition.

Furthermore, having to apply such beefy security systems has been a drag on Narita’s operations. First of all, having to hire so many people to do the security work is not cheap. Secondly, the extra security checks cause all kinds of bottlenecks. Reforms have been announced such as the introduction of CCTVs over manual checks to hopefully decrease the burden that the checks cause.

But so far Narita Airport is doing well. It’s still the number one international airport in Japan and while Haneda has more people and planes using it, Narita is the No. 1 airport in terms of freight value and even exports more than the (sea) port of Tokyo (source).

So, I hope you think about all this history the next time you fly into Narita. It’s not just an airport, it’s a place that affected thousands of people’s lives with a rocky history that didn’t calm down until relatively recently.