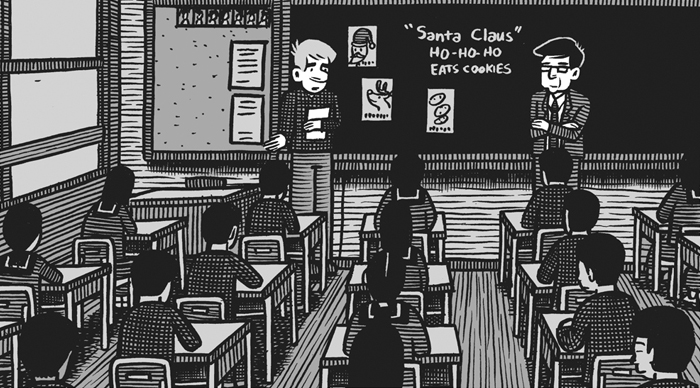

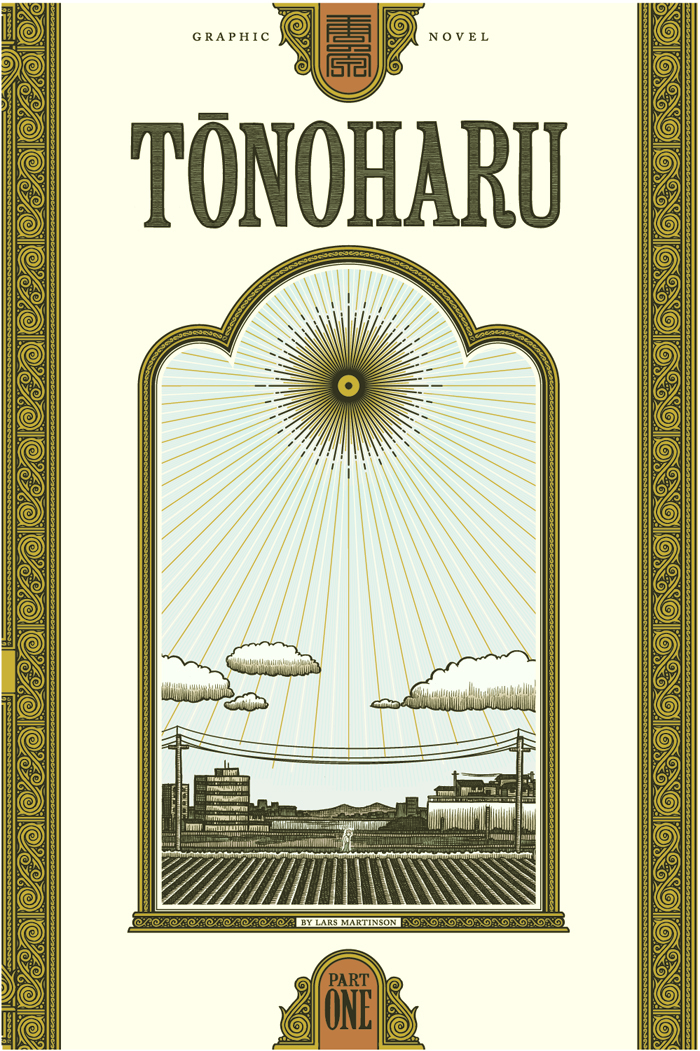

As an alumni of the JET Program, I get asked what it's like teaching English in Japan. To answer that, I point to the introduction of Tonoharu Part 1. The first sixteen pages of this graphic novel illustrate the experience very accurately, complete with triumph and frustration.

The author, Lars Martinson, drew on his own experience on JET in creating Tonoharu. The story is ambient and introspective, emphasizing the day to day events of life abroad. It follows fictional ALT Dan Wells as he adjusts to life and work in Japan. Mastinson guides Dan through the story and keeps him balanced. The reader looks down on Dan's actions in one scene and sympathize with them the next. This expertise makes Tonoharu more than a mere parody of English teaching in Japan. It is a fully realized story about it. This in itself is rare.

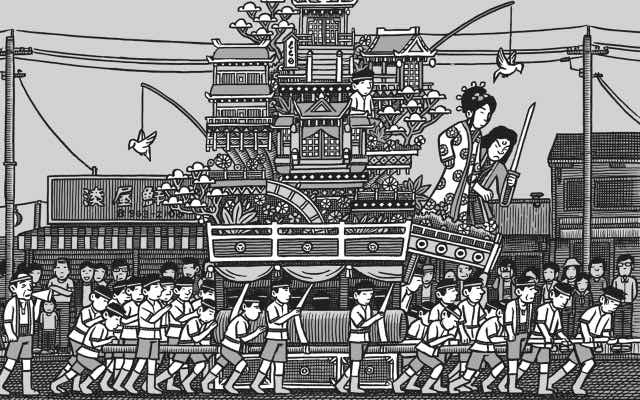

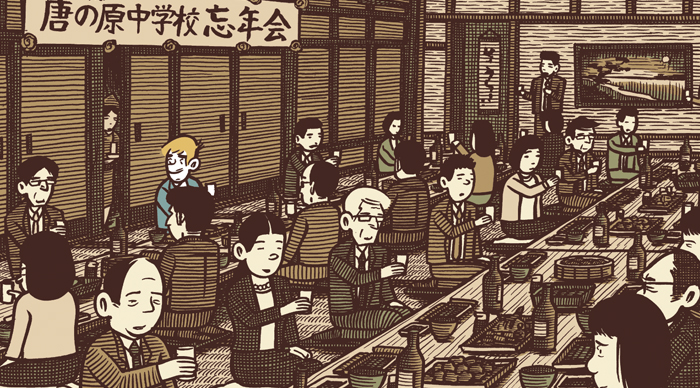

The art, of course, is what draws most people to Tonoharu. Martinson's style is reminiscent of the Belgian artist, Herge. The intricate backgrounds contrast with the simpler character designs, allowing the reader to inhabit the story's environments. Of course, there is little I can say that the art itself can't say better.

Martinson studied East Asian Calligraphy for two years in Fukuoka after finishing JET. His personal approach, combined with the traditional inking technique, really makes for something special. The art alone is worth the price of admission.

I had the opportunity to talk with Lars and ask him about his work. Below are insights into his stories, his art, and his process.

For those who may not know, who is Lars Martinson?

I'm an American cartoonist that has spent half of his adult life in Japan. For the past decade I've been working on a graphic novel series entitled Tonoharu.

What is Tonoharu about?

Tonoharu tells the story of a young American who moves to rural Japan to work as an assistant English teacher. It is based (in part) on my own experience doing the same from 2003 to 2006.

Because Tonoharu is fictional and not a direct telling of your Japan experience, what inspired you to tell this story? Did you have an "aha" moment?

I've always been frustrated by how hard is it to relate my experiences in Japan to friends and family back home. It's sort of like when you try to describe a dream to someone. It's fascinating to you because you experienced it firsthand, but it's almost always tedious for the listener because they don't have the same frame of reference. My inspiration to create Tonoharu came from a desire to bridge this gap; to describe the experience of living abroad in a visceral way.

You've mentioned elsewhere that your main character, Dan Wells, is not based on you. That said, how do you as his creator feel about him and his decisions? Was he difficult to write?

I'm certainly more driven than Dan. I made much more of an effort to improve my Japanese abilities when I first arrived in Japan, and have a clearer sense of what I want to do with my life. That said, I share a number of qualities with him, so he wasn't hard to write. Like Dan I'm introverted, and often struggle to form meaningful connections with people around me.

How much Japanese did you know when you went on JET? How did the language barrier affect your experience?

I knew very little Japanese when I first arrived. Just a little bit of hiragana and katakana, and basic grammar. It improved quickly, but even now I feel like I have a long way to go. I heard somewhere that you can become fluent in three European languages in the same amount of time it takes to learn Japanese, and I believe it. It's a huge undertaking.

One interesting consequence of my mediocre Japanese abilities is I tend to be more forthright when I speak it. It's easy to be evasive in English since it's my native tongue, but in Japanese I don't have the language skills to dance around the subject. So I'm forced to distill what I want to say down to its naked essence.

There's a Dostoyevsky quote that goes "Stupidity is brief and artless, while intelligence squirms and hides itself. Intelligence is unprincipled, but stupidity is honest and straightforward." I feel like this applies to how I use English compared to how I use Japanese.

Your main character, Dan, goes through a difficult bout of negative culture shock in the first volume. Did you have a similar experience?

Most people who live abroad experience culture shock to some degree, and I'm certainly no exception. I sometimes worry that I favored those negative moments a little too much in the first volume of Tonoharu, because many people who read it seem to assume I had an unequivocally horrible time in Japan, which certainly wasn't the case at all.

You went back to Japan to study calligraphy for two years after finishing JET. How did that trip affect your art and your relationship with Japan?

Before I really got into it, I had no idea how deep East Asian calligraphy is, both in terms of history and technique. I'm now convinced that it's the most sophisticated line art tradition in the world, hands down.

When a cartoonist wants to improve their penciling, they usually study Western art fundamentals such as perspective, anatomy and composition. I would argue that Eastern art fundamentals are just as useful to learn comic inking. Practicing East Asian calligraphy has improved my inking more than anything else I can point to.

Regarding your calligraphy learning experience, was it more of a disciplined practice that enhanced the skill you already had or was there something inherent in East Asian calligraphy that got added to you? Do you have any stories about the learning experience?

The discipline was certainly a huge part of it. Art classes in the US tend to emphasize personal expression over technique, so student critiques can be vague and coddling. The calligraphy classes I took in Japan were the exact opposite. We would be tasked with replicating a piece of classic calligraphy as accurately as possible. We'd show our attempt to the professor, who would point out where we went wrong, and we'd try again. They were technical exercises rather than creative ones, but they helped me learn how to control the brush in a way I never would have if left to my own devices. These skills, in turn, benefited my creative work.

Beyond technique, East Asian calligraphy has a number of qualities that informed my development as a cartoonist. It'd be too lengthy to get into here, but if anyone's interested I wrote a few entries about it on my blog.

What inspires you as an artist in the realms outside of comics?

I've always been fond of stories told through pictures, so most of what inspires me has visual and/or narrative elements. Wong Kar-wai movies, Knut Hamsun novels, and Hokusai's sketchbook collections spring to mind as sources of inspiration. For music I really like Scandinavian folk; Hedningarna and Triakel are particularly good.

Recently I've become intrigued by the narrative potential of video games. I played Persona 4 Golden on the Vita last year, and it's taken a place among my favorite narrative experiences in any medium. It paints a surprisingly subtle and nuanced portrait of a Japanese school life for a game that features demon-summoning and serial murder.

What is your favorite manga or manga artist? What draws you to that manga/artist?

I read tons of translated manga when I was in high school. Favorites at the time included Masamune Shirow, Johji Manabe, and Rumiko Takahashi. Eventually my interests drifted elsewhere, so I have to admit I'm not too familiar with the current manga scene. My favorite manga these days is hardly cutting edge: "Sazae-san" by Machiko Hasegawa.1

What has been the reaction of Japanese people who have read your graphic novel?

More than anything Japanese people tend to be surprised by the format. The Tonoharu books are hardcovers with two-color interior pages, which is all but unheard of in the manga world. Manga is usually first serialized in weekly or monthly black and white anthologies, so creative choices such as page sizes and printing methods are out of artists' hands. Conversely, anything goes for American indie comics, so there's a lot more diversity in terms of presentation, use of color, and binding.

Many of our readers have expressed interest in moving to Japan to become manga artists. What advice do you have for them?

I've never actually worked in the Japanese comics industry, so I'll refrain from speculating on that in particular. But in broader terms, I wouldn't advise pursuing a "career" as an artist unless you can't imagine being happy doing anything else.

By some measures, Tonoharu has been a massive success; it's been covered in the Wall Street Journal and Entertainment Weekly, translated into French and Spanish, and has sold out two hardcover printings. But for all that, I've never made anything even approaching a living wage off of my work. Granted, I don't have many books to sell, since I work at a glacial pace (spending more than ten years on three books is pretty ridiculous). But either way, trying to make a living as an artist rarely makes financial sense no matter how productive you are.

That said, I'm certainly not trying to dissuade people from pursuing something they're passionate about. Obviously I wish I made more money from my comics, but I don't for a second regret creating them. I guess my advice to someone looking to work in the Japanese comics industry would be the painfully obvious; strive to improve your craft as much as possible, and become proficient in Japanese. And make sure you're having fun doing it, because there's a good chance it may not provide as much monetary compensation as you'd like.

Tonoharu Part 2 ends with a cliffhanger. What is in store for Dan in Tonoharu Part 3?

With each book, I've tried to capture different aspects of the experience of teaching in Japan. Notably absent in the first two books is any sort of meaningful interaction between Dan and his students, so I devote a significant chunk of the third book to that. This makes for some of my favorite scenes in the whole series, so I hope readers enjoy it as well.

What is your opinion of Japanese cake?

Almost always disappointing.

Hardcover editions of both parts of Tonoharu are available here:

For the tech-savvy, Martinson's more light-hearted e-comics are available here: