Great.

Another gasbag movie-nerd is gonna talk about the American version of The Ring and how it pales in comparison next to its seminal Japanese horror inspiration Ringu (or vice-versa). Maybe he’ll talk about how one of the ghost kids was spookier than the other, or address the physical differences between the corpses of the poor hapless teenagers. I can’t waaaaaaiiiit…

Wrong, pal.

Rather than join the ranks of those who prefer to get hung up on the surface-level differences between the Japanese film and its American counterpart, I believe each movie is necessarily different to serve its own unique purpose. These differences help us to better understand which aspects of Japanese culture bleed (hehe) into Western culture, and what just doesn’t translate. And that’s why we’re all here, right? To not only celebrate Japanese culture, but to figure out why it draws us in?

Disclaimer: if you’ve never seen Ringu or The Ring and don’t want the experience of watching either ruined for you forever, I would recommend not reading this. I would also recommend immediately watching one or both of these movies because what the heck are you doing man?

Ringu (1998)

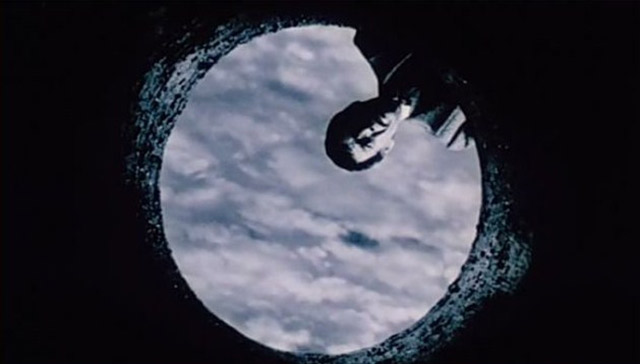

Hideo Nakata’s Ringu is a horror story that is universally enjoyable and terrifying, while its roots are uniquely Japanese. The movie is an adaptation of Koji Suzuki’s novel of the same name, which was inspired in part by the ghost story Banchou Sarayashiki, or the story of Lady Okiku (lots of inspiration going on here). There are several versions of Okiku’s story, but they all involve her being thrown down a well after losing one of ten valuable plates belonging to an important samurai family. Legend says that her ghostly voice can be heard deep within the well counting up from one as she rechecks the plates. Stopping short at nine, she lets loose a heart-stopping shriek before her specter rises from the well in search of the missing tenth plate.

In Ringu, several young people are mysteriously dying after watching a strange videotape. A reporter, Reiko Asakawa, discovers the tape and learns that it is cursed by the vengeful spirit of a young girl who died after being thrown into a well. After watching the tape, Asakawa comes to find that in seven days the girl will rise from the well and kill her. Counting the days…counting plates…rising from the well…wait a minute, this is starting to sound familiar!

The Ring (2002)

Now for the American version. After several teenagers are mysteriously killed, a reporter, Rachel Keller, discovers that an eerie videotape contains the culprit. Within the tape is the vengeful spirit of a young girl who…yeah you get the point.

Gore Verbinski’s The Ring was wholly inspired by the international success of Ringu. This is a story that has played out many times in cinema history: one country hits a goldmine, so it’s only natural that other countries want to emulate their success. The thing that separates The Ring from these thousands of other remakes that came before and after is that it was was remade incredibly well. Love it or hate it, The Ring affected people the world over just like Ringu had done before. What was miraculous about the American Ring however was that it was also effective and popular for different reasons than its predecessor, even though the plot is more or less exactly the same. Many scenes and situations were altered so that they would translate better for American movie-goers, while some remain exactly the same. Within these changes and similarities are the keys we need for understanding how Ringu and The Ring jointly channel / filter the Japanese and Western cultures.

Youth Culture

After the opening of both films, the protagonist goes to the wake of her niece whom we just watched die. Within these scenes, the protagonist talks to a group of schoolgirls who are mumbling something or other about a video, about other kids who have died, that kind of cheerful stuff. But these groups of schoolgirls are much different from each other in the American and Japanese versions.

In Ringu, the girls are dressed in school uniforms, representing the all-girls’ school the deceased girl went to. They are quiet, timid, and seem a bit embarrassed when Asakawa approaches to ask them what they know about her niece’s death. With some regret, they tell her about the cursed video and other deaths they’ve heard about.

In The Ring, these same girls are not exactly in uniform, nor in appropriate funeral garb to boot. They are on the porch of their deceased friend’s house smoking cigarettes and gabbing amongst themselves. When Rachel approaches the girls to gather info, they act coldly and all but ignore her (buncha real jerks, they were). Rachel feels some need to prove that she’s not some old fuddy duddy to these teens, so she pulls out a cigarette herself and starts to talk about how she and an old friend used to get high together. The girls still offer up little to no information.

What does this say about Western youth culture, and the level of respect that is normally shown to our elders? Of course there are disrespectful young people everywhere, even in Japan. But doesn’t this drastic change to the film make sense in the context of our differing cultures (which is ding ding ding what we’re talkin’ about here)?

In Japanese culture, it is important to be respectful to people in a higher position, especially those who are older than you (even by a couple years, senpai!). So even though the girls obviously don’t wish to tell Asakawa about the tape, they seem to feel it’s necessary based solely on the fact that she is an older woman who has asked something of them. So respectful…bad kids everywhere take note!

A Father’s Responsibility

We are introduced to the fathers of the protagonist’s children in exactly the same way in both films: while walking to school in the rain, a boy nearly walks into a shady looking man on the sidewalk. For a brief moment their eyes meet, then they part ways and walk in opposite directions. There is no father-son connection in either movie.

The father in The Ring, young Noah, is an immature airhead. There are moments where we are able to see that he wants to be around for his son, but strong self-doubt and a shaky past with his own father keeps him from being around. Strong family ties are not exactly the pinnacle of Western culture. Is it possible Noah’s character might represent a vicious cycle of broken fathers begetting broken sons?

The father in Ringu, Ryuji Takayama, is an accomplished professor at a local university. We are never given too much history into their romantic past, but Takayama and Asakawa’s marriage obviously didn’t work out too well. Mr. Big Shot Professor seems to live only for his work, publishing essays and constantly scribbling mathematical equations down. His son is of little concern to him. Takayama has a different set of priorities. It’s work before family – you saw this recently in our What It’s Like Dating A Japanese Guy post.

In Japan, careers are drilled into the minds of almost everyone at a young age as being vitally important. It is not uncommon to hear about people overworking themselves for coveted positions in the workforce. A father who values his work over his family is a common trope that resonates deeply in Japan, where work ethic is so heavily cemented in the culture. Professor Takayama is a harrowing example of valuing work over family.

While both fathers have the same character arc, act in similar fashion, and endure the same fate, the reasoning behind their actions are surprisingly different, given where they come from.

A Mother’s Love

Unlike everything I’ve talked about so far, the mothers in both films are the only characters that are perfectly in sync: no matter where you are in the world, a mother’s love is universal and enduring.

Asakawa and Rachel are both called to action when they realize the validity of the cursed tape, but are only one hundred percent spurred on when their children watch it too. Given, motherly instinct is nothing new…unless it’s also directed at a child that is not biologically your own.

As the mothers race against the clock to uncover the mysteries of Sadako (Ringu) and Samara (The Ring), a growing sense of sympathy begins to emerge behind their actions. In the corpses of these children, the women see young girls who died just wanting to be loved. Embracing a skeleton dripping with goo is no small feat. I imagine it would take a whole lotta love and understanding to hug a corpse.

Don’t think that I’ve forgotten that Sadako and Samara were killed by their father and mother (respectively). The reason I haven’t included them at all is because they are not representative of parenthood, they are simply used as devices in the narrative. When effort was put into showing that they were not biological parents in both films, I think I can say this with some certainty.

Sadako and Samara end up being completely nuts and evil, but before they go off the deep end, at least they unwittingly show us something beautiful about parental instinct and motherly love.

Hopefully, without getting too spooked, you learned something about love or vicious cycles. Or cigarettes. The lessons in Ringu and The Ring are seemingly endless, right? (Hint: don’t watch TV ever again.)

Japanese films that are remade for Western audiences are rarely as good as Verbinski’s The Ring, but they all present opportunities to compare and contrast our cultures.