As the World Baseball Classic comes to a close, I think it has become clear that Japan is indeed a force to be reckoned with in terms of the world of baseball. Sure, they didn’t win it this year, but another trip to the championship round after winning it all the previous two Classics isn’t all that shabby. On top of this you can take a look at Japanese baseball stars who have made it to America, like Ichiro, Hideki Matsui, Hideo Nomo, Yu Darvish, and Kazuhiro Sasaki, and know that there’s quite a bit of talent out there.

But it wasn’t always like this. Japanese baseball had to start somewhere, and it turns out that somewhere was quite a long time ago, sometime in the 1870s, to be exact (or as exact as possible). But how did baseball come to Japan? It certainly wasn’t anything like Samurai Champloo’s rendition, though one can dream.

Instead, Japanese baseball got off to a slightly less dramatic start. Of course, as it is an American sport, we have to start this story with an American.

Japanese Baseball Is Born (1870's)

Most people credit American Horace Wilson (1834-1927), an English professor at Kaisei Gakko the predecessor to Tokyo Imperial University. He had spent some time in Japan before this, though. He also helped as a foreign adviser for the Japanese government to assist in the modernization of the Japanese education system. To say the least, he had some experience in Japanese education.

The thing is, before Horace Wilson, there weren’t really any team sports in Japan. You had Sumo, kendo, kyudo, and other one-on-one physical activities, but something that involved teams? Not really. I do find this a bit strange considering how group-based Japanese culture is and was, but nonetheless it really explains why Japan has embraced baseball the way it has. It also explains a lot of the differences in how it’s played.

Professor Wilson can’t be credited for baseball’s popularity in Japan, however. Albert Bates, an American teaching at Kaitaku University, also cannot be credited with the “birth” of Japanese baseball, though he did organize the very first game in Japan. No, that credit goes to Hiroshi Hiraoka, a Japanese railway engineer who was a student in America (not to mention a huge Boston Red Sox fan). He was the one to organize the very first Japanese baseball team, known as the Shinbashi Athletic Club Athletics. So, in 1878, Japanese baseball was officially born.

Due to being the very first Japanese team ever, the Shinbashi Athletic Club Athletics had the best Japanese baseball team in Japan and (in my opinion) the worst name ever. We get it, you’re athletic. Other teams started popping up in Japan following their founding, but nobody could really keep up in skill for nearly ten years.

Team Ichikou (1886)

Team Ichikou, the “First Higher School of Tokyo” (aka super prestigious prep school), was founded in 1886. Apparently they were pretty good. So good, in fact, that they thought they could challenge the whites-only Yokohama Athletic club (yep, there were non-Japanese baseball teams in Japan at the time, they just didn’t want to play with the Japanese). Of course, being a whites-only baseball team, they went ahead and refused the challenge. Upon hearing about this, the Christian Missionary school Meiji Gakuin offered to play Ichikou. Turns out, all that Ichikou prep school life didn’t “prep” them for such a decisive defeat. The Meiji Gakuin team destroyed them, but it opened their eyes as to how much training they needed to do.

Ichikou players began a practice regimen that would bring them to the point of complete physical exhaustion. Why? So the team can get better as a whole. This isn’t too much different from the practice philosophies of sumo or kendo. Now we can see some crossover between Japanese sporting culture and this American sport. This style of practice would (and still does) continue to stick around throughout Japanese baseball history.

They practiced like this for ten years, and in 1896 the Yokohama Athletic Club finally accepted their challenge. Guess what? All the vomiting and blood-urine paid off, apparently. Team Ichikou crushed the whites-only Yokohama Athletic club by a score of 28 to 4. It was also the first ever recorded international baseball game in all of Asia.

Due to the win and fervor behind this, many universities began to play baseball and the sport gained popularity in Japan.

Universities Era (1900-)

As baseball in Japan gained popularity, the most obvious place for teams to sprout was in the universities. As teams became more competitive, schools would send students to America to learn and get better. In 1905, Waseda University was the first team to do this, and many other schools followed suit to keep up. American teams also began to reciprocate, sending teams over to Japan to play in exhibition games as well as to teach Japan a thing or two about American baseball.

It was also in this time that the rivalries begin to pop up. One such rivalry, between Waseda and Keio University, still goes on today. It even has a name (the Sokeisen 早慶戦) and people go nuts over it, classes are canceled, and it is even broadcast on national television. It has gotten so rowdy that games get canceled, which seems ridiculous considering that people get rowdy because they’re super excited about the games. In fact, there was a two decade period where the games were banned because people got too crazy about it. That should give you an idea how big of a deal this is, anyways.

Growth in Universities continued to happen, and American amateurs would play baseball with Japanese amateurs. But, Japan was starting to get serious about baseball. America took some notice to this.

- 1908: A mix of minor and major league players known as the “Reach All-Americans” visit Japan and other countries to play baseball.

- 1913: The Chicago White Sox and New York Giants play in Japan with Japanese teams.

- 1920s: Major League Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis helps to send a team of major and minor league players to Japan to both play games and run coaching clinics.

Over twenty or so years, we see quite an increase in Japanese baseball skills. More and more people are coming from America to help out, and Japan keeps getting better. Universities establish themselves as the Japanese baseball force of this era, so much so that they eventually form their own league.

“The Tokyo Big6” (1925)

In 1925, the Tokyo Big6 league was established. It basically consisted of the six best and most established collegiate baseball teams in Tokyo. The league still exists today, and of course the rivalries do as well. The teams and their all-time records are:

- Waseda University (1197-703-83)

- Keio University (1110-797-87)

- Meiji University (1139-780-97)

- Hosei University (1113-795-109)

- University of Tokyo (244-1520-55)

- Rikkyo University (851-1058-91)

Can we just take a moment to feel really bad for the University of Tokyo? They’ve come in last place in 118 of the league’s 156 seasons. Their best ever season was when they came in third… but it was also a season in which both Meiji University and Waseda University did not play, so… yeah, ouch.

Besides University of Tokyo, however, the Big6 were powerhouses of Japanese baseball talent. Even University of Tokyo was pretty good when you compared them to most Japanese baseball teams outside of the Big6. But, they had to get better. That’s where good ol’ “Lefty O’Doul” comes in.

The “Father” Of Japanese Baseball: Lefty O’Doul (1932)

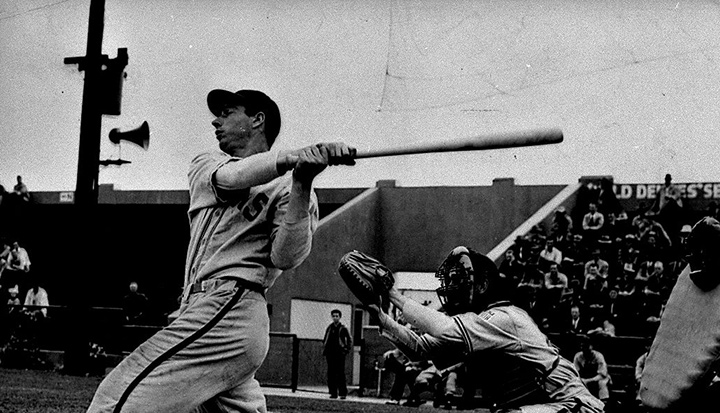

Some people call Lefty O’Doul the “Father of Japanese” baseball. There’s a reason for this. Not only was he a great American baseball player (started as a struggling pitcher, switched to being a hitter, had a .349 batting average over seven seasons winning the batting title twice), but he invested a lot of time and effort into the Japanese baseball scene as well.

The first time he went to Japan was in 1931. This was during a trip that involved baseball trips to China and the Philippines as well. But, something must have stuck, because in 1932 he went back for almost three months. Lefty, Ted Lyons, and Moe Berg held 40 lessons at each of the Big6 schools. There were also Americans with them that played in exhibition games with the Japanese that drew crowds of over 60,000 people. Baseball, it seems, was a big hit in Japan. The American baseball players were celebrities, and Japanese baseball grew leaps and bounds over the years thanks to Lefty O’Doul and friends. He came back every year from 1933-1937.

1934, however, was one of Japan’s best pre-war baseball years, though. And of course, it was all thanks to Lefty.

Striking Out The Pros (1934)

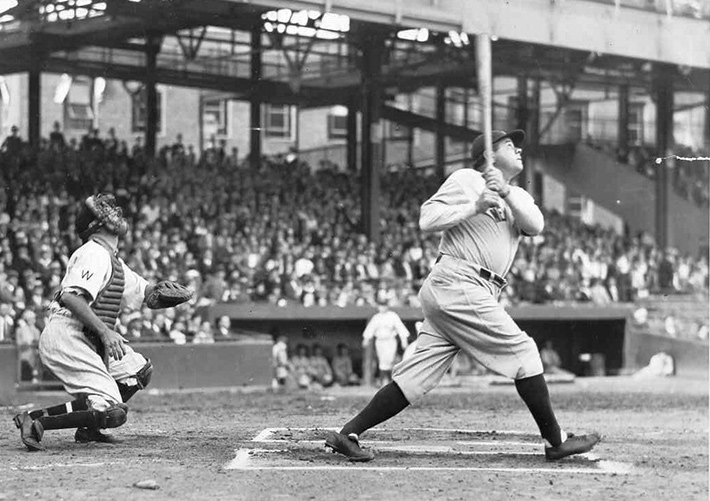

In 1934, Lefty O’Doul got together a group of All-Star players from America and brought them over to Japan. Players included Earl Averill, Lou Gehrig, Lefty Gomez, Babe Ruth, Earl Whitehill, and more. It was a pretty good American team. In order to face a team as stacked as this one, Yomiuri Shinbun (newspaper) owner Matsutarou Shouriki brought together Japan’s version of the dream team. Despite this, they lost all 18 games that they played against the Americans. I mean, I guess it makes sense, but that’s a lot of losses. Still, perhaps it gave Japan the shock they needed, just like team Ichikou of 1886.

One particular instance out of these 18 games stood out, however. Pitcher Eiji Sawamura became a national hero when he struck out Charlie Gehringer, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx… in order. I suppose over 18 games it was bound to happen, but it was the sort of thing that Japanese baseball needed to really light a fire under everybody’s pants. Baseball was more popular than ever, so in 1935 Matsutarou Shouriki kept the dream team together and took a tour of the US and Canada to play more baseball. By 1936, they had gone pro.

Japan’s First Professional Baseball Team (1936)

I’m not sure if calling yourself “professional” is enough to be professional, but apparently this time it was. Shouriki’s team was the first and only team to join the “Japanese Baseball League.” Their name? The Tokyo Giants. One may wonder where they “found” the name the Giants, and one may wonder correctly if they thought of the New York Giants. But, it wasn’t just on a whim. It was a sort of “thank you” to Lefty O’Doul, who brought over the American All Star team that got the Japanese team together in the first place. O’Doul was a New York Giant, so they would be Giants too. The name is still around today, though very few know it was thanks to Lefty that they got the name.

Soon after, six other teams would join the party. The Osaka Tigers, Hankyu, Dai Tokyo, Nagoya Kinko, Nagoya Dragons, and the Tokyo Senators. As is often the case today, many were sponsored by newspapers hoping to cash in on baseball’s rising popularity. If you run the newspapers, you run the news. If you run the news, you can promote your baseball team quite a bit, make more money, and then get better players. If you weren’t a newspaper, though, you may have been a train line (Tigers and Hankyu). If people want to see your baseball teams play, they’ll ride on your trains. I think it’s funny how the whole sponsorship thing panned out.

Strangely enough, the Tigers became the team to beat for quite a while (until 1939). Then, the gained dominance until World War II brought an end to Japanese baseball… at least temporarily.

World War II Strikes And You’re Out?

The war brought much strife to everything, including a little bit of said strife to baseball. Lefty O’Doul started to become upset about Japan’s rise in militarism, which of course meant a lot less Japanese-American baseball friendships. The Tokyo Giants changed their name to the Tokyo Kyojin (also means “giants,” but now it’s Japanese), the Osaka Tigers became the Osaka Hanshin, and the Tokyo Senators became the Tokyo Tsubasa.

In 1939, the Japan Baseball League combined their “split season” into one single season of 96 games. In 1940, they expanded to 104 games. During these years there were nine teams in the league. Things were still going well for baseball, despite the war. Then things got bigger. Resources and people began to get thin. In 1941, the number of games were reduced to 84. Despite this, they ramped back up to 104 games in 1942. Then, things got worse for Japan’s war effort. 1943 saw 84 games once again, 1944 saw only 35 games with six teams, and 1945 never happened. You can probably guess why.

Still, baseball was hardly dead in Japan. In fact, things were just getting started. I think it really took the end of the war, American occupation of Japan, and a few big events to allow Japanese baseball to blossom. None of this happened until after the war, though, so let's get through that.

Occupation Baseball (1945-)

For some reason, it was right after the war when Japanese baseball really blossomed, I would say. It took only nine months into the occupation for the Japanese pro leagues to make their way back, thanks to the support of the Allied troops (they rightly thought it would be good for morale) and large corporations (who financed the baseball teams’ returns). Things started up again with eight teams playing 105 games. Not bad considering they only played an average of 77 games per year from 1941-1944.

Obviously, baseball needed quite a bit of help to bounce back from the war. If you think about it, most of the players were probably drafted. On top of that, a lot of the talent also probably met injury or death. Still, the teams were back and people were playing baseball… but who could be the icing on the cake? Who could bring the fire back into Japanese baseball? How about the man who was known as the “Father of Japanese Baseball”? That’s right, good ol’ Lefty O’Doul is back for round… er… inning two.

Return Of The Lefty (1949)

Lefty O’Doul was pretty upset by the militarism shown by Japan leading up to the war. He was also, understandably, not too happy about Pearl Harbor. But, this was a new era now, so Lefty let bygones be bygones and came back to Japan in 1949 to rekindle that Japanese-American baseball bond that had gone missing.

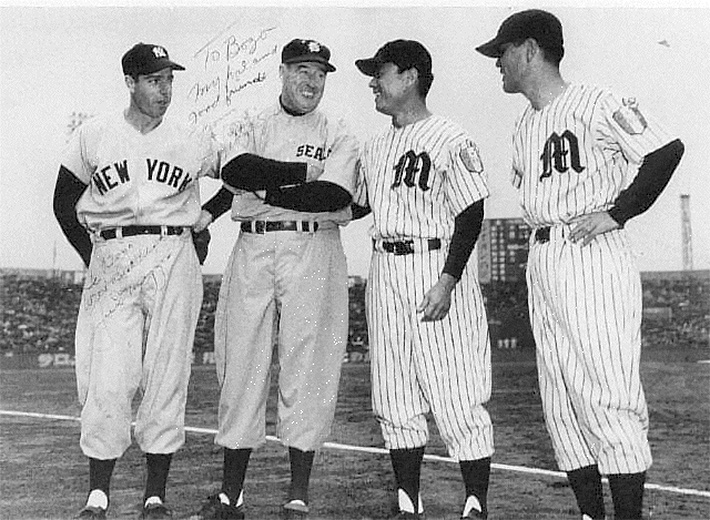

In October of 1949, he took the San Francisco Seals to Japan so everyone could become friends again. Even though he was getting old (already 52 at this point) he pitched in some games. Turns out, people hadn’t forgotten ol’ Lefty O’Doul. Emperor Hirohito and Prince Akihito greeted him. 500,000 people came to watch 10 games. It was, just like every Lefty O’Doul baseball event in Japan, a grand slam.

In Lefty O’Doul style, he kept coming back. In 1950 he and Joe DiMaggio. In 1951, he went big again and led Joe DiMaggio, Dom DiMaggio, Eddie Lopat, Billy Martin, Mel Parnel, Bobby Shantz, Ferris Fain, and Yogi Berra on an All-Star tour of Japan. This was a big deal, to be sure, but the even bigger deal was when the Japanese Pacific League All-Star squad beat O’Doul’s All Stars 3-1. This marks the first time an American professional team lost to a Japanese professional team. Japanese baseball was like that kid whose dad always would beat him in basketball to show him that life wasn’t fair, then one day the kid beats the dad, and so the dad buys his kid a beer. One of those days. To say the least, it was historical for Japanese baseball.

In 1952, O’Doul went to Japan again to help train Japanese baseball teams. Then, in 1953, he joined the New York Giants on a trip to Japan. This would be the first time an entire single team would go to Japan. Even Marilyn Monroe was there (she was married to Joe DiMaggio, so that helped, I suppose). In 1954, O’Doul flipped things around and took a Japanese team on a baseball tour of Australia.

O’Doul would continue to support Japan and their baseball endeavors for years to come, though this is where we have to loop back around to take a look at one particularly revolutionary Japanese baseball player that came about in the years of O’Doul’s return.

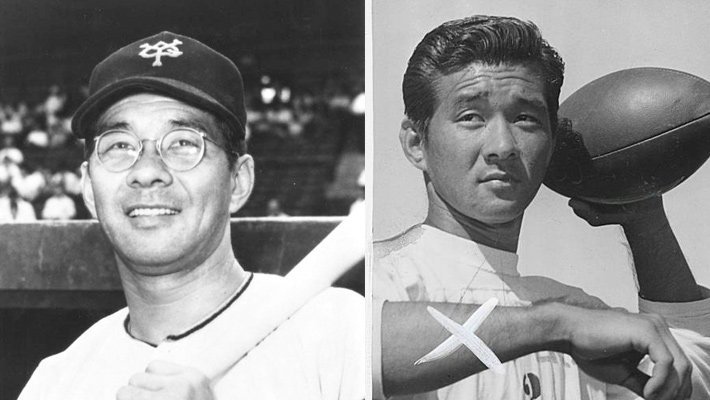

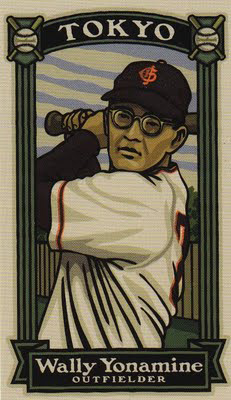

Wally Yonamine, The Jackie Robinson Of Japan (1951)

You may have noticed that the name “Wally” isn’t a Japanese one. That’s right, Wally was American, though still fairly Japanese. He was a nisei (second generation) Japanese American from Hawaii (also super Japanese, though technically a part of America). Although he is most known for his baseball time, he was also the first Asian to play professional American football. Before being injured playing baseball in the off season, he spent a year with the San Francisco 49ers as a running back. He has 19 carries for 74 yards and caught 3 passes for 40 yards.

After injuring himself, he switched to baseball, joining a minor league team. He was lucky enough to have met good ol’ Lefty O’Doul, though, who encouraged him to try out baseball in Japan. Luckily for Japan, he went for it and became the first American to play on a professional Japanese team. In 1951, Wally Yonamine became a Tokyo Giant.

Now you have to understand. It’s not like everyone loved the whole American occupation thing. There were many nationalists (and non-nationalists) who wanted the Americans out, so letting an American play Japanese baseball even though he was a nisei??? That’s just crazy talk. In many ways, he was the Jackie Robinson of Japan, though the divide was more about nationality rather than skin color.

He was still American, though, and the most interesting thing he brought to Japan was that American baseball style. People didn’t know what to do with him. He would run out bunts (unheard of in Japan at the time, apparently). He would do football style rolling blocks to position players blocking the base paths. He would dive in the outfield. He wore those iconic glasses. Basically, he had that American baseball hustle, where an individual could be a star if they stood out in the right ways, and boy did he stand out.

Now, it would be one thing if he turned out really bad, but he dominated the Japanese leagues. He had a .354 rookie season, which won over the fans and his teammates… though one particular player, Tetsuhara Kawakami (the 1951 MVP), particularly didn’t like him. He is disrespectful of Japanese baseball! His parents turned their back on Japan by moving to America! He doesn’t play the “proper” way! This, mixed with the fuel of ultra-nationalism fueled Kawakami’s dislike towards Wally, and the two formed a rivalry which only made them better players. During his career, Wally would win four Japan Series Championships, be the Central League MVP (1957), win seven “Best Nine Awards” in a row, play in eleven All-Star Games, have three batting championships, and then eventually become the manager of the Chuunichi Dragons.

All of these achievements and more got him into the Japanese baseball hall of fame in 1994, though I think it was his style of play that really made an impact on Japanese baseball. Before Wally, there really weren’t any “stars” in Japanese baseball. No nails that stuck up, because that just wasn’t the “Japanese Way.” I think Wally was the spark that set off a new style of play for Japanese baseball. It took a while, but if you compare present day Japanese baseball with Wally’s days, it’s night and day. There still is that very deep rooted team mentality, but there are stars now too. People who stand out. Also, there’s more hustle, people show less “respect” (like walking after bunting or not running into you if you’re in the way) in Japanese baseball as well. It’s a totally different game, and I think we have Wally Yonamine to thank for that.

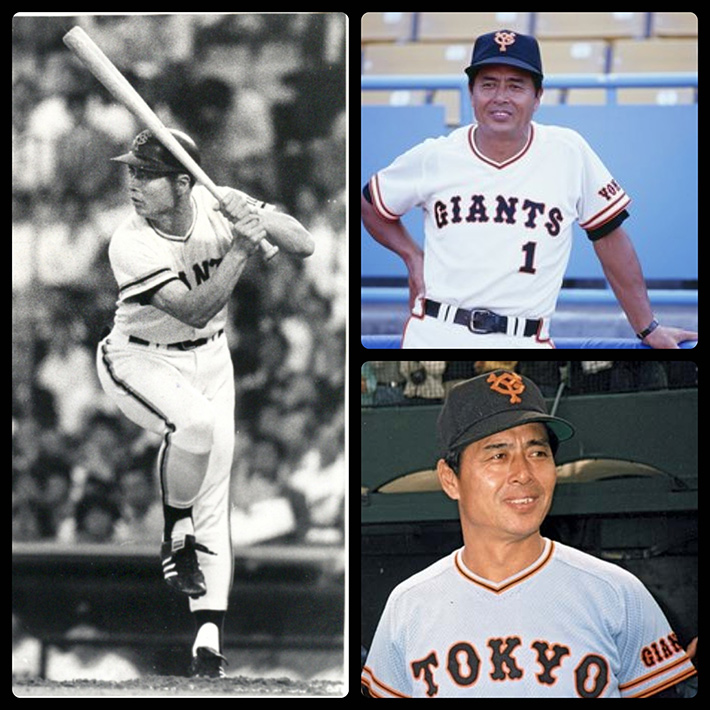

Sadaharu Oh (1959)

Perhaps the greatest Japanese baseball player of all time (at least when it comes to hitting things hard) was Sadaharu Oh. Despite holding the Japanese home runs record (868) he was originally signed with the Yomiuri Giants as a pitcher. He soon got converted to being a first baseman and developed his unique “flamingo” batting style with Hiroshi Arakawa, his hitting instructor. This involved a one-footed stance and swing which supposedly helped him with his balance and ability to hit quite a bit.

It showed, as he went to go to eleven Japan Series Championships as well as win the Central League MVP nine times. If you ask me, that’s too many, and someone else deserves a consolation MVP from time to time. He retired with a .301 batting average, 868 home runs, 2786 hits, and 2170 RBIs. By almost any standards, even in a “lower level” Japanese league, this was pretty good. I have no doubt he would have done quite well in the MLB if he had gone over.

He went on to become a manager (where his home run record had some controversy). Still, he made a huge mark on Japanese baseball. He was one of the first really great Japanese baseball players, showing the world that yes, even Japanese players can hit for power, even if it was in the Japanese League (which had shorter seasons, too). You have to remember, Barry Bonds (the current MLB career home runs leader) has 762 total home runs. Sadaharu Oh hit 868. Even if you consider the differences of the leagues, Sadaharu Oh is still going to hit a lot of home runs no matter where he plays. Even though many people don’t consider this to be “the” home run record, when asked who would break it, Oh seemed to think it would be Alex Rodriguez. “I think the 868 record will be broken. There’s nobody near that mark in Japan, but I think Alex Rodriguez can do it. He has the ability to hit 1,000.”

We’ll see. Once he gets anywhere too close to the record he’ll probably just choke.

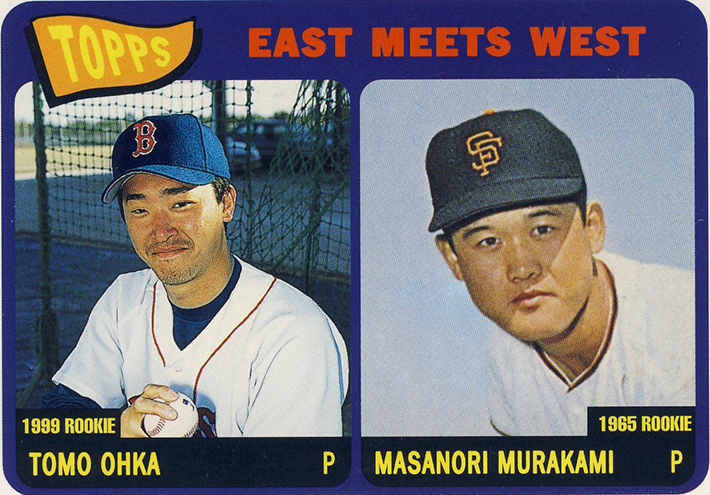

Masanori Murakami Debuts (1964)

While Wally Yonamine was the first American to play baseball in Japan, it wasn’t until 1964 that we see the first Japanese player to play for an American professional team. Most people think that Hideo Nomo of Nomo-Mania fame was the first Japanese player to come over, but Murakami beats him by 31 years.

In high school, he was signed by the Nankai Hawks. His team had won the prestigious Koshien Taikai (a ridiculously popular high school baseball tournament), which probably is what sped up his progress. Turns out, they moved him along a little too quickly, and after pitching just two innings for the Hawks in 1963, they sent him to the San Francisco Giants in the US to train in the minor leagues. It was expected that he’d then come back to Japan after a couple years of this, but he did so well for the Giants that they ended up promoting him to the Majors in 1964.

What made things worse, surprisingly, is that he did quite well. He posted a 1.80 ERA in nine games and fifteen innings pitched, starting things off with eleven scoreless innings. After finishing the 1964 season, the Hawks were “ready” for him to come back. That being said, so were the San Francisco Giants. According to a clause in the contract that sent him to America, the Giants could buy him from the Hawks for $10,000, so that’s what they did. But, Murakami also didn’t want to break his promise to the Hawks, so he signed a contract with the Hawks. Now both teams owned him, and that was obviously a problem.

The two teams came up with an agreement, though. He would pitch the 1965 season with the Giants, then after that he’d go back to the Hawks. He did exactly this, and pitched for seventeen more years in Japan. Poor guy should have just stayed in America. He had this to say about his decision:

If I had returned to the Major Leagues, I would have realized my dream, but I would have betrayed Mr. Tsuruoka. Yet, because I kept my promise to Mr. Tsuruoka, I forever carry this sense of regret.

Possibly because of this situation, it wasn’t for another 31 years that a Japanese player would make the trip to America. Masanori Murakami would be forgotten in the history books, and Japanese baseball wouldn’t make an impact on America again until 1995.

Hideo Nomo (1995)

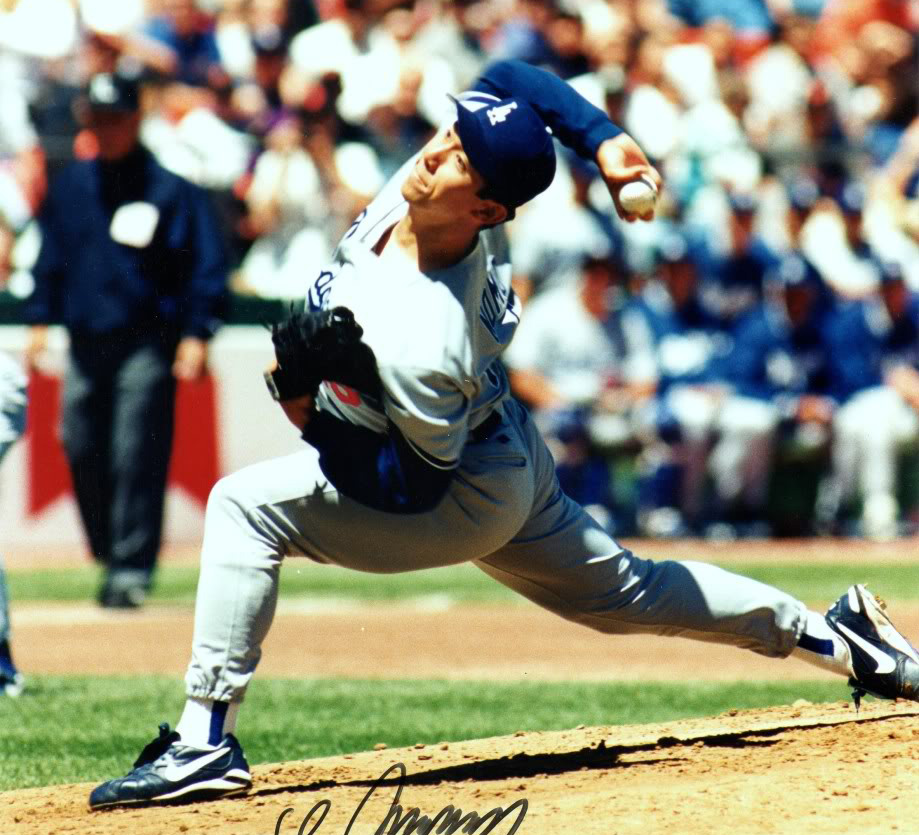

Hideo Nomo is one of the most well known Japanese baseball players to make the trip to America. For one thing, he really stood out with that unique (by American standards) windup. Secondly, he pitched really well, winning the Rookie Of The Year Award in his 1995 debut season. His situation was a bit interesting, though. Normally Japanese teams don’t want their players to move to the MLB. They lose ratings because they lose their best players. Hideo Nomo figured out a loophole in his contract, “retiring” from baseball so that he could sign with the LA Dodgers. If the Buffaloes wouldn’t give him what he wanted (a multi-year contract and an agent).

He made his US debut with the Bakersfield Blaze, a Class A team for the LA Dodgers at the time. He threw 90 pitches and 5 1/3 innings in a 2-1 loss. After spending a month in the minors he was called up to the Major Leagues, partly thanks to a player’s strike, making him the second Japanese League player to come to the majors. The Japanese media went crazy, showing up in huge numbers for his games and making him a star. The games in which he started were even broadcast live in Japan, despite the time difference. His “Tornado Delivery” also became something of a spectacle. If you’re going to stand out, do it in America where they appreciate it more, I suppose.

He had a great career in the MLB, and here are some of the highlights:

- 1995 – Rookie Of the Year Award, just beating out Chipper Jones, leading the league in strikeouts, throwing 11.101 stikeouts per 9 inning (beating the previous franchise record of 10.546), and starting that year’s All-Star Game.

- 1996 – Threw a no-hitter on September 17 in Coor’s Field, a stadium notorious for being a hitter’s park. Also had his own Nike sneaker, the Air Max Nomo.

- 1997 – Greatest honor of them all, appeared in a Segata Sanshiro commercial.

- 1997 – Joined Dwight Gooden as the only other pitcher to strike out at least 200 batters in each of his first three seasons.

- 2001 – Playing for the Boston Red Sox, he throws his second no-hitter, making him one of the few pitchers to have thrown a no-no in both leagues. He also leads the league in strikeouts again.

- 2002 – Returns to the Dodgers where he pitches well again.

- 2003 – Begins showing signs of his age :(

- 2008 – Nomo retires from Major League Baseball.

Nomo and his Nomo-mania were a big deal in both Japan and America. After the Japan Baseball League lost Nomo to the MLB, the two leagues came up with a “posting” solution, where MLB teams could make bids to talk to Japanese players, so that way if they lost the player they’d get compensated. This posting system would get used a lot in the coming years. Nomo really opened the doors for Japanese players to come to the MLB, and a good number of players have followed since.

Ichiro (2001)

Being the biggest Mariner’s Fan in the world, it pains me to write about Ichiro, just a little bit. I could go into the goods and bads of him being a Yankee right now, but let’s not focus on that. Let’s focus on his contribution to position players coming to America, because before Ichiro, only pitchers would make the jump from Japan to the MLB.

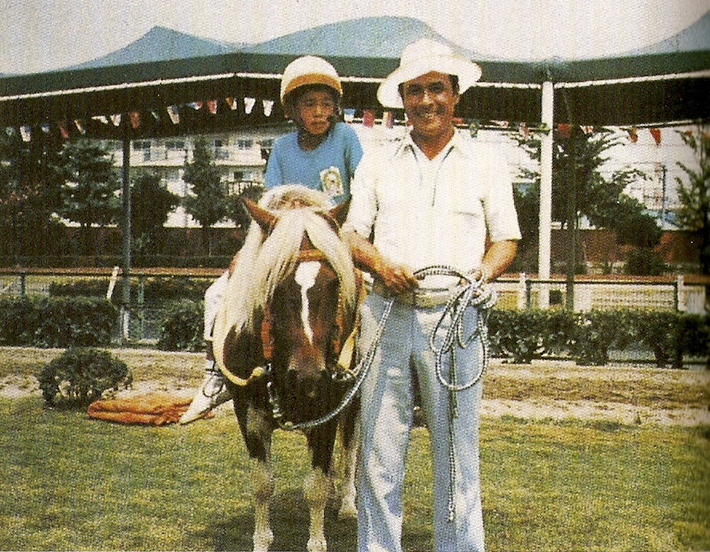

Before becoming the MLB’s most well-known Japanese player, Ichiro was a mere child with a father that was really into training him. After joining a baseball team at the age of seven, he asked his father to help him to get better. They began a regiment that included throwing 50 pitches, fielding 50 infield balls, fielding 50 outfield balls, and hitting 500 pitches (250 from his father, 250 from the machine). By age 12, he dedicated himself to pursue a career in baseball. In high school, his father told the coach to never praise Ichiro because he needed to be spiritually strong. Joining Nagoya’s Aikodai Meden High School, he was used as a pitcher due to his strong arm (which we’ve all seen in the majors). He batted .505 in high school with 19 home runs. Other strange training regimens that Ichiro did included hurling car tires, hitting wiffle balls with a heavy shovel, and practicing in the batting cages by getting closer and closer to where the ball shoots out the hole. To say the least, he worked really, really hard, much of it due to the training (which bordered on hazing, according to Ichiro) of his father. Anyways, it worked out.

In 1992 at the age of 18, he made his Pacific League debut, though had to spend much of his first two seasons in the Japanese minors. The manager at the time didn’t like his unorthodox swing. Obviously, the “nail that sticks up” mentality was still prevalent in Japanese baseball, even in the 90s. Two years later a new manager was hired, and Ichiro then got playing time every day. His “pendulum” swing proved effective, and he broke the then Japanese single-season record with 210 hits in a season. He hit .385, had 13 home runs, and stole 29 bases. This would be the first of three straight MVP awards.

As if the nail that was Ichiro didn’t stick up enough, in 1994 they changed his jersey to read “Ichiro” instead of “Suzuki,” which is the most common last name in Japan. It was the management’s idea, not Ichiro’s (he was embarrassed by it, apparently), though it ended up catching on and helped him to achieve a greater fame.

It wouldn’t be until 1998, though, that he would see some major league action. In a seven-game exhibition between Japanese and American All-Stars, Ichiro batted .380 and collected seven stolen bases. He was now officially on people’s radars.

Of course, in 2001 he joined the Seattle Mariners after they paid a $13 million posting fee, and then signed him to a three year $14 million contract. Apparently at first he didn’t feel too good about wearing ex-Mariner Randy Johnson’s number (51), so he sent a message to Johnson promising to not bring shame on the uniform. He turned out to do pretty well, batting .350 with 56 stoeln bases, making it to the first of ten All-Star games, winning Rookie Of The Year, and the AL MVP award. Pretty big stuff for a short guy from Japan who’s never played a “grueling” American 162 game season.

Ichiro went on to many other successes as well (and still plays for the Yankees to this day). Some highlights include:

- Ten All-Star Games (2001-2009)

- Rookie Of the Year Award (2001)

- 10-time Gold Glove winner.

- 200 hits in 10 consecutive seasons.

- 256 hits in one season, a Major League record.

- “The Throw”

People stopped running on Ichiro after this fateful day. Actually, people didn’t stop, but they were punished for their mistakes. With Ichiro becoming such a huge star in Seattle as well as the world, other Japanese players would make the leap across the pond. Some have done well, some have not. Let’s take a look at what we’ve got.

The Japanese Player Flood

All in all, 52 Japanese League players have come to the MLB, most of them arriving after Ichiro. While there are this many players, only some of them had seasons of great success. They include:

- Ichiro (10 All Star Games)

- Kazuhiro Sasaki (2 All Star Games)

- Hideki Matsui (2 All Star Games)

- Hideo Nomo (1 All Star Game)

- Shigetoshi Hasegawa (1 All Star Game)

- Hideki Okajima (1 All Star Game)

- Takashi Saito (1 All Star Game)

- Kosuke Fukudome (1 All Star Game)

- Yu Darvish (1 All Star Game)

Of course, more will come, and with the higher level that is the Major Leagues, better and better Japanese baseball players will come out of Japan too. If all the good players don’t just come over to the MLB, Japan’s teams may become comparable too, though we’ll have to wait and see on that one.

Awards And Notables

According to Wikipedia, here are the awards that have been given to Japanese League players in the MLB.

- Most Valuable Player Award: Ichiro Suzuki, 2001 AL

- Rookie of the Year: Hideo Nomo, 1995 NL; Kazuhiro Sasaki, 2000 AL; Ichiro Suzuki, 2001 AL

- Gold Glove Award: Ichiro Suzuki, 10 times, 2001–2010 AL OF

- Silver Slugger Award: Ichiro Suzuki, 3 times, 2001, 2007, 2009

- All-Star Game MVP: Ichiro Suzuki, 2007

- World Series MVP: Hideki Matsui, 2009

- Player of the Month: Ichiro Suzuki, August 2004 AL; Hideki Matsui, July 2007 AL

- Pitcher of the Month: Hideo Nomo, twice, June 1995 & September 1996 NL; Hideki Irabu, twice, May 1998 & July 1999 AL

- Rookie of the Month: Ichiro Suzuki, 5 times, April, May, June, August, September 2001 AL; Kazuhisa Ishii, April 2002 NL; Hideki Matsui, June 2003 AL; Hideki Okajima, April 2007 AL; Yu Darvish, April 2012 AL

- Player of the Week: Hideki Matsui, 4 times, June 23–29, 2003, May 24–30, 2004, June 14–20, 2005, July 18–24, 2011 AL; Ichiro Suzuki, 4 times, August 2–8, 2004, May 29-June 4, 2006, September 20–26, 2010, September 17-23, 2012 AL

- MLB Players Association Outstanding Player of the Year Award: Ichiro Suzuki, 2004 AL

- MLB Players Association Outstanding Rookie of the Year Award: Ichiro Suzuki, 2001 AL

- Sporting News Rookie Player of the Year Award: Ichiro Suzuki, 2001 AL

- Sporting News Rookie Pitcher of the Year Award: Hideo Nomo, 1995 NL, Kazuhiro Sasaki, 2000 AL

- MLB.com Defensive Player of the Year Award: Ichiro Suzuki, 2005

- MLB.com Setup Man of the Year Award: Hideki Okajima, 2007

There are a lot of names that get repeated (*cough* Ichiro *cough*), though this should give you an idea of some of the talent that’s coming out of Japan.

So, that’s the history of Japanese baseball, from the early days to present day. I wonder what the future holds for Japan. I suppose you’ll just have to wait and see. When it comes to Japanese baseball, it’s like they’re on first base, getting ready to steal second. There’s a lot more life yet, and I’m looking forward to seeing it spring forth from Ichiro’s loins.

Who’s your favorite modern-day Japanese baseball player? If you tell me Munenori Kawasaki maybe I’ll do the Mune dance for you.