It's really tough being a vegetarian in Japan. That being said, I'm not a vegetarian around 25% of the time (BACON), so I can't really speak from experience, but it's so obvious. Unless you're willing to eat fish, being a vegetarian is a huge pain in the neck.

There is hope for vegetarians in Japan, though, and that comes from a type of cooking known as shojin ryori 精進料理 which I guess sort of translates to "devotion/self-discipline cooking." The idea is that this type of food will put you in the best frame of mind to understand Buddha's teachings.

Over the course of several articles, I'm going to go over shojin ryori. In fact, I'll even be eating and preparing shojin ryori food for your pleasure (I'm so bad at cooking) and education over the next few weeks. But first, we need to learn more about the philosophy behind it. Let's find out.

Why Shojin Ryori?

Besides being the most delicious vegetarian food on the planet (by a lot, mind you), shojin ryori is incredibly good for you. Eating like this, while difficult, is going to make you more energetic, feel better, and probably prevent 50 different kinds of cancer (while only giving you 3 or 4, nice trade). You do have to consider the salt intake that comes with this type of eating, but in terms of trade-offs shojin ryori is a very healthy option (you stop your scoffing, raw food vegans, or Buddha will smite you with his giant metal foot).

Really, though, when foods are fresh they tend to be healthy, and shojin ryori is (traditionally) all about the freshness of foods. While you and I just walk down to the grocery store to buy apples and naners any time of the year, Buddhist monks practicing shojin ryori harvest only seasonal fruits and vegetables even though the nearest Lawson's is probably only three blocks away. But convenience isn't the point! The point is that local seasonal foods bring you in flow with nature. Not only that, but the foods that grow in different seasons are supposedly the foods your body needs during that season. Mari Fujii who wrote "The Enlightened Kitchen" says it best:

The slight bitterness of spring buds and shoots […] is said to remove the fat the body accumulates during the winter. Summer vegetables from the melon family, such as tomatoes, eggplants and cucumbers, have a cooling effect on the body. Fall provides and abundant harvest of sweet potatoes, yams, pumpkins and fruit, which revive tired bodies after the heat of summer. In winter, a variety of root vegetables, such as daikon radish, turnip and lotus root, provide warmth and sustenance.

The thing is, these kinds of foods are also extremely healthy for you. You won't be digging up any McRibs (even though they're seasonal too) in the ground around any Buddhist temple. Besides, McRibs contain too much sentient animal meat, and because Buddhists believe that all sentient life can achieve Buddhahood, they don't eat said sentient life. So, shojin ryori is going to be plant based (includes sea plants). As shojin ryori chef Keizo Kobayashi says:

The abstention of eating flesh (meat, fish, fowl, etc.) and the limiting oneself to a vegetarian diet is a discipline of "right effort." it is based on the precept of non-killing, for all sentient (living) beings have the potentiality of Buddha-hood. We realize that it is not possible to survive without sacrifice of living beings, for plant life is included, also. Through this practice, we strive to develop true awareness, reverence and appreciation of the interdependency, or oneness of all life.

So, it's not just being vegetarian to be vegetarian. It's really more about the state of mind you're put in. You have to think about what you eat. You have to think about where the food comes from (and often get it yourself). The food as well as the preparation of the food prepares you for Buddha's teaching. Not only does the food make you feel better, but it also makes you think.

Preparing For A Month Of Shojin Cooking

It wouldn't be particularly easy for me to spend the month cooking seasonally fresh vegetables, not to mention that the things that grow in Japan don't necessarily grow here, so I'm going to rely on my local Asian grocery store to bail me out. I went through a couple of shojin ryori recipe books before heading to the store, writing down all the ingredients. I then went through to find the most common fresh ingredients (80/20 rule, baby), the ingredients I could buy once and use for a long time (kombu, sesame seeds, etc), and the fresh ingredients that only appear occasionally. I then went shopping, buying a ton of ingredients for around $100. It'll come out to be quite cheap, all in all.

Over the last few weeks I attempted to prepare several dishes, starting pretty simple. I focused on ingredient management and the pairing of dishes, since shojin ryori tends to be comprised of several separate pieces. And I'd like to think I got better through trial and error.

Out of all the types of food I've had in Japan, I wouldn't say this is the thing that I like eating the best (though it's way, way up there). It is however the type of food I'm most fascinated with. Making something this delicious without meat or dipping sauces is quite remarkable. If I was to go all-in vegetarian, this would be the kind of food I'd eat. While it's way more difficult to prepare than most vegetarian dishes, it is by far the best tasting.

Shojin Ryori Ingredients

Over the last week I’ve been cooking various shojin ryori dishes so I’m starting to feel comfortable about what is used and what isn’t used, so, I’m not going to tell you every ingredient ever that you could buy. If I did that this list would be quite a bit longer. Instead, I’ll attempt to use the 80/20 rule and narrow this list down to the ingredients that get used 80% of the time, so to speak. Basically, these are the ingredients you’re going to want on hand if you plan to start eating like a Buddhist monk anytime soon.

Let’s go over each ingredient. I’ll do a bit of explanation if explanation is necessary (for example, I bet you know what a carrot is already). I’ll also break them up into sections based on where you’ll store them and how long they’ll last, giving you a better idea of what you can have on hand for a long, long time, and what you should get and use right away.

Fresh Produce

These ingredients will be found in your produce section (or, hopefully they will). If you’re particularly tricky, you can grow a lot of these yourself, too. Many of these are actually very easy to grow, and even someone as terrible at growing as me can manage some of these. Plus, you’ll be getting yourself into the shojin ryori spirit: Fresh and seasonal!

Daikon

Daikon is great. It’s a root, and it soaks up all kinds of awesome flavors. Oh, and did I mention it’s excellent for your health? These guys tend to be pretty huge and pretty cheap as well. That’s a lot of veggie for your buck, right there. You can use them in almost anything, though I think they go particularly well with soups, stews, and pickles. You’ll also find them used as a garnish quite often as well.

Ginger Root

While shojin ryori shies from really strong tastes (like onions, for example), ginger does have its place in the shojin ryori kingdom. It’s used as a garnish and just adds a little bit of taste while not dominating. You won’t see any / many overly gingery things in shojin ryori, though you will see ginger quite a bit. It goes great with tofu, for example, and it will last for a really long time in your fridge.

Pro Tip: Use a spoon to scrape the skin off. It’s way easier than a knife or peeler, and leaves you with a lot more ginger.

Gobo

This could be slightly difficult to find depending on where you live, though I’m seeing it more and more in regular grocery stores. Gobo (or Burdock Root) is used in a lot of stews and soups in shojin ryori. It’s a ridiculously long root and pretty tough. You’ll want to be sure to peel the skin off before eating it most of the time. Often, you’ll want to parboil it too (boil it a bit before cooking it with everything else). Gobo has a sort of earthy, mild taste to it. It definitely has a warming effect when you eat it, as well, making it great in stews and soups.

Shitake Mushrooms

Shitake mushroom are probably something you’ve seen and heard of before. They’re probably the most important mushroom to get when it comes to shojin ryori. There are other mushrooms as well that would be nice to have, and I’ll include them below, but if you can only get one, get this, because shitake mushrooms are used in a lot of recipes. If you can’t find fresh shitake mushrooms (or they’re too expensive), you can also get them dried. In fact, either way I’m going to recommend getting dried shitake mushrooms in addition to fresh ones. If you can manage getting both then you get double the mushroom fun.

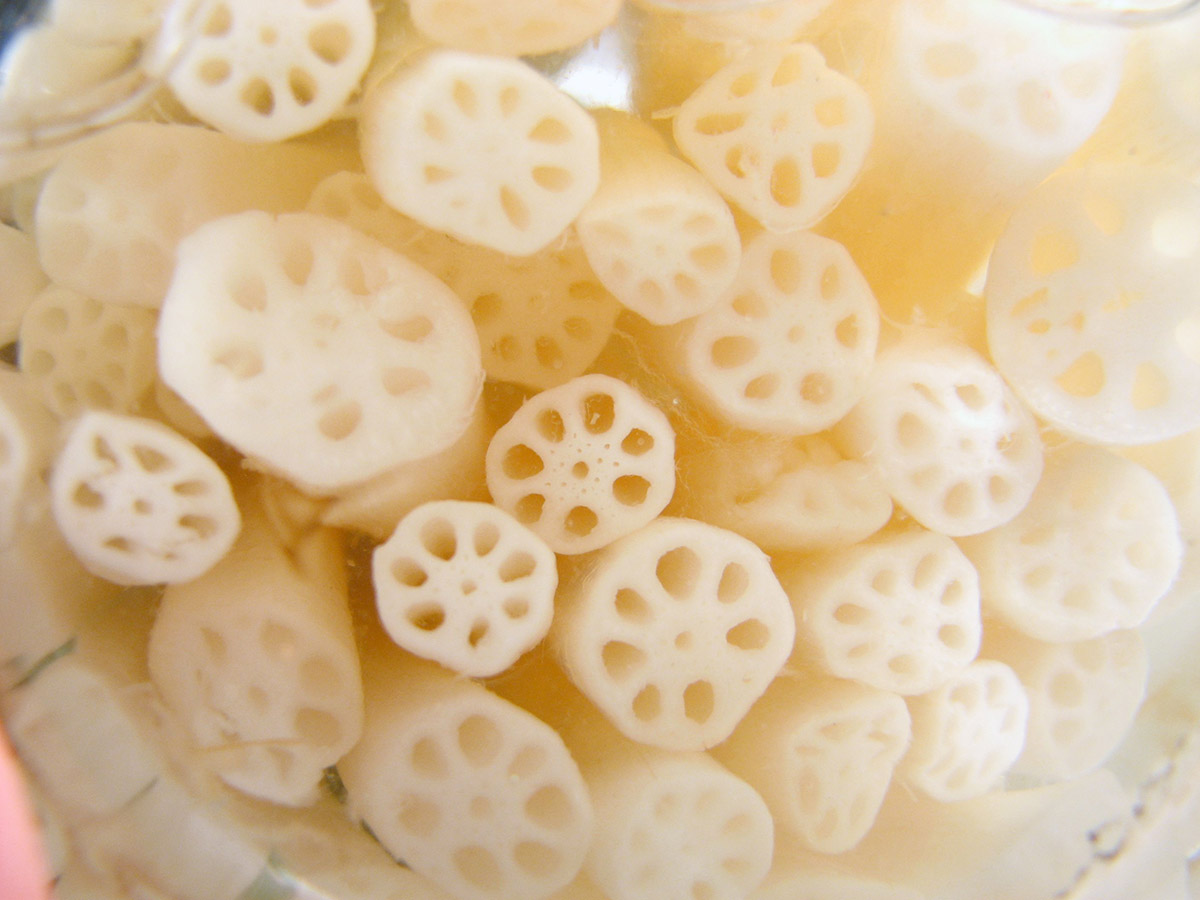

Lotus Root

Lotus Root is a large eggish shaped root that looks kind of terrifying on the outside. Then, when you shave the skin off and cut into it you get a nice, crisp, clean looking thing (as seen in the image above) that tastes oh-so-delicious. Lotus root adds a bit of fresh crispness to any dish you add it to. In stews, you definitely get pleasure from the texture of it. It’s kind of like an apple without the apple taste, and definitely a staple of the shojin ryori diet. Plus, as long as you don’t cut them, they’ll last a pretty good amount of time in your fridge.

Pro Tip: If you have any left over cut lotus root, store it in some water with a bit of rice vinegar. This will prevent it from turning brown.

Carrots

Carrots are awesome. I think you know what carrots are, right? Orange? Long? Delicious? These are going to go in stews, pickles, tempura, and more. Plus, they last forever in the fridge, so they’re always worth having.

Potatoes

Potatoes are another thing you probably know all about. I’d recommend, in general, getting those white or yellow potatoes. Yukon Golds are pretty good. Of course, there are other kinds of Japanese potatoes as well that might be worth getting, but those are harder to find for most people and good in more specific situations. Regular old potatoes are in plenty of recipes and turn out really, really tasty. Grab a bagfull and hold onto them. They last a while and will make good side dishes to go along with anything you make.

Japanese Eggplant

Japanese eggplants are a little different from Western eggplants. They’re smaller, straighter, and have less bitterness. You also don’t have to peel them, either, because of their supple thin skin. Japanese eggplant is the centerpiece of many shojin ryori dishes, so you won’t go too long without using them.

Optional Fresh Produce

Now let’s get into the produce that isn’t totally necessary but “nice to have.” There are some good dishes for all of these things, though I wouldn’t necessarily call them staples (though I can see where some people would disagree with a few of my categorizations).

Kabocha Pumpkin

Kabocha pumpkins are a Japanese pumpkin. Warning: They are a pain to cut, so be careful! If you have a choice, the Kikuza or Kurokawa varieties are best, but most likely you’re just going to see something that says “kabocha” at your grocery store (if you see anything at all). These are great steamed, stuffed, tempura’d, and more. You get a meaty texture without any meat and they have a very unique taste. I think a lot of people either hate it or love it, so hopefully you’re on the “love it” side! If you see a kabocha pumpkin, just grab one and hold onto it. They’ll last quite a while.

Yamaimo and Nagaimo

These are two Japanese potato varieties that are used in a decent number of recipes. These will probably be tough to find if you don’t have an Asian produce mart, and sometimes turn out to be pretty expensive. These are on the “nice to have” list, but totally not necessary. I probably won’t show you any recipes that use either of these potatoes, though I do have some in my fridge so I’ll definitely be eating them. Maybe a meal or two will change my mind :)

Shiso Leaves

It hurts me to put these on the “optional” list due to my love of shiso, and while I personally would never make them optional, I don’t think this is something a lot of you will be able to find. That being said, it’s very easy to grow in any temperate climate. The plants outside on my patio won’t stop growing and I can’t eat the fresh shiso leaves fast enough. These are a great addition to a lot of stuffings and also make great garnishes. Also, they’re great to just pop in your mouth to chew. I love you, shiso

Okra

Okra is in a few things and is nice to have. I would say don’t worry about it unless it’s seasonal, fresh, and delicious. Otherwise, it’s best not to force okra.

Japanese Cucumbers

Japanese cucumbers are a bit different from other cucumbers (though quite similar to English cucumbers, so substitute with those!). They have a thin skin and edible seeds, meaning you don’t have to do any work and they’ll taste good. These are going to be good for side dishes and pickles. If you’re going for a whole course, then you’ll want to have Japanese cucumbers on your ingredients list. If you’re just going for main dishes, Japanese cucumbers fall to the “nice to have” list. That being said, they’re really nice to have, and add a freshness to every meal.

Enoki, Shimeji, and Button Mushrooms

These mushroom varieties are nice to have along with shitake. Enoki is going to be the easiest and cheapest to find so start with that (plus, enoki really matches with a lot of things). The other two (Shimeji and Button) become slightly more optional. These mushrooms will make great toppings and add a lot to a lot of dishes. You can’t go wrong with mushrooms!

Lemons

If you have a few lemons on hand you can make your own ponzu. Ponzu made fresh is way better than ponzu from the bottle. If you don’t want to carry lemons, get ponzu in the bottle, but I’m warning you, it’s not as good.

Lasts Forever:

This section is full of things that will last forever (or a really long time). Many of these are dried. Many of these are liquids. All of these belong in your pantry.

Dried kombu

This is probably the most important ingredient. Without it, you can’t make your kombu stock, and kombu stock is used with nearly everything. That being said, you can substitute this with “vegetarian dashi” though it won’t be as good, I think. Dried kombu not only makes your stock, but you can eat it too. It will be in some soup and stew recipes that use the stock you sucked from its once dry, lifeless corpse. If you’re really lucky you can get it fresh. Really it’s just kelp from the ocean and almost nobody in the West thinks to eat it (kind of like fish collars, you guys are missing out!).

Pro Tip: Wipe your dried kombu with a damp paper towel. It will get the sweet white powder that develops on the top, but not get too much of it. You don’t want to get rid of it all, so don’t wash it (but you don’t necessarily want it all there, either). Wipe!

Sesame Oil

Get some sesame oil. When it comes to oils, I think sesame has the most flavor. Some dishes just don’t taste right with out it. I like roasted sesame oil, personally. It has a lot more flavor, if you’re into that sort of thing. If you can buy this at an Asian market it will be 10x cheaper.

Sesame Seeds

Sesames seeds don’t have quite the taste as sesame oil, but they are used in a lot of dishes. Get a bag or container full of them and they’ll last you quite a while.

Pro Tip: Roast them in a pan first if you want them to be more flavorful.

Rice Vinegar

Grab some of this while you’re in the soy sauce aisle. Like all of these sauces, buy it at an Asian market for 400% savings.

Mirin & Saké

Also grab some of this. Mirin is basically sweet saké, I think, and is often one part of a great marinade or sauce. While you’re at it grab some cheap regular saké to cook with. Saké is part two of the “good marinade or sauce” train. The third part is:

Shoyu (Soy Sauce)

I’m going to call it shoyu from now on, so get used to it. Shoyu is in pretty much everything. Don’t get a dinky table-sized shoyu (unless you want something to pour shoyu out of). Get a half gallon or gallon jug (maybe not the 5-gallon barrel, though). If you cook enough shojin ryori you’ll go through it like it’s nothing. Plus, you save a ton of money. Also, don’t buy the low sodium stuff. You’re already losing the taste of fish and meat in shojin ryori, so you need that extra 30% sodium, in my opinion.

Dried Wakame

This isn’t used as much as dried kombu though it’s nice to have. If you make miso soup (like, real miso soup, none of that instant stuff) you’re going to want some dried wakame to put in it. It’s used in a few other recipes as well, so it’s nice to have. Plus, wakame is a cancer murderer.

Dried Shitake

Dried shitake is sometimes better than fresh shitake. You can use it to make shitake stock or make kombu stock better have a little more umami. Plus, it lasts forever whereas fresh shitake will go bad. It’s a nice backup to have in case you forgot to get regular shitake. It’s also less expensive by quite a bit depending on where you’re buying your shitake from.

Rice

You can’t eat something Japanese without rice. Although many shojin ryori chefs will have other non-white grains in their rice, for the simplicity of this series I’m sticking with white rice though there are some good rice recipes to be had. I’d recommend buying slightly more expensive rice (don’t get the really cheap stuff, it tastes cheap). I also hear rice from the South East United States has higher rates of arsenic in the rice, so I usually avoid rice from there. Whatever you get, it’s going to go with every single dish you make. Just don’t overdo it on the white rice or you’ll get the diabeetus.

Flour, Sugar, Baking Soda, Salt…

I’m going to assume you already have a lot of these, but just in case… you know? Buddhist monks use flour too, sometimes, though it’s rarely for birthday cakes.

Sansho Pepper

I’m going to put this in the dry goods area just because that’s probably how you’ll find it if you find it at all. First of all, it’s not actually a pepper. It comes from ground up sansho (prickly ash) berries. It has a sort of earthy tangy taste to it, and is responsible for some unique flavors in shojin ryori. If you find this pre-ground, then that’s fine. If you can find the berries and grind them, even better. If you can grow this little guy yourself (not too hard to do, I hear), harvest the berries, dry them,then grind them, then double-thumbs up to you. If you can’t get your hands on this it won’t be the end of the world, though everything’s better with sansho, as they say.

Refrigerated & Processed

Let’s move onto the last section. These are things that will be in your fridge. They are processed for you so you don’t have to go out and make your own miso from scratch, which is pretty nice. All of these ingredients are pretty important, and quite a few last for a long time.

Konyaku

Konyaku usually comes in blocks in plastic packaging (like the photo above). It’s made from the corm of the konjac plant (thus konyaku) though for some reason most people think it’s made from yams. Strangely, konyaku is nearly zero-calorie (doesn’t taste like it!) because it’s mostly water. That being said, it goes well in a lot of soups and stews in shojin ryori dishes and is used quite often. Grab yourself a few packages of konyaku and you’ll be using them soon.

Red Miso

The first kind of miso. Red miso is going to have a stronger taste because it gets fermented for longer and has a higher percentage of soybeans. When it comes to miso soup, I prefer red miso. It’s good for having a strong miso flavoring, if that makes any sense.

White Miso

The second kind of miso. White miso has a milder taste and is quite different from red miso (why it’s good to have both). It’s a bit sweet and is used in various sauces and dressings. This is good to have when you need a softer miso taste.

Tofu

In terms of processed foods, tofu is going to be the most important thing on the list. It’s used in almost everything and is the source of protein. If you’re not having tofu somewhere it’s not going to feel like shojin ryori. There are many types of tofu you can buy too. For shojin ryori, just get some silken and some firm. You’ll find recipes that require one or the other, and both are pretty common. Don’t buy medium. Medium is for people who want everything but then end up getting nothing.

Umeboshi

Umemboshi may be on your “nice to have” list, but it’s on my “need to have” list. I think I’m an addict. Like natto (below) a lot of people aren’t a fan of umeboshi. I like people like that, because then I get to eat their’s. Umeboshi is known as “pickled plum” in English. When you spend more it generally tastes better, but you should find out if you like it first. Umeboshi makes for a nice little (salty) dessert at the end of your shojin ryori meal. It also can be mushed up and used in sauces to make things a little tastier. Personally, I prefer seeing how many I can fit in my mouth at once, but that’s just me. Perhaps next year in the spring I’ll hand craft another batch of umeboshi myself and do a write-up so you can do it too. Truly, homemade umeboshi are the best umeboshi.

Natto

Last but not least is Natto. Personally, I’m not a fan. Natto is made from fermented soy beans and tastes… different. I think I heard somewhere that half of Japan hates the stuff and the other half loves it. Seems about right. It tastes better when you add a few other ingredients to the mix, though. Natto isn’t going to be something you use a ton, though you can choose to use it as much as you want. It’s easy to prepare and ridiculously healthy for you… almost too healthy. I’m suspicious.

Putting It All Together

Looking at this giant list of ingredients may seem a little overwhelming, but hopefully I was able to simplify it for you a bit. There are, of course, a ton more ingredients you could be using that I didn’t include on this list, just because it would be too much. If you have these ingredients, you can make most shojin ryori things. After that, it’s up to you to grab what you need on a per recipe basis.

So, these are the ingredients you’ll need. Now I’m going to go over putting some of these ingredients to use, covering the staples: stock, rice, sauce, and so on. If you don’t make good staples you can’t make good food. In shojin ryori, these staples ore doubly important, just because you have to make something delicious tasting without meat (oh meat, you make cooking so much easier!). I’ve been experimenting with a lot of different stock strategies, trying to come up with the perfect combinations.

Prepping Your Foundation

Now we’re going to go into the actual making bits, though we’re going to stick with the foundation. Being vegetarian, shojin ryori has some pretty delicate tastes, meaning these foundations are going to be extremely important if you want to make good tasting shojin ryori food.

So what are the foundations? In my mind, they are the stocks, the rice, and the sauces. The sauces are extremely easy and don’t take much effort. The rice, while just rice, is very important to get right. Rice really pulls all the dishes together and serves as a sort of “reset” between bites. Then finally there’s the stocks, which are probably in 30% of the shojin ryori recipes out there. This means that each meal will probably consist of some kind of stock. Because stocks are the hardest (in my opinion), we’re going to start with that and work our way down.

Dashi (Stocks)

When it comes down to it, dashi = umami. Umami was discovered by Dr. Kikunae Ikeda who figured out that umami (the fifth basic taste, apparently) comes from the amino acid glutamate. Now, here we’re going to learn about the traditional Japanese dashi stock, which comes from kombu, though it’s good to know that the term “dashi” refers to all kinds of Japanese stocks, the most common of which uses fish flakes as well as kombu for the flavor. Dashi is pretty much the main reason why it’s hard to be vegetarian in Japan. Everything is full of dashi that has been made with fish (it’s delicious, by the way).

Here we’re going to learn about vegetarian shojin ryori dashi, though. When making dashi, your goal is to add this umami taste to your food. Now, because umami comes from glutamates, one thing we can do is look at how many glutamates different ingredients have.

- Kombu: 2240

- Wakame: 9

- Tomato: 246

- Shoyu (Soy Sauce): 782

(These numbers are milligrams of glutamates per 100g)

Another thing you can get umami from is guanylate, which can be found in various dried vegetables. By far, the winner in this realm is shitake mushrooms, which have 150 mg of guanylate per 100g. This will come up again in the stocks section so take note.

But, notice something out of place in the list above? That’s right, tomatoes have quite a bit of umami, at least compared to most non-kombu ingredients. Ever wonder why your pizzas and spaghetti sauces tasted so good? That’s right, umami. Try to see if you can detect the mystery flavor the next time you eat something with lots of tomatoes.

Kombu Stock

Kombu stock can be made from dried kombu. Usually you can find this in a regular grocery store, though it really depends. One thing to make certain of is that you have dried kombu. Not just any seaweed will do. For example, wakame has almost no umami magic in it (see the umami-magic list above).

There are a ton of kombu stock recipes out there and I’ve tried them all. This is the best one, and I’ll tell you why afterwards:

Ingredients:

- 6×6 inches worth of dried kombu. Wipe it with a damp paper towel.

- 1 quart of cold / room temperature water

Nice and simple, right? You’d think that it would be hard to mess up, but you would be wrong. Follow closely now. First, fill up a glass container (glass is preferred just because vegetable broths soak up outside flavors very easily) with 1 quart of water. Then, put your dried kombu in it. Cover this container with something and then wait for 5-6 hours. When that amount of time has passed, put the kombu into a sealed container. You’ll probably end up using it in something or another. If it starts growing a white filmy thing, throw it away. This is not good.

So how is it possible to mess up something like this? Well, there are many recipes that do it the wrong way. Here’s how they screw up (don’t do these things).

-

They have you warm up the water to speed up the process. If you have to do this in a pinch, it will make your dashi more quickly, but it will also taste worse. This is because the enzymes that break down the umami and allow the flavors to melt together work best at lower temperatures. When you heat things up they break apart faster for a while, but then they will become inactive. Just make sure you start your dashi earlier.

-

They don’t have you put in enough dried kombu. The richer you want your dashi, the more kombu you should add. I wrote 6×6 above but I usually put a bit more than that. Probably around 8×8 inches worth of dried kombu? They don’t have you cover the container, which means other smells and tastes can sneak their way in. You want your dashi to be as pure as possible for a better taste.

-

The main things here are to make sure you start early so you don’t have to rush and thus compromise the taste of everything your dashi goes in. If you follow these simple rules your dashi will be splendid!

Shitake Stock

Shitake stock doesn’t get used nearly as much as kombu stock, but it’s an important one to add. It’s about as easy as kombu stock, too.

Ingredients:

- ~8 dried shitake mushrooms

- 2-3 cups warm water

- 2-3 cups room temperature water

There are a lot of different opinions on this, but you have to remember: shojin ryori is full of delicate flavors. So, we’re going to make a delicate stock. First, put your dried mushrooms in the warm water. This is the get all the bitterness and crap out of your shitake mushrooms. After 15 minutes, drain the water and refill with room temperature water. This is going to be your stock. When the mushrooms are nice and tender (you like touching those mushrooms, don’t you pervert?) you can remove the mushrooms for use in some other recipe and then keep the shitake mushroom stock for whatever you want.

Kombu + Shitake Mushroom Stock

Lastly, here’s a little hint. For umami explosion, you can make stocks that contain both kombu and shitake. That means you’re getting tons of glutamates and guanylates. That’s double the umami right there for you. If you do this you can expect a richer broth. I use this in some soups and stews to add a little extra flavor when I’m feeling feisty.

Making Rice

Rice is like The Dude’s rug, it really ties the dishes together. When eating Japanese food, you tend to have many different things to eat from. Each dish will have a different texture or taste, allowing you to have the most satisfaction possible while eating your meal. Instead of just eating all your rice at once, for example, you’d come back to it every once in a while to sort of reset your mouth before moving on to the other taste. Suffice to say, it’s important.

Buying Rice

The difference between good rice and bad rice is pretty big, at least when you’ve had good rice before. With good rice, it’s almost as if you can taste and feel each individual grain in your mouth. With bad rice it’s all mushy and doesn’t have a distinct flavor. Buy good rice and you’ll thank yourself later (though your bank account may not). Look for rice that’s been nicely polished, too, it helps with the taste.

Oh, and in case it goes without saying, get Japanese style short-grain rice.

Preparing And Cooking Your Rice

Although your rice bag will probably give you a better method for making the particular rice you’ve bought, let’s go over some basic things here. For this particular “recipe” I’m just going to go with one cup of rice. Double or triple it as needed. Also, I’m going to assume you don’t have a rice cooker. Rice cookers are like magic and make delicious rice. The one I have makes perfect rice (and plays music, too).

-

Put the rice in a separate bowl. Rinse it out, drain, rinse it out, drain, rinse it out, drain. Do this around 3-4 times until the water isn’t so cloudy. If you buy highly polished rice one rinse or even no rinses will do just fine.

-

Put your drained rice in the pot you’ll be cooking in. Let it sit for 30-60 minutes.

-

Add 1 cup (plus a tad extra, I’d say a few tablespoons) of water to the pot as well. Cover it and bring to a boil, then turn it immediately to low heat. Let it cook for 10ish minutes.

-

Turn off the heat and let it stand (keep the lid on, this is important!) for another 15 minutes.

-

Open the lid and hope that you did it right. If you didn’t, go buy a rice cooker. Did I mention rice cookers are awesome?

That’s all there is to it. Rice is best served fresh. Second and third day rice isn’t all that great, though it makes for good chazuke (rice porridge). You may have to make adjustments to the timings above depending on your stove, though hopefully that does the trick for you. It worked okay for me, though I’m definitely just going to stick with the ol’ rice cooker.

Sauces

Although sauces are kind of not used in traditional shojin ryori, we’re going to include them here because hey, you’re probably not a Buddhist monk and neither am I. That being said, even if you do want to go 100% shojin ryori style, some of these are used in various dishes and not as a side dish (which is what shojin ryori tends to have problems with) so they’re still important.

When I went over shojin ryori ingredients, I made certain sauces (like ponzu) optional. Why? Because you ought to be making your own sauces. It’s so much better this way. Invest in some good shoyu, rice vinegar, miso, and mirin. If you do this, you’ll be able to make everything, and it will be amazing.

Nihaizu:

1 Part Rice Vinegar, 1 Part Shoyu

You’ve probably had this sauce before. Goes really well with gyoza and many other things. It’s also really easy to make! Just some vinegar and some shoyu in even amounts.

Sanbaizu:

1 Part Rice Vinegar, 1 Part Shoyu, 1 Part Mirin (or sugar)

Sanbaizu goes nicely with salads and is used to make other kinds of dressings. If you make it with sugar, warm everything up in a pan and let the sugar dissolve.

Ponzu:

1 Part Lemon, 1 Part Shoyu, 1 Part Mirin

Ponzu’s the best. I probably use it on too many different things. It’s great for dipping meats into (though we won’t talk about that here, ahem), though you can also dip various things from hot pots, shabu shabu, and so on into this delicious sauce. Trust me, making it fresh like this is totally worth it, too.

Amazu

1 Part Rice Vinegar, 1/3 Part Salt, 1.5 Part Sugar

The most complicated of the sauces! Put everything in a pot and let it simmer until the sugar is dissolved (don’t forget to mix!). Then, let it cool. Amazu can be used for marinating vegetables as well as for salad dressings.

And Now You’re Ready To Cook!

Next, lets take lot of these staples and apply them to some actual shojin ryori cooking! There are hundreds of recipes out there, though hopefully we will be able to put together something nice and simple to get you started. The goal will be to give you a better idea of the ingredients and staples that go into all of this, as well as provide for you a stepping stone that allows you to jump up to the “next level” so to speak. Shojin ryori is very difficult to get right, to say the least, so it’s good to take things slowly.

So, prepare yourselves! You're about to learn how to make the best vegetarian food you’ve ever had in your entire life!

First, I’m going to go over a couple recipes to get you started. These are things that I think are good, solid, all-around meals that you can do at home. After that, I’ll go over the things you need to know to get started yourself (so that you can cook any number of shojin ryori dishes!).

A Few Shojin Ryori Recipes

Although this is just a drop in the bucket in terms of what you could potentially be making, these are recipes that will get you started. Although I put these together with the idea that they’d make a nice “set,” the first two can be cooked on their own as an entire dinner. When you eat shojin ryori at a temple or restaurant, usually you get a ton of different little dishes. If you want to eat shojin ryori like you’re supposed to, though, you eat a main dish, a side dish, and some rice. This keeps things simple so you can concentrate on being a Buddhist monk, in theory.

Kenchinjiru (Kenchin Soup)

Kenchin Vegetable soup comes from Kenchoji Temple and is a great dish for the colder winter months. The interesting thing about this dish is the tofu, I think. It’s crumbled into the soup instead of cut into pieces. This came to be when a temple acolyte dropped a block of tofu, shattering it to pieces. Instead of wasting it (boo boo in shojin ryori), he cooked it with some vegetables and people seemed to like it (I bet he didn’t tell them he dropped it on the ground until after). Ever since then, this soup has been known as “Kenchinjiru” or “Kenchin Soup,” named after the temple it came from.

Ingredients:

- 4-6 dried shitake Mushrooms (fresh is okay too)

- 150g (5.5 oz) gobo (Burdock root)

- 2.5 cups water

- 300g (10.5 oz) daikon, peeled and cut to bite sized wedges.

- 1 block of konyaku, cut into bite sized pieces

- 200g (7 oz) carrots, peeled and cut into bite sized pieces

- 3-4 tablespoons sesame oil

- 100g lotus root (3.5 oz), peeled and cut to bite sized pieces.

- 2 tablespoons shoyu (soy sauce) for sautéing

- 2.5 cups kombu stock

- 4 tablespoons saké

- 1 block firm tofu

- 4 tablespoons shoyu (soy sauce) for soup

- 2 tablespoons red miso (or 3-4 tablespoons white miso), optional but recommended!

- 100g of greens (i.e. baby spinach, collared greens, etc)

- Small amount of ginger juice

There are a lot of ingredients here, but the important thing to know is that you can substitute many of them. Kenchinjiru is typically a soup you make with leftovers, meaning you can do nearly any kind of vegetable. This also means that the amount of vegetables doesn’t have to be exact, either. Experiment and play around with it, adding more of the vegetables you enjoy most!

Recipe:

-

Soak the shitake in the water for 10 minutes. Drain. Soak for another 30 minutes in the 2.5 cups of water. Remove the mushrooms but keep the water as you will use it later. Remove the stalk and cut into thinnish bite-sized slices.

-

Peel the gobo and cut into thin bite-sized slices. Soak them in cold water for 5 minutes to remove bitterness. Drain and put aside.

-

Cut the daikon into bite sized pieces and soak in cold water for 10 minutes to remove bitterness.

-

Cut the konyaku into bite sized pieces and boil for a couple of minutes. Drain and remove.

-

Heat up the sesame oil in your soup pot (or in a separate pan) and stir fry the gobo, shitake, konyaku, daikon, carrot, lotus root, and shoyu (2 Tb) for around five minutes.

-

Add the shitake water, kombu stock, and sake. Bring to a boil. Cook on low heat until vegetables are tender (30-45 minutes). If there’s any scum / froth forming on the top, remove it with a spoon.

-

Crumble the tofu block into the pot and mix it in. Add the 4Tb of shoyu and 2Tb of miso. Stir gently for a while until you think the miso is dissolved.

-

Add your greens and cook them lightly. Add a small amount of ginger juice to taste.

When you serve this, you can add a little more shoyu to individual bowls as well (to taste) depending on how addicted to salt you are. This soup is great served fresh and gathers more taste over time. Goes really well with a side of freshly cooked rice.

Vegetable Tempura

This recipe’s a bit tougher. It’s one thing to make tempura using egg. It’s another to make it without egg, and that’s exactly what you have to do with shojin ryori. If you get it right, I think it tastes much better. In fact, you shouldn’t need any sauce to dip it in (shojin ryori isn’t too into sauces).

Ingredients:

The great thing about vegetable tempura is that you can tempura just about anything, so long as it’s fairly solid. What you use is really up to you. Here are some examples to get you started:

- Kabocha, cut into thin slices

- Carrots, cut into thin slices

- Fresh shitake caps

- Brocolli

- Sweet potatoes, thinly sliced

- Wherever your imagination takes you!

No matter what you choose, though, you’re going to need some stock ingredients to actually cook these vegetables with:

- 1 cup cake flour

- 1 pinch baking soda

- 1 pinch of salt (optional)

- 1 cup ice water

Recipe:

You’re going to want to take the three above ingredients and mix them together. Don’t overmix it – some lumps are okay. This concoction shouldn’t be too thick, otherwise there will be too much batter on your vegetables (should be thin and see-through when you apply it).

Heat up some oil to 170-180 degrees. Oil should cover the bottom of the pan (or, if you have a deep fryer you can probably use that). Dip the vegetables in the batter, lightly covering. You should be able to see through the batter easily. If you want to be fancy, green colored things look good with only partial batter, leaving some green showing. Fry both sides until it looks cooked (lightish brown), remove, and put on some paper towels. Pat the oil off.

Tempura is best served right after it’s finished, so serve right away!

Ringo Umeboshi Ae

Mmmm. Time for dessert! If you’re lucky enough to have picked up some umeboshi off the shojin ryori ingredients list, then lucky you! You can probably make this. Feel free to double the recipe if you want more. You’ll need:

Ingredients:

- 1 medium apple (how about Fuji?)

- 4 large umeboshi

- 2-3Tbs of sugar

- 1 tsp Mirin

The tricky part about this recipe is the umeboshi, though. Umeboshi vary in terms of how sour they are. If you have a very sour umeboshi, poke some holes in them and let them soak in water for a few hours. Alternatively, you can add some more sugar. It may take some playing around and experimentation to get this recipe right depending on your personal taste preferences and the umeboshi you have gotten. Here’s the standard recipe, though.

Recipe:

-

Cut and peel the apple, then cut into bite sized pieces.

-

Rinse the apple in lightly salted water. This will help the apples keep looking youthful and fresh. Blot dry with a paper towel (we don’t really want to add extra saltiness, here).

-

Remove the umeboshi pits and turn the rest of the umeboshi inside out. Add sugar and mirin, then heat on low until things are nicely blended together. Let it cool a bit.

-

Mix the umeboshi sauce with the apple slices to serve. Yum!

This is a pretty standard style shojin ryori dessert experience. You won’t see any cake (it’s a lie, after all) or anything overly sweet. Desserts usually consist of something fairly mild, or even sour (like umeboshi!). Fruits are great for this, and you’ll see apples served as dessert quite often.

Bonus: Take some hot water (180 degrees Fahrenheit) and squeeze some ginger juice into it to make ginger tea. It’s a nice compliment to this dessert. You can also use ginger shavings from the ginger you used with the Kenchinjiru.

So How Was A Month Of Shojin Ryori?

I gotta say. Cooking shojin ryori style is a lot of hard work. There’s a lot of ingredients and they take a lot of tender loving care. You’ll be spending a lot of time running back and forth from pantry to cutting board to stove to recipe book, frantically putting things together while everyone patiently waits for dinner. In fact, the term “gochisou sama deshita,” which you say after a meal in Japan to express your thanks for it, literally means “running around.” Why? Because this is exactly what you have to do when you are making a shojin meal. Experience goes a long way, here. I found that as I was able to manage more tasks and focus my care on the food, the food got better as well. I’m sure I still have a long ways to go. Just be sure to not give up after the first try. It takes a while.

Besides the actual experience of cooking, eating nothing but shojin ryori food for breakfast and dinner (I just ate vegetarian regular food for lunch) had its health benefits as well. Although I didn’t keep track of weight or anything, I’m definitely a little less chubs, all while ignoring calories, because numbers, eugh. I don’t have any experience with dieting, but this seems like a really healthy and steady way to shed some pounds. Do this for a year and you’ll be feeling pretty damn good, I think.

I definitely found that after two or three weeks I felt better as well. Things like miso, seaweed, and root vegetables are just so great for you. I have more energy and I feel more concentrated. Oh, and did I mention my hipster jeans fit better? So good for squatting down to take pictures with a Holga Polaroid.

All that being said, do I recommend it? It’s definitely not an easy lifestyle choice to carry through with. It’s a lot of work and the food isn’t going to taste good for a while (until you get better at this kind of cooking). It’s just hard work, and although I’m a huge fan of this type of food I also wish I could chain a Buddhist monk to my kitchen to cook all this for me. That being said, you get faster with time and it’s not all that bad. If I had to go back and do it again I definitely would. Also, going forward I’m going to keep making shojin ryori food and stay vegetarian 6 days a week, or so. It just comes down to how much healthier I feel now that this month is over.

Getting Started With Shojin Ryori

So now you’re convinced. You want to put yourself through the trials and tribulations that are shojin ryori. Okay! I can help you get started. These are the books that I used (especially the first two). They’ll keep you busy for a long time and get you easily through your first month of cooking.

The Enlightened Kitchen

This was actually the book that got me interested in this idea. I came across it in the bookstore and leafed through it. It made me remember all the awesome shojin ryori food I had had in the past and made me realize that I could make some of this food myself! It’s written by a lady who’s married to a shojin chef in Japan and has a mix of traditional and modern. It’s a great getting-started book because it caters to the Western reader without jumping the shark. If you only buy one book I’d recommend this one, though after a month or two you’ll be craving for more, I think.

Shojin Cooking

This book is a bit old and was written by Keizo Kobayashi, someone who went around gathering recipes from various Buddhist monks and temples. I like this book a lot because it’s no frills and very simple. Sometimes it’s too simple, though, not giving enough information for a newb like me to cook the dish properly the first time. That being said, I’ve always been able to figure things out though, and the things I learn during that process have been invaluable. This book is full of traditional recipes. If you’re planning to be very diligent about this point, “Shojin Cooking” is your kind of book. Still, I’d recommend learning the basics from Fujii’s book (above) before diving into this one for a better overall experience.

Kansha

Kansha is written by Elizabeth Andoh, who also wrote Washoku (a similar Japanese cookbook that includes meat-things). Kansha is all vegetarian though it doesn’t necessarily focus on shojin ryori, though it never claims to do so. It does, however, have plenty of shojin ryori recipes, not to mention many other vegetarian recipes as well (almost as good, right?). What I like about Kansha is that it doesn’t get too fancy. It stays pretty simple and traditional most of the time, the food is good, and it has a lot of pictures and recipes. I haven’t had time to go through this book as thoroughly as the first two, though I’m excited to try out many of the recipes in here. I’d recommend this as your third book should you exhaust the first two, though it is very good.

Nobu’s Vegetarian Cookbook

Last is Nobu’s Vegetarian cookbook. Nobu’s sort of a big-time chef, and I think that shows in the cookbook. Many of the recipes are too fancy for my taste, though there are plenty of gems in here as well. I learned a lot about the science behind Japanese vegetarian cooking which gained me a deeper understanding of how everything goes together (which has helped tremendously). I’ve also done a couple recipes out of this book and they’ve turned out nicely. Although I’m not really into the fancy “modern” vegetarian cuisine in this book I have found it useful. I’d recommend it as the fourth book in your collection of Japanese vegetarian cook books.

So there you have it! A month (plus a little) of shojin ryori experience down on paper for you all to read. I’m not particularly good at this whole shojin ryori thing yet, but I do hope to get better. If I can’t live in a temple on Mt. Koya, this is the second best thing, though it’s a very, very far second.