Coffee! The fuel we consume to get our day started (or keep it going). For some, coffee is a quasi-religion. Many parts of the world enjoy and make a living off of coffee.

But how many coffee beans need to sacrifice their lives in order to appease us, their drowsy, crabby, overlords? Turns out that number comes out to nearly 2.5 billions cups of joe, per day. That’s about 40% of the world population, assuming that only one person drinks one cup (like that’d happen)! To further put it into perspective, coffee is the 2nd most traded commodity in the world, putting it right behind crude oil. The industry itself is valued to be 70 billion dollars. So where does Japan fit in all of this?

If you’ve ever looked at Japan’s Starbucks menu or used gamu shiroppu, you know about Japan’s spin on seasonal flavors and efficient service. Beyond unique Japanese flavors, though, some coffee shop adaptations naturally attract certain consumers. Looking at these different traits, along with the evolution of coffee-drinking in Japan, illuminates a new side of a culture Tofugu readers like you love. So I’ve put Japanese cafés under a microscope (not literally, obviously – Japan’s tiny spaces aren’t that tiny) and, based on readings and personal exploration, found some things you might want to know.

Kissaten Origins

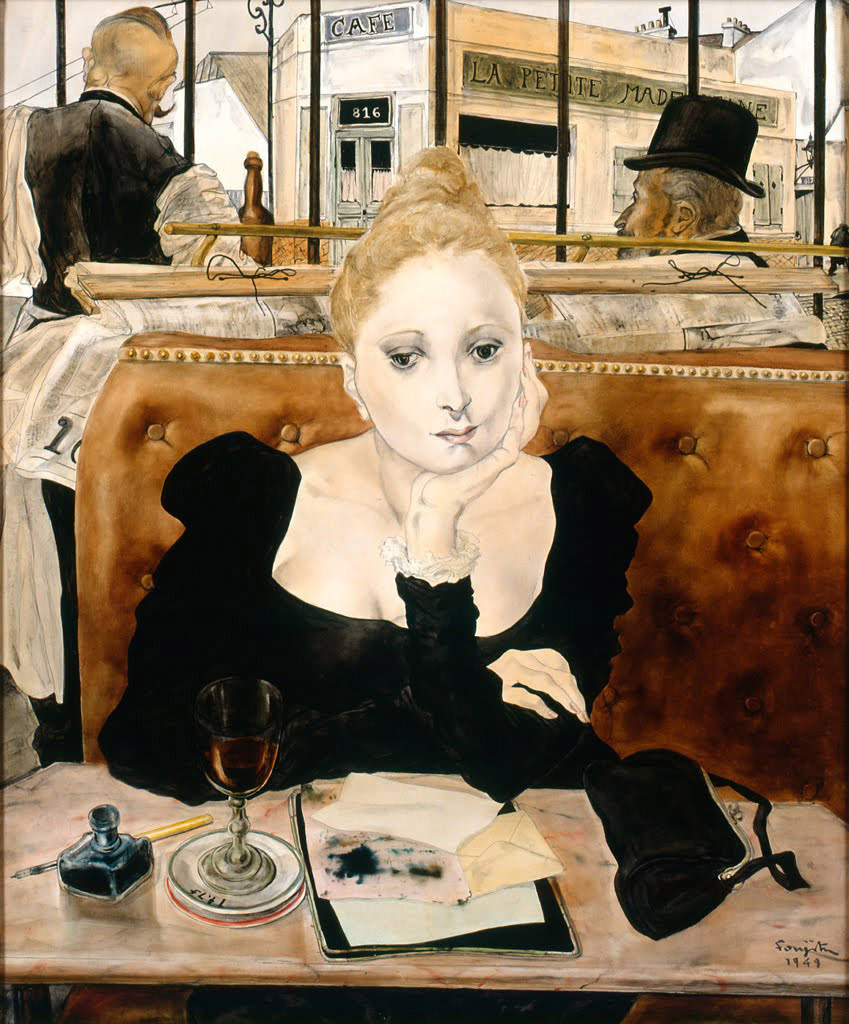

Coffee was originally introduced to Japan via Dutch Trading Ships in the 1800s. But it wouldn't have gone anywhere without he original Japanese coffee shop, called a kissaten 喫茶店. My own kanji-by-kanji interpretation of the word is whacky and off-point, “caffeine savor store”, while the more sensible Makiko Itoh says that it literally means “tea tasting shop.” She describes it as a no-rush place to grab a bite and something to drink. The word is more loosely translated as “coffee lounge”, which suggests a languid, dreamy atmosphere. Considering kissaten were the habitats of such creative creatures as Léonard Tsuguhara Foujita (artist), Junichiro Tanizaki (writer), and Yoko Isaka (poet), “coffee lounge” is probably the most accurate interpretation.

Before the kissaten, there were chaya – traditional tea-serving joints. Chaya 茶屋 had been the pub-like nests of camaraderie, gossip, and familiarity in villages and along the old roads. In other words, chaya were physical twitter feeds for pre-Meiji Japan. In a chaya, one was known and menu items were cheap and small. Kissaten, on the other hand, didn’t sell green tea or dango, but focused on coffee or black tea, and, from the very first establishment, provided tobacco and newspapers, all in a setting modeled with モダン (“modern”) furnishings – Western tablesets, bars, and Art Deco.

Merry White, author of Coffee Life in Japan, writes, “At different times in the past 120 years the Japanese café has offered more than coffee … and private solace, [but], depending on the era… cafés have provided what the city dweller needs” (30).

The first time such a place existed in Japan was 1888. A man named Tei Eikei, who was the well-traveled, multilingual, adopted son of “a Taiwanese secretary in the Japan Foreign Ministry” (White 18), established the first Japanese kissaten. He named it Kahiichakan, and it went bankrupt in five years.

That short-lived but influential first kissaten gave birth to the trend of coffee-central drink halls.

It was Meiji-era Tokyo, where industrialization was affecting more than just technology. Class structures like “samurai” and “merchant” and “emperor” were breaking down. Men and women were increasingly moving towards urban centers and taking on 9-5 jobs or pursuing education. Naturally, kissaten blossomed along the train lines, acting as information hubs for those who were new to the city and as locations for businessmen to play Angry Birds until their next train.

Despite the importance of these original cafés, I never heard this word spoken in Japan; ‘Kissaten’ is a term I learned formally. A friend of mine suggests that it’s an older-sounding word, one that brings to mind a certain style of place (like Chatei Hatou) and sells ナポリタン (Naporitan) in addition to the standard coffee or black tea.

For him, a twenty-something year old, there’s a better word for a place that sells coffee. That word is kafe カフェ.

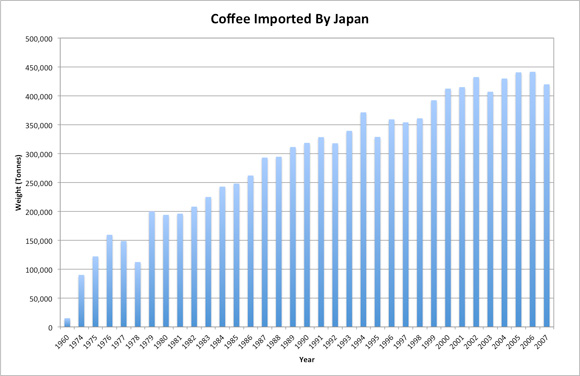

Though coffee enjoyed a lively start with the kissaten in the Meiji period, it didn’t start booming until the 1960s. Shortly after the import suspension ended in 1949, coffee started to trickle back into the Japanese market. Japan imports more than 440,000 tonnes of coffee annually. Back in 1960, the yearly import was 15,000 tonnes. Quite a huge difference, wouldn’t you say? A 3000% increase in only 50 years.

What is responsible for the coffee boom? It’s a combination of many things, but it can be boiled down to Japanese interest in everything Western (especially after World War II), and large investments in marketing and R&D.

The first breakthrough for coffee came in 1965, when Japan released the world’s first kanko-hi- かんコーヒー (canned coffee) called Mira Coffee. Unfortunately, it wasn’t much of a success as the hype cooled down shortly after. Four years later, UCC Ueshima Coffee Co., who is often credited for pioneering canned coffee, released their product to the masses and the rest is history.

Although the concept of canned coffee was a success, it alone was not responsible for the bean's rise to prominence. In 1973, the hot and cold beverage vending machine was introduced in Japan. Coupled with the 100 yen coin that began circulation in 1967, vending machines and subsequently canned coffee became a huge hit. Ready-to-drink (RTD) products were just part of the equation for the rise of coffee.

On a different part of the spectrum, Japanese coffee houses and chains also began to emerge in great numbers. Doutor Coffee chain opened their first store in 1980 and established the coffee culture in Japan. Recovering from World War II, the Japanese spent great lengths to recover their economy. With their perseverance and hard work attitude, grabbing a meal and drink on the go for the long commute to work or the late-night working sessions was becoming a more common sight. Doutor Coffee anticipated this. In response, they modeled their business for the on-the-go working Japanese. This has been a successful model that many associated with coffee until the mid 1990s, when Starbucks entered the marketplace with their friendly, casual “third place” model.

Chain Mutations

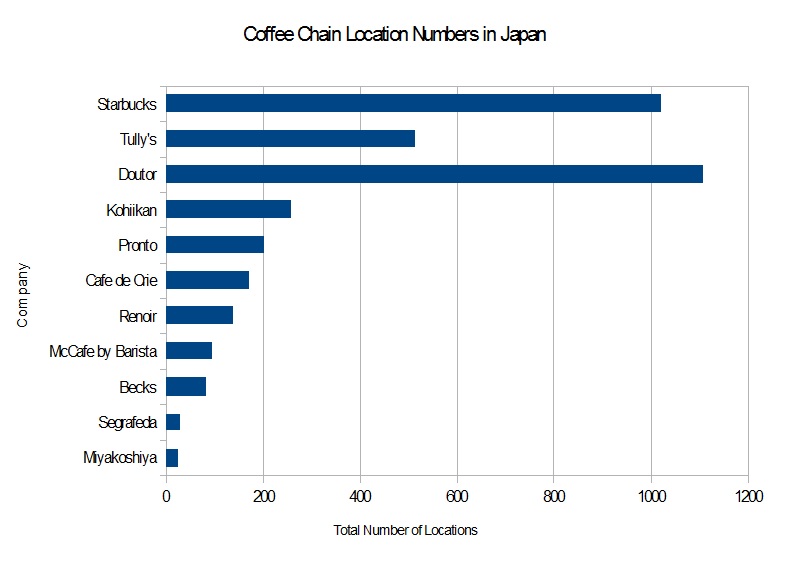

Doutor, established in 1980, is the biggest such beast in the land. It’s similar to other large coffee companies, like Pronto, for diversifying its store brands. When I say diversify, I mean going up and down the scale of price, variety, and location. For example, the train stop Doutor breed often has cheap food and little variety, while the Ecelsior Café is a happy medium of price, taste, and convenience. Still higher up the ladder and out in suburban areas is Café Colorado. Higher still in price, and in ritzier metro areas, is Le Café Doutor. Check out the graph below for an idea of numbers. I made it after counting results from each company’s ‘store locator’ section on the official websites.

Another trait that both large and small cafés share in many cases is smoking. Segrafeda, a popular Italian-style chain, is notorious for its smoky haze. Tully’s, a popular foreign company, and Doutor also have seem to have vague or non-existent separation for smoking in-store. Some Japanese, often older folks, appreciate the pairing of coffee and tobacco. But plenty don’t – a trend that has helped the success of those establishments which are non-smoking. In this survey by Nifty, 40% of men and 53% of women respondents would like to see cafés become non-smoking areas. More then half said that when choosing a restaurant they would look exclusively for non-smoking places.

Smaller chains usually optimize one trait or focus one one locale to compete. Renoir isn’t so small, but flocks around Kanto and is known for prioritizing plug-in and wireless access for patrons. Then there is Miyakoshiya, which only has 26 locations but thrives by crowding up Sapporo. This mostly-Hokkaido chain also maintains a good reputation for both quality coffee and responsible smoking/non-smoking separation.

Finally, there is the most recent coffeeveelution of kissaten: independent cafés and espresso bars. The total number of cafés, from chain to independent, has been shrinking. But White suggests this decline isn’t a result of endangered mom-pop stores, but rather an effect of the Bubble Economy. After Japan’s recession, a downsizing had to happen. White adds:

“[T]his does not signify fewer customers for cafés or a growing use of chain coffee shops like Doutor or Starbucks (whose appearance simply created a new customer base rather than poaching on that of the independent cafés)” (White 38)

Some people still paint the picture as dismal, though, convinced that the success of foreign competitors like Starbucks is threatening the livelihood of local coffee masters.

How Much Coffee Does Japan Drink?

Japan only ranks as the 39th largest consumption per capita for coffee, tallying in at 3.2 kg per individual. However, they are the 3rd largest importer of coffee, sitting behind the United States (1st) with 4.23 kg per capita and Germany (2nd) with 6.93 kg per capita. Working out the numbers, Japan imports over 440,000 tonnes of coffee annually. This means they import about 7% of the world’s annual coffee exports. So what is a country where tea is the more common mainstay brew doing with a product that is common in the West and Near East? Is it to fill all those coffee bean sniffing cups for all of their insane department stores’ fragrance floors? Nope. Like a KFC Christmas, it is the result of fifty years of clever marketing and Western influence that helped coffee become the go-to-brew for the Japanese.

Brazilian coffee-growers deliberately, and successfully, reached out to Japan in the late 1800s to export the original energy drink. From then on, expatriates working at the top of the industry, combined with the burgeoning crop of cafés in Japan, made the daily cup of joe as Japanese as wasei-eigo. More than a century later, Brazil is still the largest supplier of unroasted and instant coffee to Japan, which now ranks third in global coffee imports for consumption.

Thanks to those coffee relations, the Japanese map features home-grown cafés blazing beyond the original kissaten species. The first café chain in the world, for example, Paulista, was established in Japan in 1908. Fast forward past the sad war times when coffee (and everything else) was hard to come by and up to when Japan started getting on its feet economically: coffee chains became a big thing. After all, busy salarymen and OL’s needed their caffeine. Not too much has changed in that regard.

Coffee Products in Japan Today

The Japanese Coffee market is a very competitive, saturated market. A few of the popular Japanese canned coffee brands are Boss (produced by Suntory), Georgia (produced by Coca-Cola), Nescafe (produced by Nestlé), and Roots (produced by Japan Tobacco). Quite a diverse group of producers we have here, wouldn’t you say? Liquor, soft drink, food, and cigarette companies all making canned coffee. Some of the aforementioned popular coffee shops are Doutor and Starbucks. Starbucks entered the Japanese canned coffee market in 2005, partnering up with Boss’ producer, Suntory. Fast food joints are also joining the fray. McDonalds, not wanting to be left out, launched their own chain of coffee store fronts, McCafés, across Japan a few years back.

As with anything Japanese, coffee isn’t exempt from their weirdly fascinating marketing. Take for example Boss coffee. In 2006, the company hired Tommy Lee Jones to be their spokesman. Since then, he has appeared in many commercials as character “Alien Jones” who was sent to Earth to examine the human society. Roots Coffee also has their own celebrity spokespersons (Ewan MacGregor and Brad Pitt), however they aren’t on the same level as Tommy Lee Jones. Here are a couple commercials for your viewing pleasure:

Who watched all nine minutes of these BOSS commercials? *Raises hand*

Foreign Franchises

The three biggest foreign coffee-providers in Japan are Starbucks, Tully’s, and, believe it or not, McDonald’s.

While any one of the more than 3,000 McDonald’s stores in Japan will sell a cup of coffee, the corporation began establishing standalone coffee shops in 2007. These coffee shops, so far 94 in number, are called Mccafé by Barista. They provide typical café sandwiches and sweets but specialize in a higher grade coffee than the normal McDonald’s. The menu is also pricier than the regular McD’s, but still less expensive than Starbucks. Mccafé by Barista’s real battleaxe, though, is its high number of 24 hour locations (84 of 94 total) and the increasing number of delivery service cafés (14 of 94 total).

Invading species No. 2 is Seattle-based Tully’s, which opened its first Japanese branch in 1997. Now, 513 Tully’s dot the island country. Taking a look at some of the menu items, Tully’s seems to be a bit more like the traditional kissaten in offering things like pasta. Yet, you can also order ice cream, which sets Tully’s apart from most other coffee shops I’ve been to, though maybe ice-cream selling cafés are a thing in Japan. Price-wise, it’s about the same as Starbucks.

That brings me to the only chain with numbers comparable to Doutor: Starbucks. More than 1000 branches have been established in Japan, though naturally these cluster around metropolitan areas. Starbucks opened its first Japanese branch in 1996 in Ginza, Tokyo, and quickly gained footing in the Japanese coffee-service market. A 2006 survey by MyVoice demonstrates how connected Starbucks became to local consumers in just ten years: for those respondents, Starbucks was the most loved and most often visited self-service coffee shop. That’s enough to convince me it’s not foreign anymore – Starbucks adapted with its new surroundings and fit them perfectly. Though, not everyone feels that way, as you’ll see below.

Tottori Invasion

Last year, Tully’s announced plans to open a location in Tottori Prefecture, a small place where the largest city has a population of about 200,000. Tottori is notable for its unique sand dune tourist destination. Tottori is also notable because until this year, there was neither a Tully’s nor a Starbucks in the prefecture. Not long after Tully’s announced their move, Starbucks matched suit, releasing its own plans to set up shop in sand-dune-land. This shouldn’t be noteworthy except that these are foreign-grown companies. Doutor actually doesn’t have branches in Shimane or Oita, but no one seems to be fussing over that. (Maybe Shimane and Oita are happy with the Starbucks or whatever there)

We asked some residents of Tottori how they felt about the encroaching Starbucks:

“It’s sad that, since there aren’t any Starbucks in Tottori, I don’t have any places to read or study with a nice coffee by myself. If it was built, my guess is that quite a lot of people would go.” -Shokotan, 28-year-old woman

“It’s fine that we don’t have any Starbucks. I mean, if there was one, I might go, but I’m not bothered that there isn’t one. Actually, there are cafés that originate in Tottori such as ラバール (La Bar) because we don’t have Starbucks. So I think not having Starbucks makes Tottori create new businesses.” –Masashi, 25-years-old man

“I’m actually disappointed to hear that Starbucks will be built in Tottori. Like the Tottori governor said,”We don’t have SUTABA (Starbucks), but we’ve got SUNABA (sands) in Tottori” – it’s part of our charm.” –Anonymous 20-something

The whole thing has made a bit of a stir on Twitter and in the news. I even found this small talk-radio style video with an older host who is utterly confounded by Starbucks in a Lewis-Black angry kind of way.

He’s a smoker (“First of all, you can’t smoke in there”) who criticizes the menu (“What the heck is with this menu?…There’s too much…… The heck’s a ‘Furappaccino’?”) and the use of lids (because then the drink takes forever to cool down and he burns his tongue).

Successful Transmutations

Except for the smoking, I’m on that talk-show guy’s side. His strong opinion goes to show that despite Starbucks’ popularity, there are true fans of older-style chains and kissaten. When you consider the other voices from Tottori (including two other people in that video) that are either ambivalent or fond of Starbucks-esque cafés, you can see the range of adaptations different companies have made to survive since Kahiichakan.

Have you tried Naporitan or the Sakura Macchiato? Tell me about your Japanese café experiences or, for those who haven’t been yet, your aspirations. And if you’re in Tokyo looking for a neat place to get caffeinated, check out our travel guide for Omotesando Coffee.